In the years leading up to World War 2, and throughout, many of the major world powers were working on advancements within the nuclear field. The Americans, the British, the Germans and the Soviets had a keen awareness of the potential for nuclear weapons during the 1930s, when testing had revealed the potential for explosions.

With all sides secretly working to find the key to nuclear weaponry, security was of the utmost importance. No side would be willing to share what they learned with those who could potentially use these secrets against them.

Espionage would be the key to gaining secrets about the nuclear programs of other nations. Any country worth their salt would employ dozens of spies in the hopes of gaining glimpses of knowledge of scientific advancements from their enemies, or even their own allies.

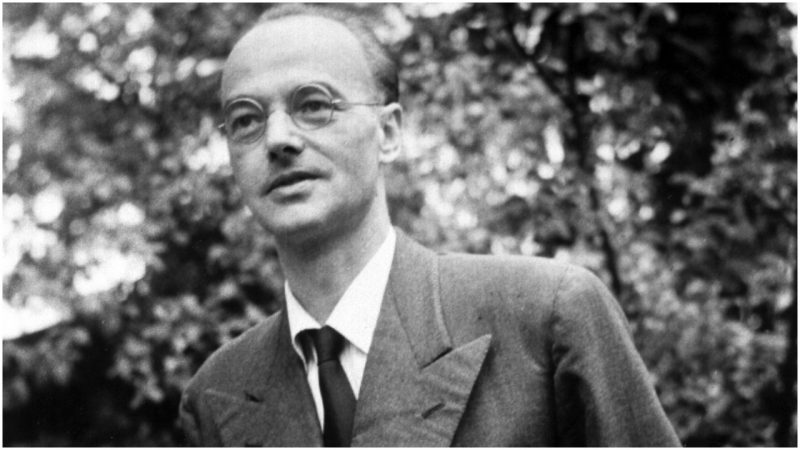

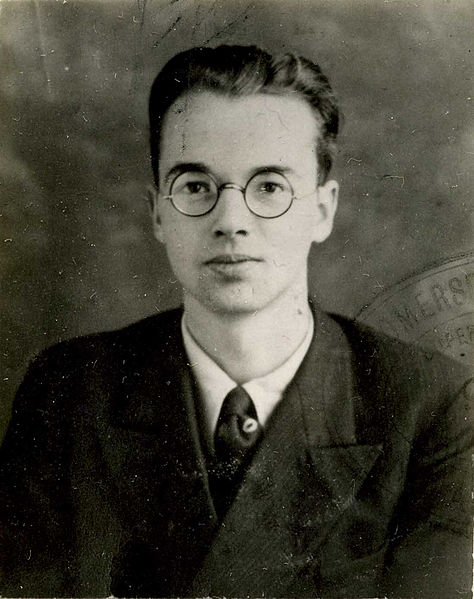

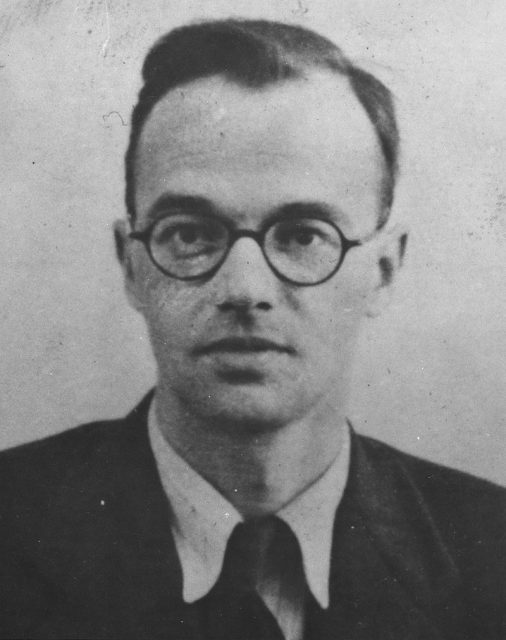

One man, Klaus Fuchs, a theoretical physicist, would prove to be an exceptionally capable spy and would provide secrets to several states, all the while working under British supervision.

Klaus, though born a German in 1911, was not sympathetic to the growing Nazi cause that surrounded him in his youth and early adulthood. His political alliances belonged at first to the Socialist party of Germany and then later the Communist party, where he ardently opposed the rise of the National Socialist Party, also known as the Nazi party.

Klaus’ communist leanings were what convinced him that he would no longer be safe within Germany once Hitler became the Chancellor. Knowing that the fascist Nazis would seek to eliminate all political opposition, he fled to England in 1933. A student of science, Klaus Fuchs continued his education unhindered from the oppressive rule of the Nazis.

