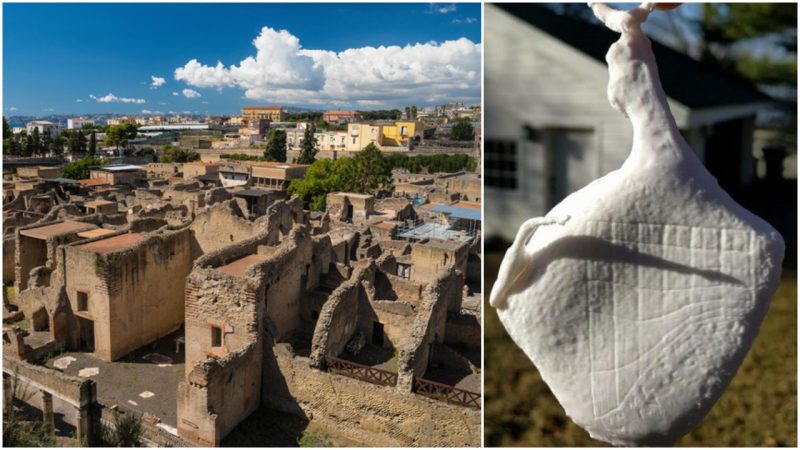

It was a man by the name of Emmanuel Maurice that first stumbled upon the ruins of the city of Herculaneum. The ancient Roman city had slept undisturbed for almost 700 years, buried underneath a 60-feet-deep blanket of rock –solidified lava, mud, and ash which had burst from Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D.

“At last the men’s picks struck on metal, making it ring like a bell,” writes C. W. Ceram in his book Gods, Graves & Scholars. “The first find consisted of three fragments of bronze equestrian statues sculptured on a heroic scale.” But that was just the beginning of Maurice’s discoveries.

It was December 11, 1738, when “an inscription was found indicating that a certain Rufus had built, with the money of his own, the Theatrum Herculanense.”

It was this very description that gave a name to the long-lost ruins. The statues that they uncovered were the first in the line of many surprises that this city had in store, wonders that awed the world.

It wasn’t until the 1760s that a somewhat unusual artifact was unearthed at the site of a once-grand villa. Truly, the archaeologists that worked at this site were amazed by the finds on a daily basis, but this object was quite different.

For starters, it held a strong resemblance to a pork leg. The shape of it was too strange to go unnoticed.

After much thought and investigating, it was discovered that the strange artifact was a form of ancient clock. In fact, modern researchers suggest the the small metal sundial, dubbed the “pork clock,” was akin to a pocket watch.

When Vesuvius literally blew itself up to pieces, Herculaneum was right in the path of the pyroclastic flow. This incredibly fast-moving wave of hot gas, boiling mud and fragments of rock swept through the city, swallowing up the buildings, the people, and the answers that might aid scholars in their quest to unravel this mystery.

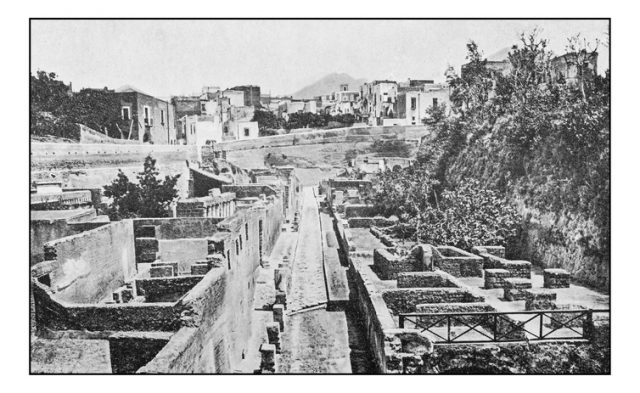

Given the fact that this is a unique find, researchers figured making a replica of it was a must. This is where the benefits of today’s technologies come in handy.

A 3D printer was used to recreate what National Geographic describes as a “lump of metal small enough to fit in a coffee mug.” And so a new, white, 3D model was born, one that could easily be handled without fear of damaging an irreplaceable object. It took quite a bit of practice to perfect the art of telling the time using the ham-shaped watch.

7 Things you may not know about Roman Gladiators.

There is a grid of lines of one side that represent the hour and month; the vertical lines are for the months and the horizontal for hours.

And just like in a typical sundial, a shadow is cast upon these lines and thus the time is revealed. The real mastery, however, was to tell the time on windy days.

3-D print by Christopher Chenier. Wesleyan University.

Christopher Parslow from Wesleyan University explained to the Daily Mail that the portable sundial is hung from a string and that “with a bit of practice, he could read off the hour easily – although he admitted it does sway in the wind more than he expected.”

The original artifact was missing it’s gnomon, or the stick-part that casts the shadow, so the team created one as described by Maurice’s 18th century records — in the shape of a pig’s tail. The original has lost this feature at some time during it’s storage. How to tell the time with this curious clock has been solved, but what continues to evade archaeologists and scholars alike is the shape of the artifact. Some even argue that it is styled in the shape of an ancient water container.

But that doesn’t explain the pig tail. According to National Geographic, “the pig is a symbol in Epicurean philosophy, which emphasized living for the day.” Is this an ancient form of humor? Or maybe the shape serves an unknown purpose. Researchers are still working to unravel the mystery of the pork sundial.