In 1918, as the devastating conflict of World War One was close to winding down, an epidemic began that would kill more people than the war itself. Known as the Spanish Flu, it quickly spread and engulfed much of the planet.

It isn’t known exactly where the deadly influenza virus came from. However, the first reported cases were at a military base in the United States in early 1918.

America had recently entered the Great War on the Allied side. Thousands of soldiers were being housed together and then sent off to Europe to fight.

Although the pandemic did not originate in Spain, there is a reason it was given the name. Most countries of North America and Europe were at war and the news outlets in these nations were censored by authorities.

However, Spain was neutral and allowed news of the spreading virus to circulate freely. The casualties in Spain from the flu were also higher than the rest of Europe. Mistakenly, many people assumed that this particular strain began in Spain and the name stuck.

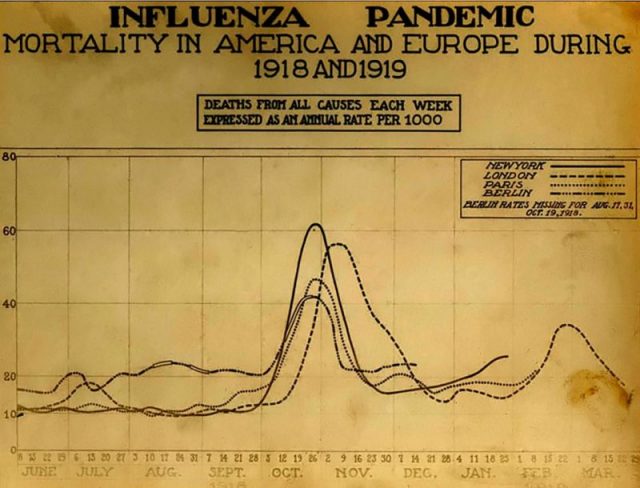

Beginning in a mild form early in 1918, by the autumn of that year the strain had taken a severe and deadly turn. Unlike other common influenzas, which tended to affect the young and the elderly, the Spanish flu hit people between 20 and 40 years old particularly hard. This was especially disruptive as it hit adults caring for young children, leaving thousands orphaned.

Asia and Africa suffered the highest rates of death. Cities were affected more than rural areas. Men tended to be more susceptible than women. The poor, ethnic minorities, and immigrants were more likely to be infected.

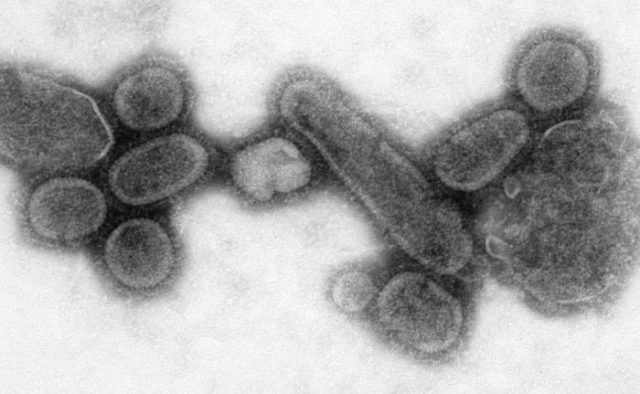

In the 19th century, scientists had gained further knowledge about bacteria. As a result, societies were starting to improve health and sanitary conditions in many parts of the world. It was thought that the latest flu outbreak was caused by germs. But the understanding of diseases spread by a virus such as influenza was still relatively new and misunderstood.

People around the world turned to various rituals to try to stop the dying. There were mass prayer gatherings in Europe despite warnings that crowds of people together would spread the influenza. In some rural parts of China, models of dragons were paraded through streets to scare away evil spirits.

