An ill-fated chain of events unfolded in the summer of 1922 when the name of a distinguished hotel in the Scottish Highlands became associated with the worst case of botulism to occur in the United Kingdom.

The Loch Maree Hotel, overlooking the shores of Loch Maree, was well known among vacation-goers and admirers of nature. On Monday, August 14th that year, a group of 32 people gathered to fish trout together: 13 hotel guests plus ghillies and boatmen to assist them.

The staff at the hotel provided them with nicely packed lunches for the day. As the group settled down for a lunch break, nobody suspected that the food might be tainted and that a few days from now, eight of them would die from food poisoning.

Some of the people who ate the hotel food fell sick quickly. By the evening they were already complaining of pain, with some experiencing an issue with their eyes and double vision.

Everyone, including local doctors who came to check on the sick, was baffled at the unusual combination of symptoms. But the real shock followed when people started dying.

Was this a successful mass murder attempt, done on purpose? Nobody was clear at first. The police were called to investigate.

The entire Loch Maree Hotel was searched for clues and its owner, Alexander Robertson, interrogated. Neither he nor the cook had any idea what led to the eight deaths.

One expert physician who was sent from Glasgow eventually proposed that the tragedy was due to food poisoning.

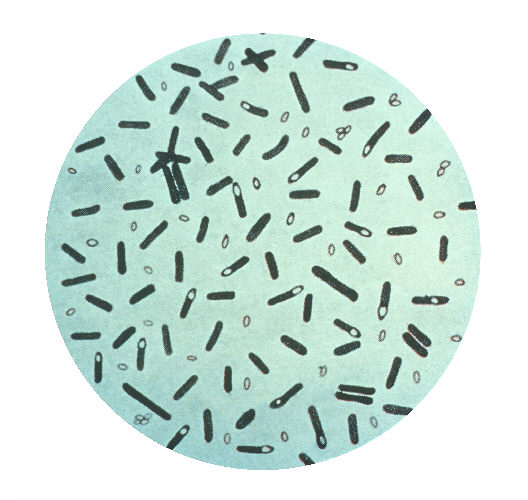

The inquiry continued. Investigators even looked for an answer in the hotel’s garbage, where the remains from the picnic that day were disposed of by the hotel staff. Although the retrieved samples were small, analysis eventually revealed the traces of a deadly Bacillus botulinus.

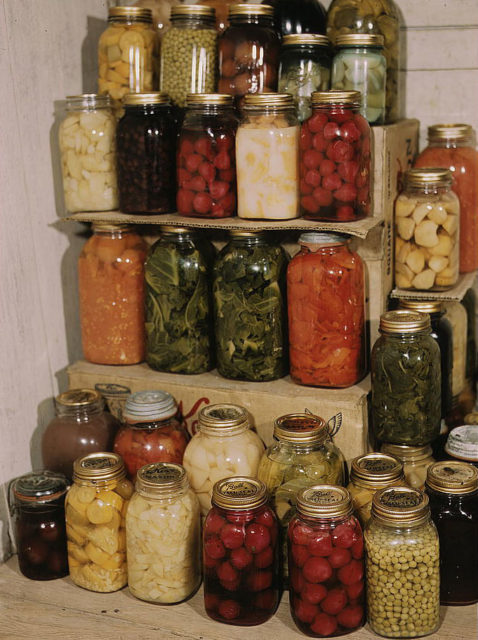

The bacteria was found in a jar of canned duck pate. The eight people who died after the fishing trip had all eaten a duck pate sandwich. Others in the party had eaten the same, but only one jar was infected.

While poisoning from the botulinum toxin, which is produced by the bacteria, was known to mankind long before 1922, it was not so familiar to Scotland.

The first recorded cases of botulism appeared as early as the 18th century, in Germany. The poisoning was linked with the increased production and consumption of sausages. The disease was even named from the Latin word meaning sausage — botulus.

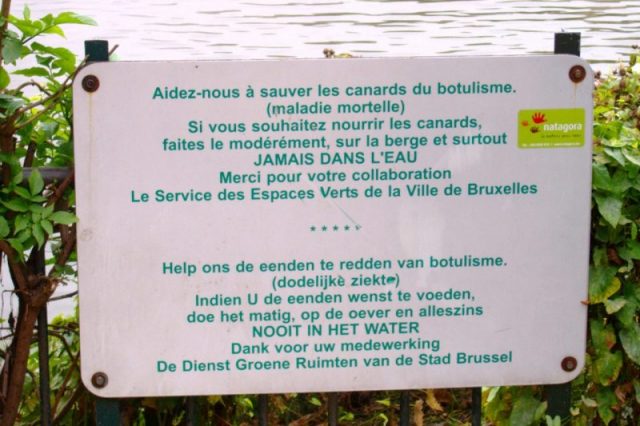

Another severe outbreak occurred in a small Belgian village called Ellezelles, where there were multiple casualties in 1895. It was during this outbreak that the pathogen was first isolated, by Belgian bacteriologist Émile van Ermengem, in a home cured ham. Its scientific name was later changed to Clostridium botulinum following further detailed studies of the bacterium.

Clostridium botulinum is an anaerobic bacteria, meaning it grows only in conditions where oxygen is excluded, and it’s spores are resistant to high temperatures. The environment produced by the canning process is perfect for this microbe to thrive if the jars are not heated enough.

As it grows, C. botulinum produces a potent toxin that affects the nerves of it’s host. The first symptoms can appear within 12 hours. As well as fatigue, muscle pain, or difficulty swallowing, botulism can cause severe vomiting, double vision and patients being unable to keep their eyelids open.

All of the victims in the 1922 case died within of three days of consuming the contaminated duck paste. It was ruled that the case was a tragedy and staff were not held accountable for any intended wrongdoing. But Alexander Robertson struggled to come to terms with the food poisoning deaths in his hotel — by January 1925 he could no longer live with the guilt. He was laid to rest in the ancient burial ground on Isle Maree.

Read another story from us: 2000-year-old preserved loaf of bread found in the ruins of Pompeii

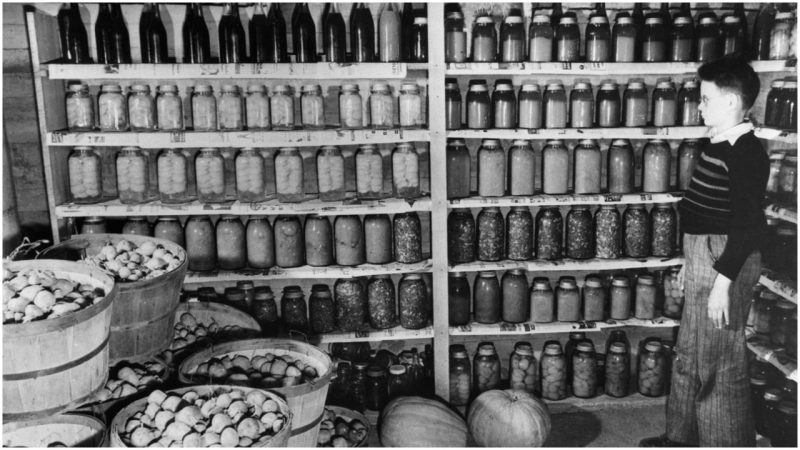

The case prompted more serious research on the deadly illness and how it can be properly treated. It also led to the introduction of legal regulations which concerned producing home-canned foods.