The woman who discovered proof that thousands of Japanese-Americans who were incarcerated in the United States during World War II were held for reasons of racism, not national security, has died. Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga was 93.

Bruce Embrey, co-chair of the Manzanar Committee, informed the media that Herzig-Yoshinaga died on July 18th at her home in the California city of Torrance.

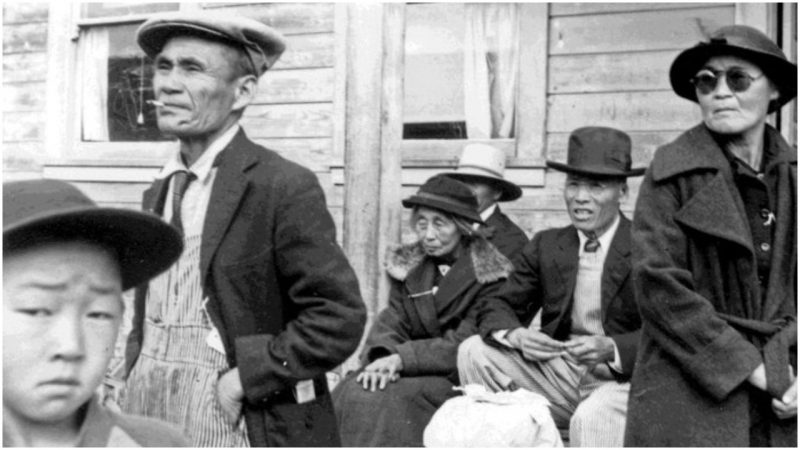

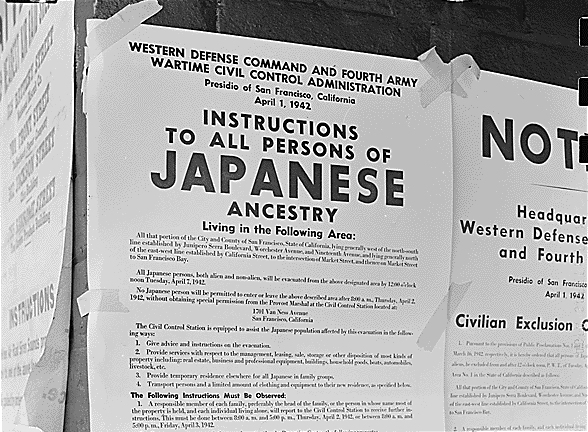

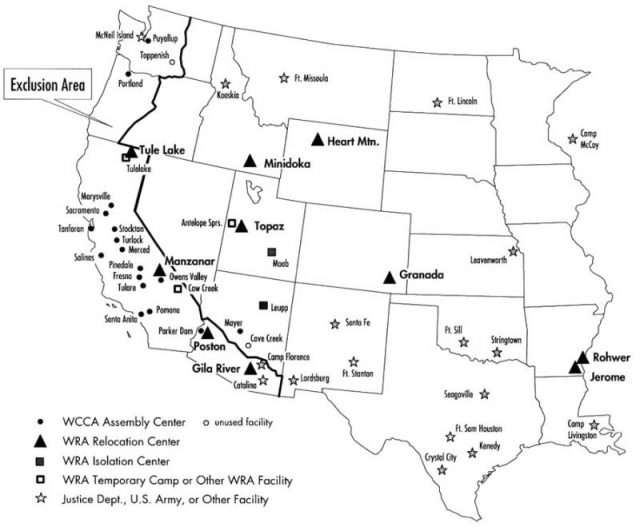

About 120,000 Japanese-Americans were held in camps during World War II. The reason given for their being confined was national security, and there was no time for the lengthy investigations to determine who could be a spy, versus who was loyal to the United States.

It was the largest single forced relocation in American history.

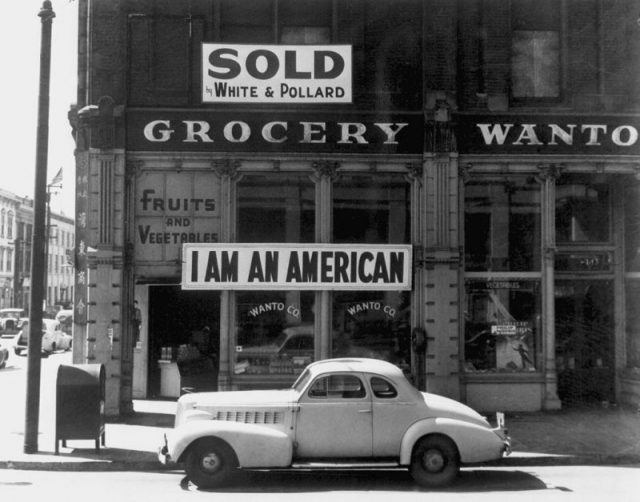

On December 7, 1941, the United States entered World War II as Japan attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor. “At that time, nearly 113,000 people of Japanese ancestry, two-thirds of them American citizens, were living in California, Washington, and Oregon,” according to the National Park Service. “On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order No. 9066 empowering the U.S. Army to designate areas from which ‘any or all persons may be excluded.’ ”

No person of Japanese ancestry living in the United States was ever convicted of any serious act of espionage or sabotage during the war.

