The SS was the most German of Nazi organizations, but that there were non-German SS members is not far-fetched at all. For those people just learning about some of the finer details of the war, it can at first seem unbelievable that the SS, the most racial of all Nazi organizations, might include non-Germans, but it did. Hundreds of thousands of them.

Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS and its armed branch, the Waffen-SS, was determined to make the Waffen-SS into an organization which included men of “Germanic stock” from all over Western Europe. That was the initial idea. By the summer of 1940, Hitler’s Third Reich had expanded to include most of Western Europe and part of Scandinavia. In some countries, there had been a sizable fascist presence before the war which looked to Berlin for leadership.

Volunteers from Holland and Belgium began to join the Waffen-SS almost immediately after the fall of their nations to Hitler. This also occurred in both Denmark and Norway and even included Swedes who in large part were motivated by an intense anti-communism. These two groups formed the core of two regiments which in turn grew and became the 5th SS Panzer Division “Wiking.”

Other units followed: French, Spanish, Italians, Slovenes and ethnic Germans from the Baltic States volunteered for the Waffen-SS, as did some Finns. At one point during the war, the ranks of the Waffen-SS reached nearly one million men.

However, this was not enough — the attrition rate was greater than the number of men coming in, especially for the Waffen-SS, whose fighting style was offensive to the point of recklessness. Additionally, though in 1940-41 the units of the Waffen-SS were relatively green and exposed themselves to enemy fire needlessly, by 1942 they had become the “fire brigade” of the Third Reich, especially on the Eastern Front. Where the fighting was thickest or the direst, there you would likely find units of the Waffen-SS.

Himmler was also secretly enthralled by the idea of the ideological SS replacing the Wehrmacht as Germany’s armed force. To do this, and to refill his ranks, he expanded his search. Soon there were Croatian, Montenegrin, and even a small Hungarian contingent. Bosnian Muslims formed a unit.

There were even small units which included British and even Indian POW. A very large contingent of Ukrainians were in the SS, both manning the concentration/extermination camps and in the Waffen-SS fighting Soviet partisans.

Initially, the requirements for SS membership were applied to volunteers from other European nations. Frenchmen, Dutch, Norwegians and the others from Western Europe were considered “Germanic” by Himmler and simply had to show their lack of Jewish ancestry to join (as well as meet physical requirements).

Later, as the war expanded, volunteers from other nations had to swear they were not Jewish, but a sort of blanket “Germanism” was thrown over them. One of the requirements was being anti-communist.

In 1942, the Germans had driven to the Volga River at Stalingrad and southwards into the Caucasus. There they were greeted as liberators by some. Among these were large numbers of Georgians, who were inspired by a hatred of not only the Soviet system, but of Stalin himself.

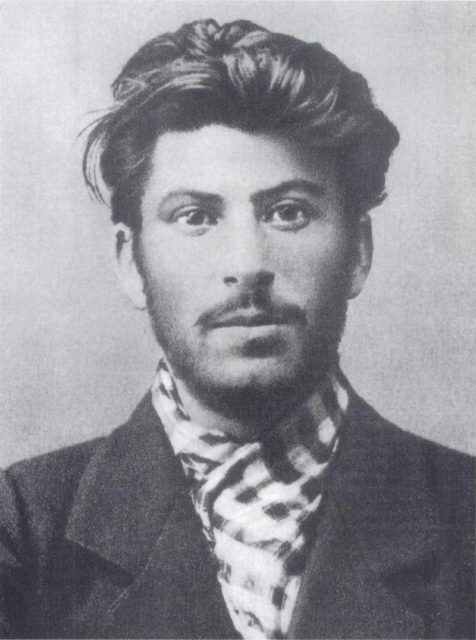

Stalin was born Iosef Dzugashvili — a Georgian — and to many, it seemed like he had spent most of his career trying to put his Georgian roots behind him. Much of Georgian culture was suppressed: language, alphabet, history, etc.

The logic used by Himmler in allowing Georgians into the SS was this: they were from the Caucasus, considered to be part of the original “homeland” of the Aryan people, they were anti-communist, not Jewish and not Slavic. Hitler himself was cool on the idea, having mixed notions about their “race,” but influenced by a number of defections of Georgians back to the Soviets.

Some thirteen battalion-sized units of Georgian SS volunteers were formed from 1942-43, approximately 30,000 men. Though some of these volunteers had been living in Germany as refugees from the time when the Soviets took over Georgia (1921) and were rabidly anti-communist, many other volunteers came to quickly regret their choices, as Axis troops were soon pushed out of the Caucasus, never to return. Together, these units were called “The Georgian Legion.”

By the end of the war, many of the Georgian units were not even on the Eastern Front. A large number were doing garrison duty in the West, allowing German troops to be transferred to the front lines. One of these units was the 822nd Infantry Battalion “Queen Tamar,” stationed on the Dutch island of Texel.

The September 1944 attempt of the Allies to liberate all of Holland and sweep into Germany (Operation “Market Garden”) had failed, and at wars’ end, much of Holland was still under German control, especially the numerous islands on the coast, which had been fortified early in the conflict.

Unlike some of the other Georgian units, the 822nd was made up of former Red Army POW’s, who had been given a choice: remain in German POW camps, or fight for the Third Reich. Being that over 50% of all Soviet prisoners died in German hands, the choice was relatively easy.

The unit had seen anti-partisan fighting in summer 1943, but was transferred to Holland in the fall, where they remained. In spring 1945, the unit consisted of 800 Georgians and 400 Germans.

By the spring of 1945, the war was nearing its end. The men of the 822nd, not knowing their fate, were not going to throw their lives away on some last ditch effort by the Germans to delay the inevitable, so when the Germans ordered the unit to attack advancing Allied columns, they revolted. In the days previous to their revolt, contact had been made with the Dutch underground for support.

On April 6, 1945 the Georgians of the 822nd snuck into the Germans’ barracks and killed a great many of them while they slept. Others on guard duty were also killed. Some members of the Dutch Resistance joined them in their attacks.

Most of the island fell under Georgian control in a short time, but unfortunately not the artillery positions on the north and south ends of the island, which radioed for help and began to shell suspected rebel positions. Reinforcements from German naval infantry nearby soon joined the battle, which went on for an amazing five weeks, which was past the official end of the war. Fighting went on until May 20th, when a unit of Canadians marched in and disarmed the Germans.

565 Georgians, over 800 Germans and a number of Dutch civilians died during the battle, which has been called “The Last Battle of WWII in Europe.” The 228 Georgians that survived were turned over to the Soviets, most perished in the Gulag. A very few who survived were allowed home in the 1950s. Today, a memorial to the dead on Texel marks the site of the rebellion.

Matthew Gaskill holds an MA in European History and writes on a variety of topics from the Medieval World to WWII to genealogy and more. A former educator, he values curiosity and diligent research. He is the author of many best-selling Kindle works on Amazon.