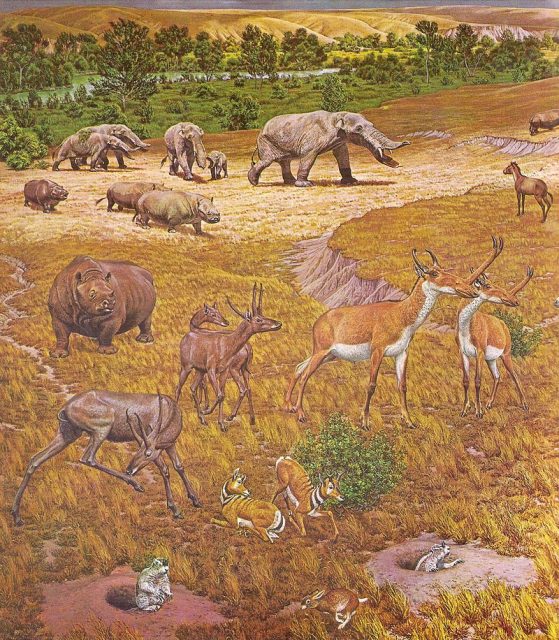

During the Pleistocene epoch, approximately 12,000 to 2.5 million years ago, and well before the Conquistadors ever set foot on North American soil, bringing their Spanish horses with them, indigenous horses once roamed the continent. And alongside them were some seemingly unlikely mammalian companions: camels.

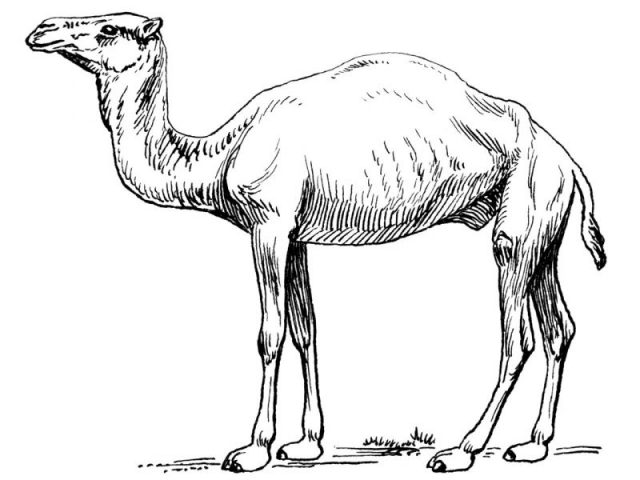

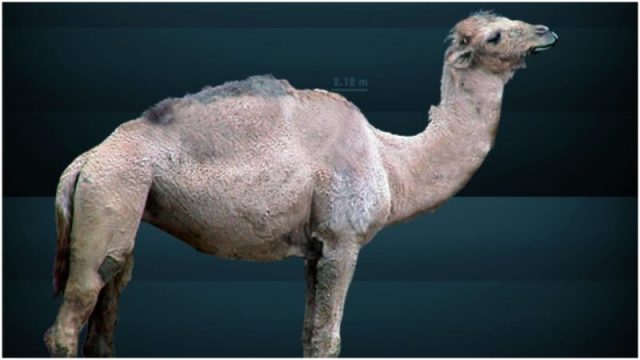

Many are familiar with the “stars” of the Ice Age – woolly mammoths, sabre-tooth cats, enormous bison – but it is less known that a type of camel, known as Camelops, once roamed the western part of North America. This animal was a common ancestor of both the Old World Dromedary and Bactrian camel, so is considered a “true” camel.