As he worked in England, it became clear that there would be no return to Germany and so Klaus Fuchs applied for British citizenship. This became a tangled web of problems, however, as war had broken out between Germany and England. Since Klaus was a German, he was sent to an internment camp in Quebec, Canada. This was done as a measure to prevent any enemy German operators from acting within the British borders.

Things You May Not Know About James Bond

Undeterred by such measures, Klaus continued his work as a physicist, publishing several papers and eventually making contact with members of the communist party. These members had been involved with assisting Jurgen Kuczynski to organize a communist movement within Britain itself. These contacts would prove extremely valuable to Klaus once he was released from the camp in 1940. After his release, he was able to secure for himself British citizenship and would soon find himself working on the British atomic bomb project.

Yet, despite the British trust for Klaus, who had sworn to secrecy about the projects he had been working, he had other plans for the information he was learning. Making contact with the communist party member, Jurgen Kuczynski, Klaus was referred to a member of the Soviet GRU, the intelligence branch of the Soviet Union. Expressing interests in serving the Soviet Union and the communist cause, Klaus began to share British research secrets to the U.S.S.R.

By 1944, Klaus Fuchs was assigned to Los Alamos, New Mexico, to work with the American nuclear program on behalf of the British. Since the United States and Britain were closely allied during the wartime, their nuclear programs often cooperated with one another. This would give Fuchs even more access to research secrets and he had no trouble at all with relaying what he was learning back to the Soviet Union. Throughout World War 2, he was never suspected nor caught for his spying. Rather, thanks to the research that he was doing, Klaus was held in high regard by the British as a top scientist.

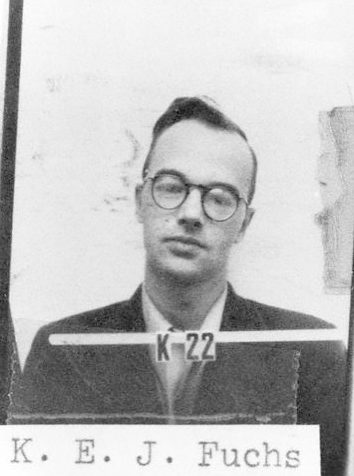

Once the war was over, Fuchs returned to Britain and continued his work in the British atomic research program, still sending valuable data to the Soviets. However, his luck would run out in 1949, when the American Intelligence’s Venona Project revealed that he had been in communication with Soviet cables.

The British, skeptical of this information due to how much use Fuchs had been to them, investigated the situation. At first, Klaus Fuchs denied that he was a spy, but in 1950, he would ultimately end up confessing his crimes in totality.

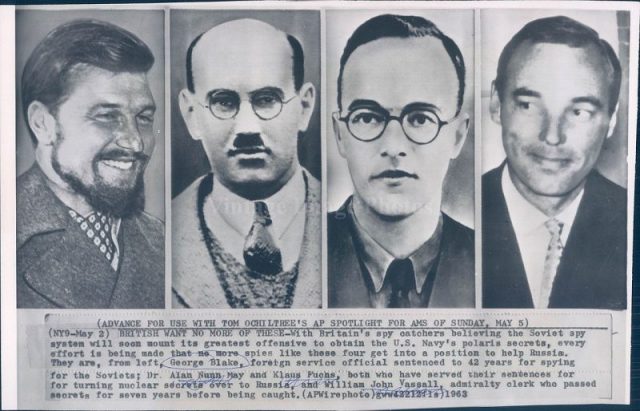

Undoubtedly the British were shocked at such a confession, but Fuchs’ testimony did lead to the arrest and imprisonment of other spies that were operating in the region. Fuchs was arrested and sentenced to 14 years for his acts of espionage.

Since the Soviet Union were technically allies at the time, in spite of the growing tensions, Fuchs sentence wasn’t as severe as it could have been. His citizenship stripped, he spent nine years in prison before being released for good behavior.

There is a question about the effectiveness of Fuchs’ espionage. While it is undeniable that he was able to steal plenty of secrets and relay them to the Soviet Union, the Soviet policy at the time was only to use stolen research as a means of checking against their own research.

The dangers of counter-espionage were too great, false data leaked to the nuclear program could lead to serious disaster and loss of valuable time. Still, there are those who argue that thanks to Fuchs, the Soviet timetable to gaining access to nuclear weaponry was bumped up by one to two years. Regardless of the effectiveness of the information provided, Fuchs was certainly one of the best spies to have worked in the British nuclear program.

Andrew Pourciaux is a novelist hailing from sunny Sarasota, Florida, where he spends the majority of his time writing and podcasting.