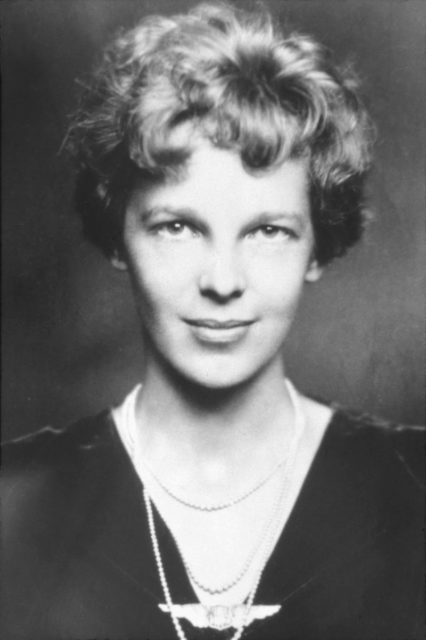

It was such a shock to the world in 1937 when celebrated aviator Amelia Earhart disappeared during a flight over the Pacific that some people just couldn’t believe it.

At least that is what the military said was the cause of dozens of reports of distress calls from Earhart. People said they were picking up fragments of messages from her on shortwave radio in the days immediately after her disappearance. But the officials insisted that the calls were not from her. People must be upset and confused or trying to get attention.

Now there’s a new report out making the case that most of these transmissions were genuine. The report was delivered at a conference by the International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR). The group’s leading theory is that Earhart and her navigator lived for a short time on the deserted Gardner Island, later called Nikumaroro.

Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, may have been able to send out messages on a two-wave radio for a short time, they say. “Will have to get out of here,” a woman could be heard saying at one point, according to the paper containing TIGHAR’s research. “We can’t stay here long.”

“Amelia Earhart did not simply vanish on July 2, 1937. Radio distress calls believed to have been sent from the missing plane dominated the headlines and drove much of the U.S. Coast Guard and Navy search,” Ric Gillespie, executive director of TIGHAR, told Discovery News.

“When the search failed, all of the reported post-loss radio signals were categorically dismissed as bogus and have been largely ignored ever since,” he added.

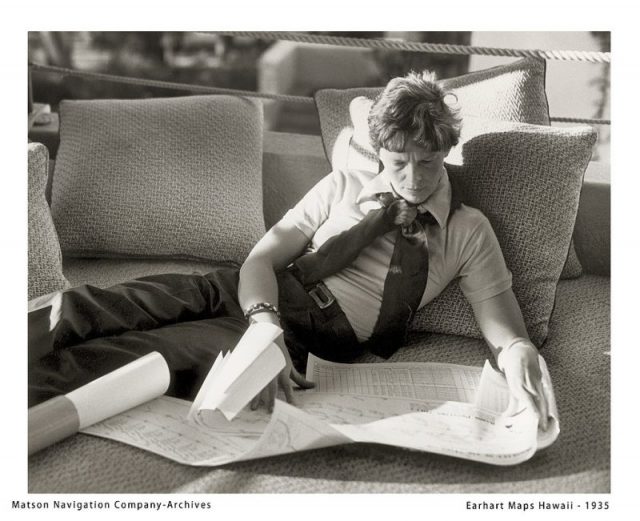

Using digitized information management systems, antenna modeling software, and radio wave propagation analysis programs, TIGHAR re-examined all the 120 known reports of radio signals suspected or alleged to have been sent from the Earhart aircraft after local noon on July 2, 1937 through July 18, 1937, when the official search ended, according to NBC.

The conclusion is that 57 out of the 120 reported signals are credible.

A woman in Toronto heard the voice say, “We have taken in water . . . we can’t hold on much longer.”

Earhart and Noonan could only use the radio for a few hours each night when the tide was low in order to not flood the engine as the plane rested out on the island’s reef, the Washington Post reported.

The day after the crash, a Kentucky woman claimed she heard someone say “KHAQQ calling,” before saying “on or near little island at a point near…” and “something about a storm and that the wind was blowing,” according to the Post.

With Noonan as her navigator and only crew member, Earhart left Oakland, California, on May 20, 1937, for Miami (with stops along the way), where she announced her intent to circumnavigate the globe. From there, they flew across South America, Africa, India, Southeast Asia, arriving at Lae in New Guinea on June 29, 1937. With 20,000 miles behind them, they had only 7,000 left over the Pacific Ocean.

On July 2, 1937, Earhart and Noonan took off from Lae with the intention of landing on Howland Island. They never made it.

A ship, the USCGC Itasca, was stationed at Howland Island to help Earhart navigate landing her plane.

At 7:42 a.m., she radioed: “We must be on you, but cannot see you–but gas is running low. Have been unable to reach you by radio. We are flying at 1,000 feet” At 8:43 a.m., Earhart reported, “We are on the line 157 337. We will repeat this message. We will repeat this on 6210 kilocycles. Wait.” And a few moments later: “We are running on line north and south.”

The search for Amelia Earhart was abandoned. The leading theory was that she crashed into the ocean and they sank. But there were always those who doubted the official version, who believed she survived for a short time. and was perhaps even spotted and taken prisoner by the Japanese.

“The results of the study suggest that the aircraft was on land and on its wheels for several days following the disappearance,” Gillespie said.

The research group believes that Gardner Island, an uninhabited atoll in the southwestern Pacific, is where Earhart and Noonan landed safely but ultimately died as castaways.

Nancy Bilyeau, a former staff editor at Entertainment Weekly, Rolling Stone, and InStyle, has written a trilogy of historical thrillers for Touchstone Books. For more information, go to www.nancybilyeau.com.