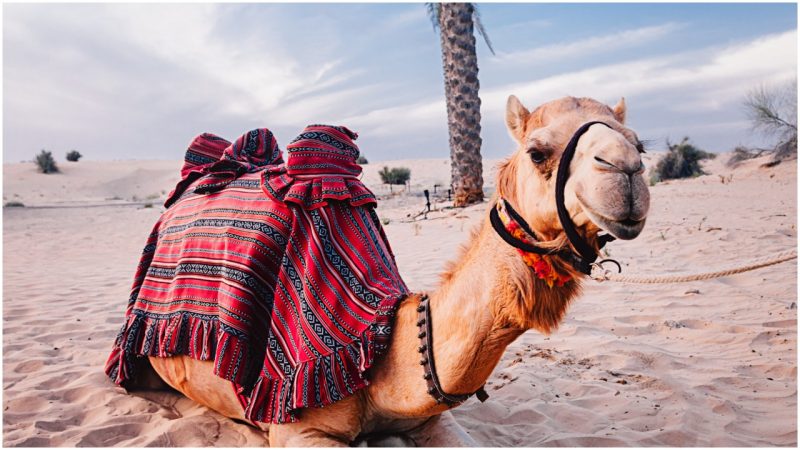

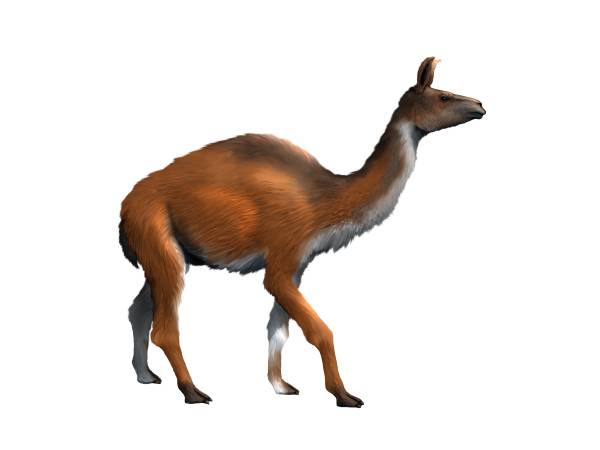

One might be surprised to think of camels – typically associated with hot, dry deserts – wandering across the chilly plains of Western North America. However, the family Camelidae, which includes both camels and llamas, actually originated in North America during the middle of the Eocene epoch, roughly 44 million years ago.

They later, along with early horses, migrated to Asia across the Bearing land bridge, whereas humans came in the opposite direction. Modern camels are also descended from the Paracamelus, which continued to live in North America until the middle Pleistocene and became known as the High Arctic Camel.

With the extinction of Paracamelus by the end of the Pleistocene, Camelops was the only remaining camel in North America. Its subsequent extinction was likely caused by the larger North American disappearance of mastodons, horses and other animals, known as the Blitzkrieg model, and was chiefly due to prolific hunting as humans moved across the continent from the north-west to the south-east, as well as rapid climate change.

It is uncertain whether Camelops had a hump – soft tissues are rarely preserved as fossils – however, as one-humped camels are known to be descended from two-humped versions, it can be surmised that Camelops likely also had two humps.

Humorously, there was one fossilized mammal that is now known as the “Walmart camel,” having been discovered at the site of an Arizona Walmart store. While originally believed to be a camel, studies of the remains have proved to be inconclusive as to their precise identity.

Together with native camels, North America also hosted its own horses, many fossils of which have been discovered at the Hagerman Fossil Beds near Hagerman, Idaho. This site is home not only to Camelops fossils but also to the largest concentration of Hagerman Horse fossils in North America.

The Hagerman Horse, formerly known as Plesippus shoshonensis, is one of the oldest horses of the Equus species and was discovered on this site in 1928, hence its name. At one time, there were many horse-like mammals on Earth, all belonging to the family Equidae. However, the genus Equus is the only surviving genus of this group.

Mounted skeleton of a Hagerman horse.

Also known as the Hagerman zebra or American zebra, the Hagerman Horse was about 43-57 inches tall at the withers, or 11.3 to 14.1 hands high, for those who “speak horse.” In other words, it was about the size of a pony, although it has also been compared in size to an Arabian horse. They were quite stocky, much like highland ponies of today, with thick necks and straight shoulders, and narrow skulls like donkeys.

Read another story from us: Possibly the World’s Oldest “Yo Mama” Joke Found on a Tablet in Iraq

The site in Idaho is particularly rich, and hundreds of fossils were uncovered at the Hagerman Horse Quarry in the 1920s and 30s. This location may have once been a watering hole, or perhaps an entire herd was caught in a flood and ended up at this point once they were drowned.

Hagerman Horses did not remain in North America but are believed to also be have lived in some parts of Europe, including France, Germany, Italy, and Greece.

Patricia Grimshaw is a self-professed museum nerd, with an equal interest in both medieval and military history. She received a BA (Hons) from Queen’s University in Medieval History, and an MA in War Studies from the Royal Military College of Canada, and completed a Master of Museum Studies at the University of Toronto before beginning her museum career.