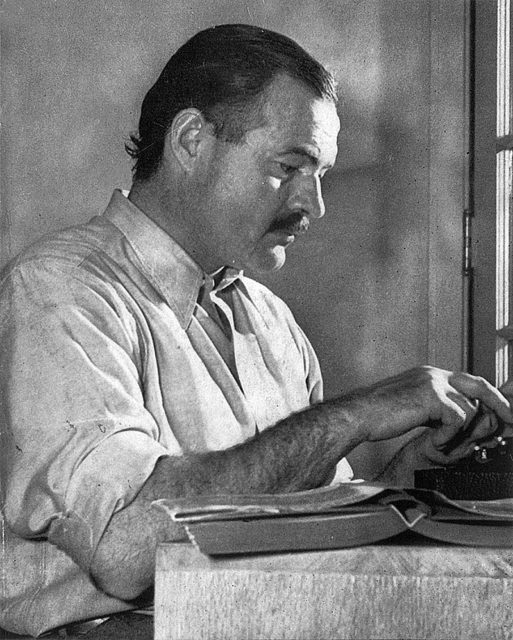

When Ernest Hemingway committed suicide in 1961, the world stood in awe. His talent and his adventurous spirit were admired by many, as he was seen as an unbreakable man who enjoyed life to the fullest.

Numerous theories were spawned over the course of decades regarding the true reasons behind the famous author taking his own life.

Some claimed it was due to money issues, others blamed his troubled marriage. There were also theories that Hemingway might have contracted terminal cancer.

However, in 2011, Aaron Edward Hotchner, the writer’s biographer and long-time friend came out with the most viable explanation to date. Hotchner was Hemingway’s trusty companion during the last 13 years of his life, joining him on various escapades in Cuba and Europe.

A writer, journalist, and editor himself, Hotchner adapted several of Hemingway’s novels and short stories for film and television.

According to him, the writer was faced with two major ordeals in his later life.

First was a conviction that his most lucrative years as an author were long gone and that he would never be able to produce literary work of the likes of For Whom The Bell Tolls or The Sun Also Rises. Hemingway had confessed to Hotchner that he felt unable to finish his mission as a writer on the one hand, while also ruling out the notion of retiring as he considered retirement to be impossible for a writer.

Hotchner recalled his conversation with the Nobel-winning writer in an interview for the New York Times in 2011:

“Unlike your baseball player and your prizefighter and your matador, how does a writer retire? No one accepts that his legs are shot or the whiplash gone from his reflexes. Everywhere he goes, he hears the same damn question: what are you working on?”

The second idea that plagued Hemingway, and ultimately led him to suicide, was a fear of being followed by the FBI. Hotchner recalls in detail bursts of paranoia during the last years of his life, spent in his reclusive resort in Ketchum, Idaho.

As early as 1959, Hemingway seems to have been seriously distraught by the notion that he was being constantly followed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, which he claimed bugged his home and even his automobile.

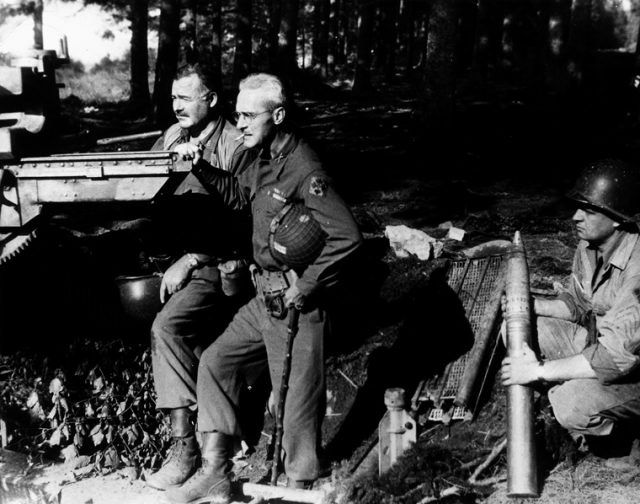

In the NY Times interview, Hotchner painfully recalled a situation when he arrived to visit Hemingway in Idaho, together with Forrest “Duke” MacMullen, the writer’s old hunting pal. It was November 1959, and the three friends had arranged a pheasant shooting trip.

Instead, Hutchings and MacMullen were met with a mad old man who appeared to be haunted by various demons, whom he called “the feds“:

“It’s the worst hell. The most goddamned hell. They’ve bugged everything. That’s why we’re using Duke’s car. Mine’s bugged. Everything’s bugged. Can’t use the phone. Mail intercepted.”

The very last romantic words spoken.

His ramblings continued until he went silent, only to burst into another rant about the federal agents going through his financial accounts. During dinner in a local bar with the writer and his wife, Mary, Hemingway asked them to leave early as he was convinced that the two men sitting close to their table were also federal agents.

