Flying broomstick? A pointy hat? Damp and dark hideout, full of bizarre ingredients, with fumes coming out of several pots and pans at once? A black cat?

These are all traits traditionally related to the depiction of witches in literature and popular culture in general.

However, according to a study conducted by Stacy McLennan, Collections Curator and Registrar of the Waterloo Region Museum in Canada, the origin of these stereotypes dates back to medieval times and a potion-making profession of a different kind.

McLennan draws a striking parallel between the way that we imagine witches today with the appearance of women involved in the beer-making industry of the Dark Ages.

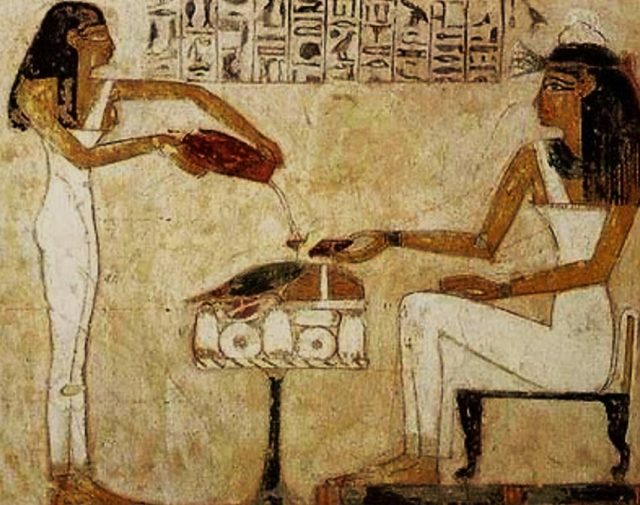

Even though beer was a known beverage in Egypt and Mesopotamia thousands of years before, it wasn’t until the 1300s that it became associated with witchcraft. According to McLennan, the answer lies in a successful attempt to suppress women from this line of business, and turn medieval craft beer into a “manly man’s profession.”

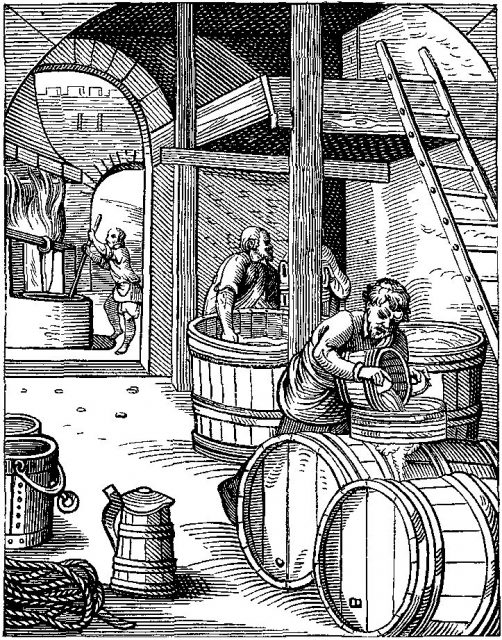

During the 14th century, ale-making was a trade mostly reserved for women who competed to produce the best flavors and blends, while developing the science of beer-making.

Reports from the period right before the Great Plague hit England mention more than 300 women in Brigstock, Northamptonshire, brewing beer for sale and making a significant profit by doing so.

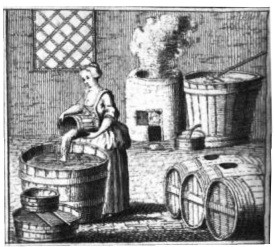

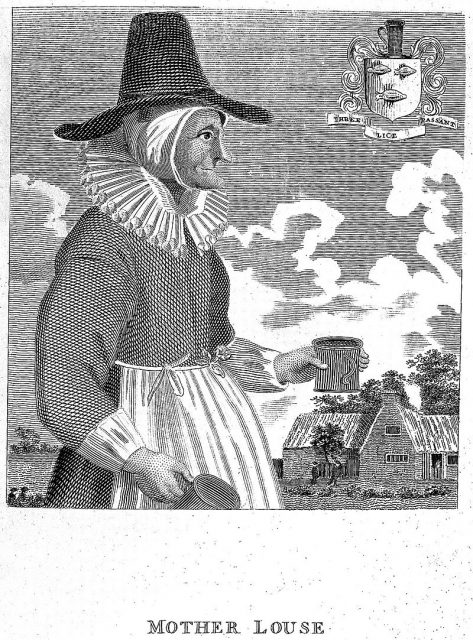

Commonly known as Alewives, these women used a number of tools and equipment like a bubbling cauldron full of hot brown liquid and a broom for tidying up.

In the marketplaces, brewers wore high-pointed hats to stand out from other merchants. Eventually, the hat became a symbol of the trade.

Furthermore, an animal which became the usual side-kick of witches was the alewives’ cat, useful for catching various vermin and rodents that jeopardized production by eating grains and other stored cereals vital for the making of beer.

And last but not least, the inevitable prop present in every witch’s arsenal — the broomstick.

The story behind the broomstick being so commonly related to witches comes from what was once called an ale-stake. To signal potential customers that the ale was ready for distribution, the alewives of old used a tall stake, reminiscent of a broom, which would be exhibited in front of their house.

But what caused the image of these female entrepreneurs to suddenly turn sour?

Well, the answer to that question is unfortunately very simple — profit.

As brewing involved more and more women across England and continental Europe, men wanted a slice of this lucrative enterprise. Better yet, the whole pie.

By the mid-14th century, the Church had begun their campaign of fabricating the narrative that alewives were in fact servants of the devil, and that beer is the Unholy’s favorite alcoholic beverage.

Soon various depiction of women as Satan’s loyal servants arose as decorations in Christian churches. Stacy McLennan explained for the CBC News in 2015:

“There are more depictions of alewives in hell during this time period than any other profession. Most medieval churches in England have some sort of painting or carving or some sort of depiction of an alewife in hell in the Last Judgment scene.”

Tools such as the hat and the broom were decried as symbols related to witchcraft. It quickly caught on, as alewives began losing their customers, who simply switched to buying from their male counterparts for fear of being possessed by the alchemy of a woman’s brew.

But for the women who were known to be involved in beer-making, this sudden shift didn’t only cost them their business. In a time when life was cheap and accusations of heresy ran rampant, to be called a witch was an immediate death sentence.

Apart from the fact that in following centuries beer production became an exclusively male profession, no reliable records exist of how many of the ale-wives lost their lives during witch hunts, so common in the Middle Ages.

In 15th and 16th century Spain, a similar scenario caught up with a large number of female tavern-owners and brewsters, as the infamous Inquisition scoured the land in search of heretics, and often produced fictional proof of witchcraft.

Nikola Budanovic is a freelance journalist who has worked for various media outlets such as Vice, War History Online, The Vintage News, and Taste of Cinema. His main areas of interest are history, particularly military history, literature and film.