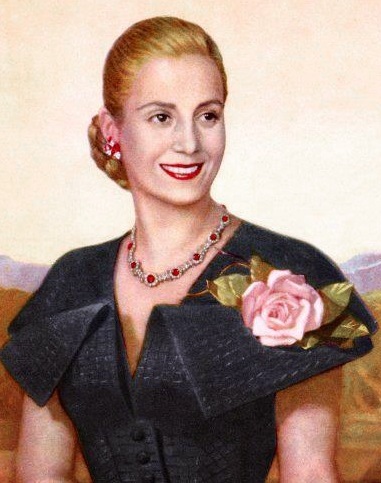

The life of Eva Peron (affectionately known as “Evita”), the glamorous and controversial former First Lady of Argentina, has been well-documented over the years — in articles, documentaries, a 1979 Tony Award-winning Broadway play, and a 1996 big-screen musical, starring another diva, Madonna.

But the details of her demise — an early and tragic one, at age 33 — may be the most fascinating part of her story. It includes a top-secret lobotomy, which took place without her knowledge, as well as the disappearance of her corpse for 16 years.

In 1950, at the height of her popularity and power, Eva was diagnosed with cervical cancer. (Perón’s first wife, Aurelia, also died of the disease, leading some to believe that Perón killed both wives, unknowingly, by passing on the human papillomavirus that led to their death.)

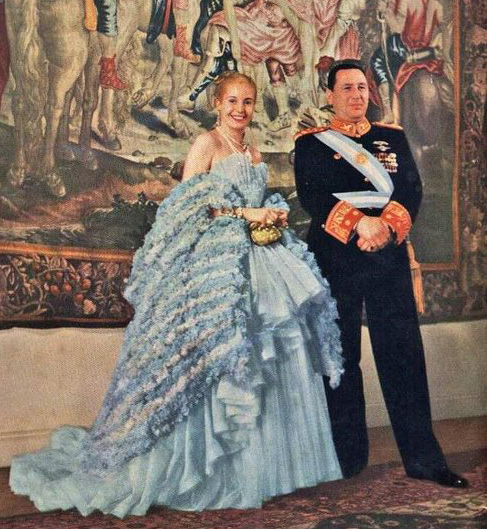

The cancer spread quickly. In June of 1952, Eva accompanied her husband to his second inauguration as President of Argentina. Too weak to stand, and weighing a mere 78 pounds, the frail woman had to be propped up in a cage-like contraption.

Just a few weeks later, Eva would be dead, but her demise may have been brought about not only by her battle with cancer, but by a secret lobotomy, ordered by her husband and carried out shortly before her death.

A half-century later, Daniel Nijensohn, a neurosurgeon at Yale University Medical School, uncovered the truth after examining x-rays of Eva’s skull and talking to acquaintances of the surgeon who reportedly performed the operation, Dr. James L. Poppen, of the Lahey Clinic in Boston.

The controversial procedure, which involves drilling through the skull and severing the connection between the prefrontal lobes and the rest of the brain to numb emotional responses and “stabilize” the personality, was conducted out of concern and fear.

On the one hand, the lobotomy may have been an extreme attempt by Perón to ease the pain his wife was suffering from metastatic cancer. (Though a lobotomy wouldn’t be able to wipe out the excruciating pain, it may have helped her endure it.)

But the mind-altering operation may have also been used to alter Eva’s behavior — in short, to shut her up. In the year before her death, Eva was becoming increasingly unhinged, perhaps due to anxiety resulting from her cancer diagnosis.

Those who didn’t agree with her were deemed “insensitive and repugnant.” She urged her followers to ‘fight the oligarchy’. Even more troubling: Eva, without her husband’s knowledge, ordered thousands of pistols and machine guns, planning to arm workers of the trade unions to form a militia.

Top 5 Female Spies of WW2

Could Eva’s inflammatory statements have led to civil war? Juan Perón may have thought so, and with good reason. As First Lady of Argentina, Eva was more than fashionable arm candy. Perón may have been president and leader of the Peronist party, but his wife also possessed a great deal of power.

She ran the left wing of the party and her every word was followed by a large and passionate group of loyalists. With fractures appearing in the government during Perón’s second term, it’s not far-fetched to think that the political unrest could lead to a full-out revolution.

For Perón, a lobotomy, first introduced in the late 1940s, may have been an answer. The operation was done a few weeks before Eva’s death — in secrecy and without Eva’s consent — in a make-shift operating room set up in the palace. Indeed, the lobotomy would silence Eva, though perhaps not in the way her husband intended. After the procedure she simply stopped eating and eventually died.

Pedro Ara, embalmer extraordinaire, was brought in to preserve Eva’s body for public viewing. He did that — and more. The embalming process, which involved replacing her blood with glycerin, left Eva’s corpse, in Ara’s own words “completely and indefinitely incorruptible.”

Eventually her body was to be placed at the base of an enormous monument. But before the tomb could be completed, Juan Perón was overthrown by a military coup in 1955, and he fled the country before he could secure Eva’s body.

What happened to her remains for the next 15 years would become something of a mystery. Finally, in 1971, military informants revealed it was in a crypt in Milan, Italy, under the fake name Maria Maggi.

Perón had her body — none the worse for wear, save for a missing finger — removed and flown to his home in Spain. He and his third wife, Isabel, would keep her corpse in their dining room, on a platform near the table.

In 1973, Perón came out of exile and returned to Argentina to serve as president once again. He died in 1974 and was succeeded by his wife Isabel, who had Eva’s body returned to her beloved homeland and placed in the La Recoleta Cemetery, burial place of many (formerly) rich and powerful Argentines. Etched in Latin, above marble columns gracing the entrance: the words “Rest in peace.” This time, for good. Eva’s tomb, it is said, is so secure that it could survive a nuclear attack.

Barbara Stepko is a New Jersey-based freelance editor and writer who has contributed to AARP magazine and the Wall Street Journal.