The situation looked grim. Mary expressed her worries to Hotchner, for she was strugging to cope with her husband’s crippling paranoia.

By the end of the month, the author was admitted to the psychiatric section of St. Mary’s Hospital in Rochester, Minnesota, using a fake name to avoid publicity. There he was subjected to 11 electric shock treatments, believed back then to be helpful with mental illness.

Of course, such torture only worsened his state.

Less than two years after, the writer put a shotgun to his head, ending a complex and beautiful life filled with inner turmoil.

But was it all a conspiracy theory devised by an elderly writer’s imagination? Or was Hemingway indeed followed by the FBI, who documented his whereabouts, read his mail and listened to his daily conversations?

In January 1983, a professor of English at the University of Colorado, Jeffrey Meyers, used of the Freedom of Information Act to obtain a 124-page file kept by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Meyers discovered something about the writer’s past which he had kept secret even from his closest friends. It was this past that came to haunt him so many years later.

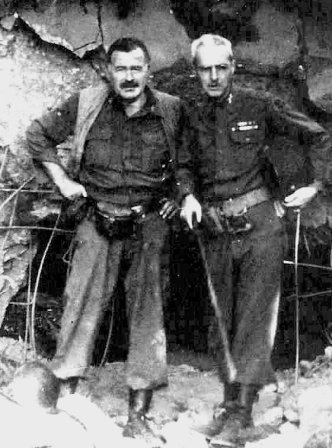

During WWII, while Hemingway was in Cuba, he devised a plan together with the then-U.S. ambassador in Havana, Spruille Braden, to keep an eye on Spanish citizens residing in Cuba who had connections with the fascist Franco government in Spain.

Hemingway had reasons to suspect that they were somehow trying to lobby Cuba into joining the Axis cause.

For the purpose of thwarting their plans Hemingway, who was a sworn anti-fascist, set up an amateurish intelligence unit which he called “The Crook Factory,” in which a network of spies loyal only to him worked around the clock, shadowing their targets and thus preventing them of taking further action.

For his service, the writer received a monthly salary of $1,000 and a large amount of gasoline, which was scarce at the time due to the war effort.

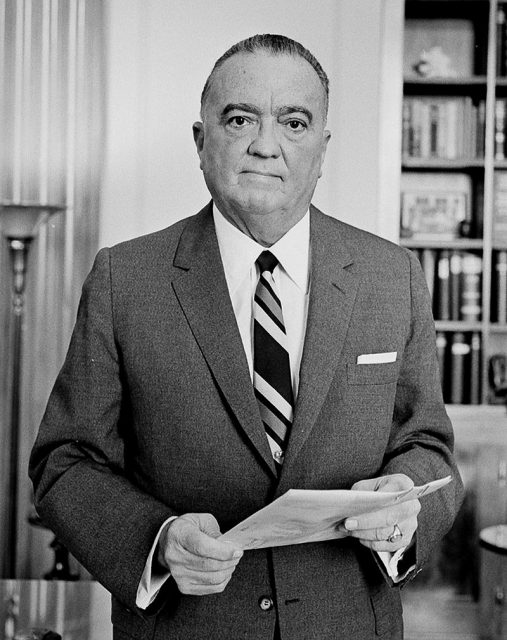

However, while the U.S. ambassador strongly supported Hemingway in his contribution to the struggle, some elements in the FBI considered him a communist sympathizer and were thus hesitant in taking his reports seriously.

During this time, the writer developed a resentment towards the FBI officials who were assigned to monitor his activities — ironically calling them “Franco’s Iron Cavalry” and a bunch of “Nazi mediocrity.”

After he reported a sighting of an enemy submarine in Cuban waters, which couldn’t be confirmed by official channels, his intelligence operation was shut down and the FBI focused more on him and his contacts with the former Spanish Republicans.

Even J. Edgar Hoover took an interest in writer’s whereabouts and the question of where exactly he stood during WWII politically. Thus, the file which is today open to the public was kept on him for the most of his life.

It was proven that his phones were tapped and that his correspondence was monitored. Evidence implies that even the telephone at St. Mary’s Hospital was under surveillance as well.

After learning of this, Hotchner summarized his feelings towards Hemingway and the fact that he, like everyone else, was convinced that what the writer was experiencing was just a product of mental illness:

“In the years since, I have tried to reconcile Ernest’s fear of the F.B.I., which I regretfully misjudged, with the reality of the F.B.I. file. I now believe he truly sensed the surveillance, and that it substantially contributed to his anguish and his suicide.”

Nikola Budanovic is a freelance journalist who has worked for various media outlets such as Vice, War History Online, The Vintage News, and Taste of Cinema. His main areas of interest are history, particularly military history, literature and film.