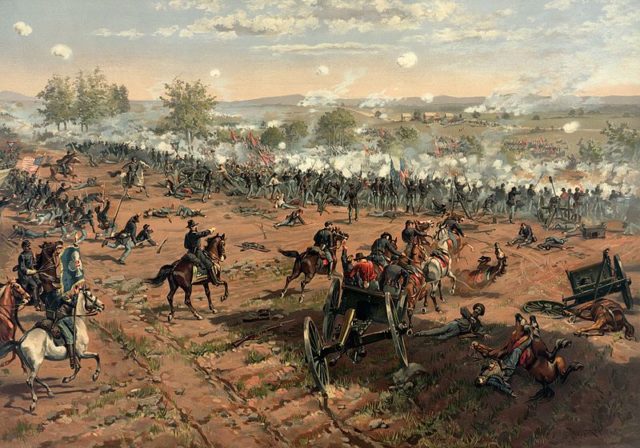

For three days in July 1863, Union and Confederate forces clashed in the largest and bloodiest battle of the Civil War, at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Casualties have been estimated at more than 51,000, including 7,863 dead.

Yet as devastating as those numbers were, only one civilian was killed as a direct result of the fighting: Jennie Wade, a brave, kind-hearted young woman who had the misfortune of being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

She was born Mary Virginia Wade (“Ginnie” to family and friends) in 1843, but because of a newspaper article which misspelled her name, she would come to be known to the world as Jennie.

Like many women during the war, the twenty-year-old and her mother, Mrs. Mary Wade, were left fending for themselves, working as seamstresses to earn a living. For additional income they also took on the role of caregivers during the week to a six-year-old disabled boy named Isaac Brinkerhoff, while his own mother worked away from home.

Jennie’s father, however, wasn’t off fighting the Confederates. A former tailor, with a knack for getting into scrapes with the law (embezzlement being among his misdeeds), James Wade had been declared legally insane and committed to an asylum.

A few days before the Battle of Gettysburg began, as a vanguard of Confederate troops rattled through Gettysburg helping themselves to supplies, Jennie’s sister, Georgiana Wade McClellan, had given birth to her first child, Lewis Kenneth. Mary went to look after Georgiana and the newborn, leaving Isaac in the care of Jennie. The McClellan house was five blocks away, on Baltimore Street. The townsfolk were frightened, but thought that the armies had passed them by.

When the Union Army rolled into town on the evening of June 30th, Jennie became concerned for the safety of her ward and took him to join her mother at the McClellan house. Fighting broke out just a few hundred yards away on July 1, 1863, in what would become the edge of the main battlefield, leaving Jennie and her family caught in the crossfire.

The confrontation continued the following day, with stray bullets and shells shattering windows and damaging the home’s brick exterior. Many of the town’s residents hid in the darkness of their cellars. Jennie, undaunted, ventured outside to offer food and water to the famished Union soldiers.

I’ve Got A Secret – Samuel J. Seymour

On the morning of July 3rd, Jennie was in the pantry of the McClellan house kneading dough to make more bread for the Union soldiers. A flurry of gunfire flew through the air, but all it took was a single bullet to pass through two doors, striking Mary Virginia Wade in the shoulder and penetrating her heart. She died instantly.

Her sister Georgia let out a horrified scream that brought Union soldiers racing into the house. They led the family members to safety in the cellar. Jennie’s body was buried in the backyard of her sister’s home.

On the following day, July 4th, as the Confederate army retreated southward, Jennie’s mother would finish her daughter’s uncompleted task: baking and distributing loaves of bread for the departing Union soldiers.

Six months later, Jennie’s remains were moved to the cemetery of the German Reformed Church. She was praised, deservedly so, as a hero. A Harrisburg newspaper described her as “a lady of most excellent qualities of head and heart.” Not all of the press was positive. Oddly enough, some accused Jennie of being sympathetic to the Confederate cause.

The reason for the allegations is unclear, though some believe her father’s less-than-stellar reputation — along with the fact that she and her sister were named after Southern states — may have fueled the unfavorable talk. A 1917 book, The True Story of ‘Jennie’ Wade: A Gettysburg Maid, put the rumors to rest, branding the malicious gossip as unable to “stand the searchlight of analytical examination, nor the acid tests of proof.”

In November 1865, Jennie’s remains would find a permanent and dignified resting place at Gettysburg Evergreen Cemetery. A monument, reading Killed July 3, 1863 While Making Bread For The Union Soldiers, marks her grave, as does an American flag flown day and night — a patriotic honor she shares with Betsy Ross.

A short distance from the grave lies Corporal Johnston Hastings Skelly Jr., a Union soldier who was engaged to Jennie at the time of her death. In another cruel twist of fate, Skelley, who had been wounded and captured at the Battle of Winchester in Virginia, tried reaching out to his fiancé through Wesley Culp, a childhood friend who was now a Confederate soldier.

Read another story from us: The Mass Exodus of Confederates to Brazil after the Civil War

Culp, however, would be killed in Gettysburg before he could deliver the message. Skelly would die on July 12, before news of Jennie could reach him. Neither would learn of the other’s death.

Barbara Stepko is a New Jersey-based freelance editor and writer who has contributed to AARP magazine and the Wall Street Journal.