Aiko Yoshinaga was born in 1924, in Sacramento, California, to Japanese immigrant parents. They moved to Los Angeles when she was a child.

Yoshinaga was a 17-year-old senior at Los Angeles High School when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Soon after, she learned she and 14 other Japanese-American students at her school would not graduate with their Class of 1942.

“You don’t deserve to get your high school diplomas because your people bombed Pearl Harbor,” she recalled her school’s principal telling them.

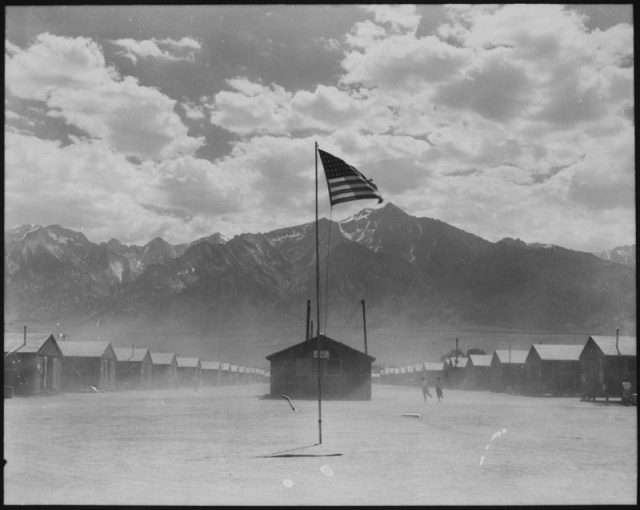

After being denied graduation, she eloped with her fiance. But the couple were forced to report to the Manzanar camp. “Now a historical site, it was then a sprawling, barbed-wire enclosed makeshift prison perched on a dry, dusty, barren region of California’s high desert and surrounded by guards,” said NBC. “It was there, in a tarpaper-covered barracks shared by three families, where she gave birth to her first child.”

The rest of her family had already been sent to the Santa Anita racetrack, and then transferred to a camp in Arkansas. There her father died.

Yoshinaga moved to New York after the war ended and she was released from the camp. She divorced, had two more children, and divorced again. As a single mother in the 1960s, she found herself often wondering about her internment.

“I hooked up with a group called Asian Americans for Action,” she said during a Manzanar Committee event in 2011 honoring her with a legacy award. “They turned my head around. They got me to think, ‘Yeah, I never thought about all the reasons why the government did this to us.’ ”

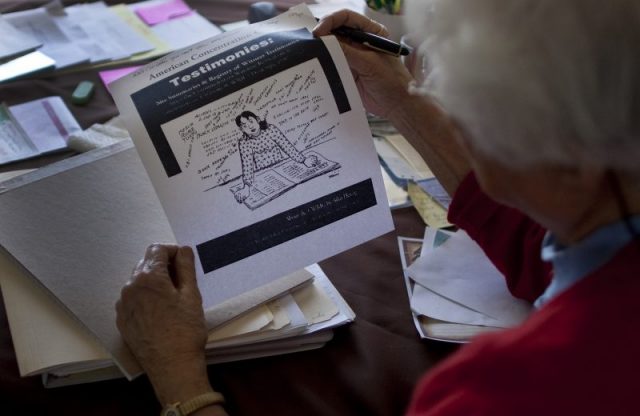

After moving to Washington D.C., she spent time researching the war in the National Archives. Her tireless reading of documents found one that sent shockwaves through the country.

The document she discovered was the original version of a 1943 government report arguing the Pentagon’s claim that the evacuation was a military necessity.

It said that it was “impossible to establish the identity of the loyal and the disloyal with any degree of safety” and added: “It was not that there was insufficient time in which to make such a determination; it was simply a matter of facing the realities that a positive determination could not be made, that an exact separation of the ‘sheep from the goats’ was unfeasible.”

The discovery was part of research that helped lead to a congressional commission’s conclusion in 1983 that the wartime internment was, instead, prompted by “race prejudice, war hysteria and the failure of political leadership.”

“Her discovery of that original published justification, which was then later altered 180 degrees, revealed that the motivation for incarceration was not really a military necessity but outright racism,” said San Francisco attorney Dale Minami to NBC. He had used it as evidence in getting wartime convictions vacated for those who refused to report to relocation camps.

The resulting investigations and committee findings resulted in President Ronald Reagan issuing a formal apology and the awarding of $20,000 each to those who had been interned during World War II.

“She was just a regular person who was wondering, ‘Why was I plucked out of high school before my senior year and not allowed to graduate?’ And that drove her personal crusade,” Minami said to the media.

“She was just a lovely woman, very kind and generous,” he added. “You could even call her sweet and cute. But that belied a real commitment to social justice. Not just for Japanese-Americans but for all marginalized groups.”

Nancy Bilyeau, a former staff editor at Entertainment Weekly, Rolling Stone, and InStyle, has written a trilogy of historical thrillers for Touchstone Books. For more information, go to www.nancybilyeau.com.