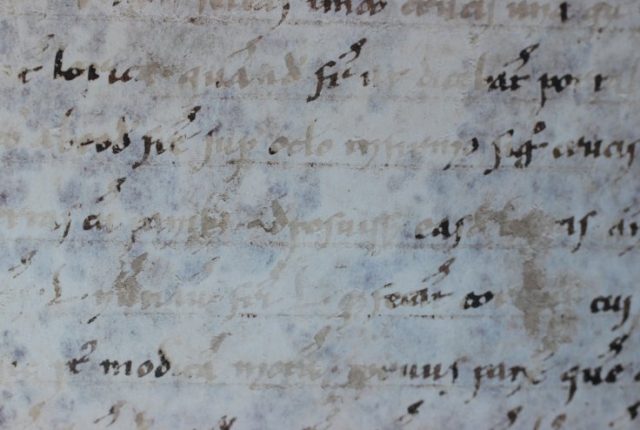

For a long time, historians, archivists, and other researchers have been irritated and embittered by purple dots which are known to obscure the contents of old manuscripts dated to medieval times.

The invading dots have been persistent. They would appear on Middle Age documents from different regions in the world. The discoloration even showed up on a carefully stored 13th-century scroll which was kept under optimal air and light conditions at the quarters of the Vatican Secret Archives.

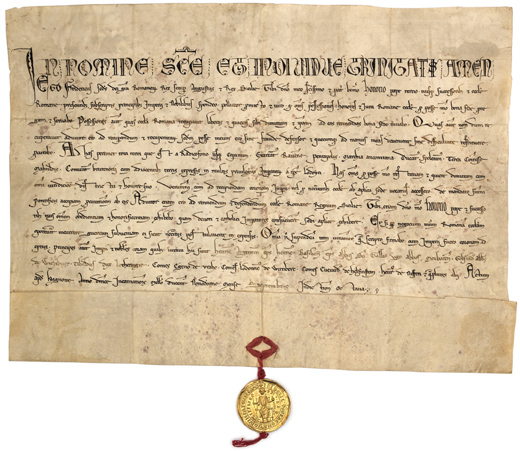

The scroll is dated to 1244 and tells the story of Laurentius Loricatus. The piece measures 16 feet in length and is the group effort of villagers in Italy asking the Pope to induct a man called Loricatus as a saint. On the same scroll, experts have detected the remnants of a salt-hungry bacteria.

The research results were published on September 7, 2017, in the journal Scientific Reports. The findings explain how the striking purple pigment has been made by salt-loving marine microbes.

The effort was led by Dr. Luciana Migliore from the University of Rome Tor Vergata. Ecotoxicologist Dr. Migliore couldn’t quite believe at first that marine bacteria was the culprit.

“When my students came to me, saying, ‘Luciana, we found marine bacteria,’ I told them, ‘Repeat, please; there is a mistake. There must be a mistake,’” Dr. Migliore shared in an interview for Fox News.

The parchment, made of goatskin, had been resting in the Vatican Secret Archives for three centuries and it first arrived at the Vatican shortly after its creation in a village close to Rome. It’s unlikely the piece ‘vacationed’ by the sea during its eight-centuries-long existence.

However, the lab results attested to the presence of marine bacteria. That was the reason why the margins of the parchments were damaged, as well as its first and final pages, making the Loricatus story an incomplete read.

After it was considered how these parchments were made in medieval times, the finding made more sense.

Different skins of animals were used to produce writing parchments; commonly goatskin, also cowskin and sheepskin.

Once the hide was removed from the animal, each piece of skin was treated with sea-salt. This step was aimed to clean any flesh-eating bacteria from the skin, preserving it for long-term use.

What our ancestors couldn’t have foreseen was that the same process encouraged a different biodeterioration process. The skin still retained some trace of salinity, just enough to allow salt-loving aquatic bacteria to develop its own colonies.

The lab tests also revealed the presence of different bacteria. Which means, once the salt-loving bacteria colonies died, another type of bacteria appeared, these feeding from the remnants of the former colonies.

There was an entire chain of bacterial life that was responsible for the odd purple pigmentation. Bacteria concentration was lower on areas of the parchment that remained untainted by the colored pigment.

World famous landmarks that are hiding something from the public

The 13th-century parchment which the Italian university used for pursuing this research has an intriguing story on its own, needless to say.

In the spotlight of the document is Laurentius Loricatus, a young Roman soldier around the year 1205 who unintentionally became a murderer. It happened that he took the life of an innocent man.

The horrid event prompted Laurentius Loricatus to embark on a pilgrimage journey and a 34-year-long life of rigid austerity. He would spend his hermit years in a remote monastery in Santiago de Compostela, in the Spanish region of Galicia. Laurentius became a Benedictine monk, following the steps of Saint Loricatus of the 11th century A.D.

His culpability made him severely self-punish himself. Similarly to the 11th-century saint, Laurentius fulfilled his penance by wearing chain mail, which is why he was the designation Loricatus was added to his name.

Besides his story of painful penance, Laurentius left a book of prayers to the people who commended his life journey. His death occurred in 1243, and a year later the vellum parchment asking the Pope that Laurentius is pronounced a saint made its way to the Vatican.

A few centuries passed until the Vatican processed this request, but finally in 1778, under Pope Pius VI, Laurentius was honored. Currently, he is known as “Blessed Laurence Loricatus” and his day is observed each August 16th.

By an odd chance, the goatskin parchment which demanded the Pope to do all of this, also helped experts understand more about the nature of the frustrating purple discoloration.

Dr. Migliore with her team is confident their discovery can now help other documents threatened by the Halobacteria, perhaps even helping their restoration process.