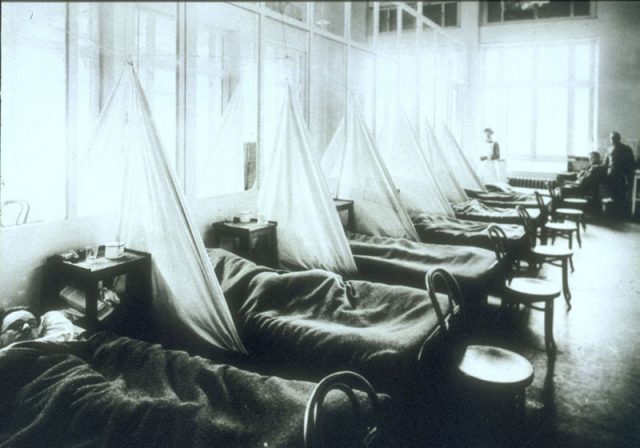

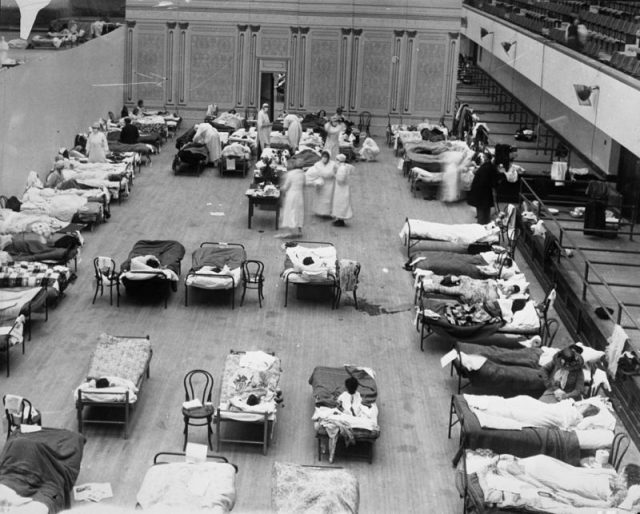

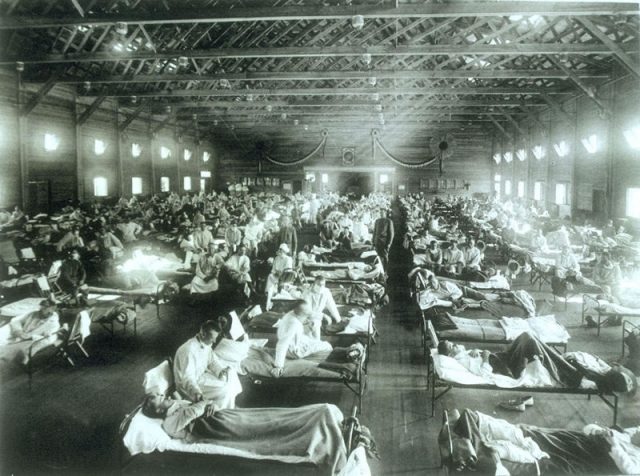

Despite the lack of understanding of what caused the Spanish flu and with no vaccines available, governments around the world mobilized against it. Quarantine areas were established for the sick. Large gatherings of people were prohibited. Some measures may have slowed the spread of the virus. Australia kept quarantine facilities at all points of entry, limiting the effects of the worst waves of the flu.

Despite preventative measures, the Spanish flu was a catastrophe. Up to one-third of the world’s population at the time was infected, an estimated 500 million people. It’s estimated that up to 50 million likely died from the pandemic, maybe more.

Individual suffering was horrendous. After developing typical flu-like symptoms such as coughing and fever, the victim’s skin would turn blue and their lungs filled with fluid, leading to suffocation. Death would often occur just hours or days after developing symptoms. In 1918, the average life expectancy of Americans dropped by 12 years.

The effects on societies were also devastating. Along with the aftermath of years of war, the Spanish flu further disrupted economies and governments that were already struggling. The autumn of 1918 witnessed the rise of workers’ strikes and anti-government protests around the globe.

Parts of Europe were on the brink of civil war. In India, up to 18 million died in the pandemic. The suffering increased agitation against the colonial British lack of response to the crisis, spreading the growing independence movement.

Read another story from us: The Human Remains of Skeleton Lake – Visible Only when the Ice Melts

By the summer of 1919, the Spanish flu pandemic effectively came to an end. In 2008, scientists made a discovery on what made the 1918 virus so deadly. According to researchers, there were three genes affected by the Spanish flu that weakened a victim’s bronchial tubes and lungs. That opened the way for pneumonia to set in and become fatal.