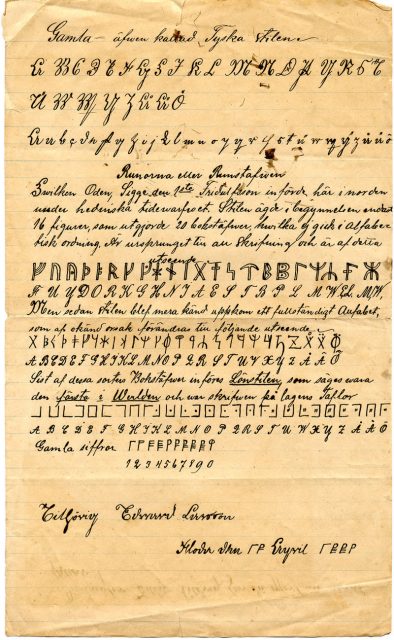

For about eight hundred years, Scandinavians carved and erected stone monuments to their achievements, family members (dead and alive), property and beliefs. These “runestones” were erected throughout the region between the 4th century AD and the end of the Viking Age in the 12th century AD.

That means they were carved for about three hundred years before the Viking onslaught on Europe and Russia and approximately one hundred years after the traditional pagan Viking territories were Christianized.

Most of the runestones known to us today stand in Sweden (approx. 2,000), with others in lesser amounts in Denmark (250), Norway (50), and the British Isles (approx. 40). There was even a runestone discovered on Berezan Island in the Dnieper River in Ukraine, which was a trade route for the Swedish Vikings in the east. Surprisingly, there are no known Viking Age runestones on Iceland.

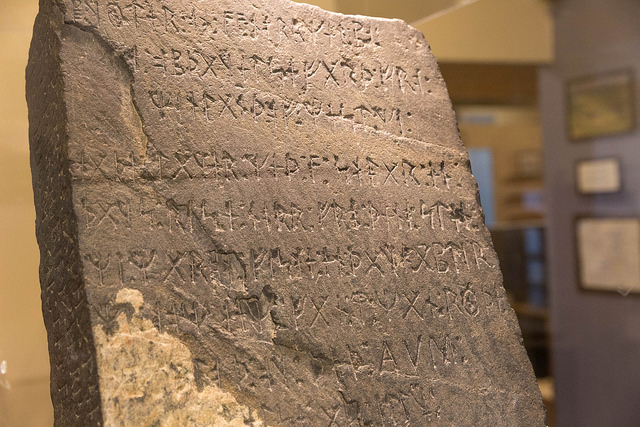

Some of the runestones are complete, others are not – damaged by time, weather or enemies, we only know bits and pieces of what they are trying to tell us. To many, the runestones are not quite a mystery, but have a mystery about them – in a pre-literate society, they mostly tell us little of people’s lives other than what we can piece together from other known facts.

To many Viking Age historians both professional and amateur, the most mysterious runestone is the “Kensington Runestone”. At first glance, one might believe this refers to Kensington, England. After all, the Vikings did raid and possess much of England before 1066.

However, this Kensington is in Minnesota, USA, over 2,700 miles away from L’anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, Canada, the only place in the Western Hemisphere recognized as a landing site for Norse adventurers during the Viking Age.

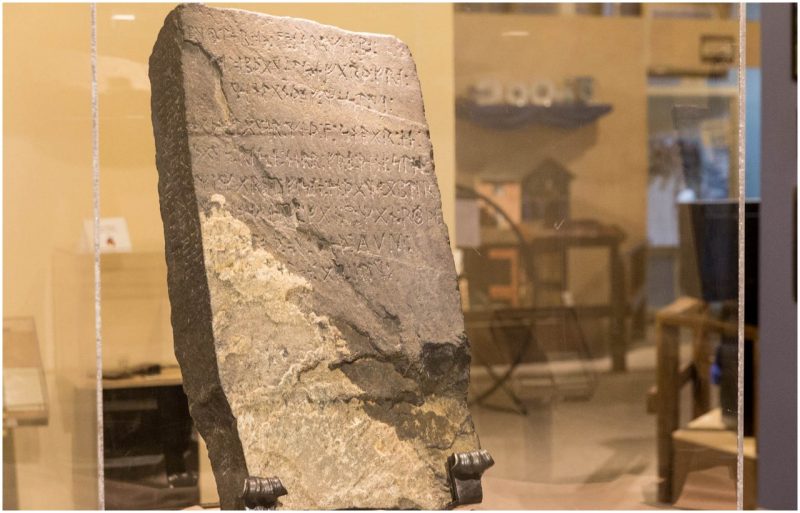

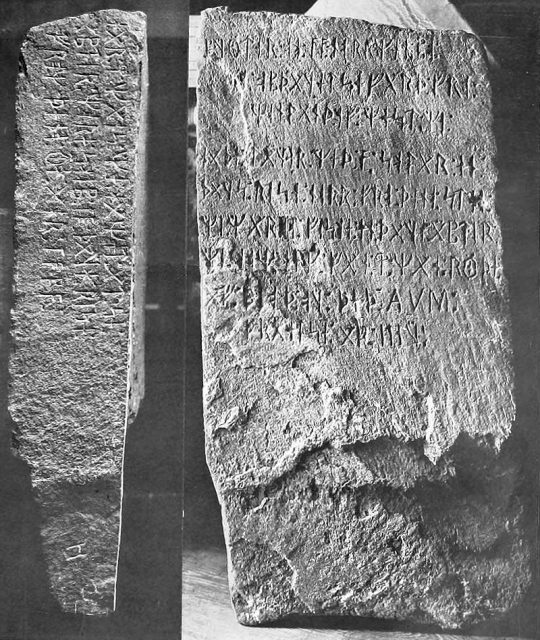

In 1898, Swedish immigrant Olof Ohman announced that he had discovered a type of sandstone stele (memorial) while clearing his land near the town of Solem, Minnesota. He brought the two hundred plus pound stone to nearby Kensington (hence the name), and the local bank put in on display, no questions asked, though a trace paper sketch of the runic characters on the stone was sent to the University of Minnesota.

The translation read as follows (though in the intervening time while some have changed a word or two of the translation with more thorough knowledge of the runes, it remains relatively unchanged): “Eight Götlanders and 22 Norwegians on reclaiming/acquisition journey far west from Vinland. We had a camp by two shelters one day’s journey north from this stone. We were fishing one day.

After we came home we found 10 men red with blood and death. Ave Maria (actually, the runes carved read “AVM”). Save from evil. … have ten men by the sea to look after our ships, fourteen days’ travel from this island. year 1362.”

Initially, many wanted to claim that this was indeed a true Scandinavian object – that some Swedes from Götland and some Norwegians had made it to the American midwest one hundred some odd years before Columbus entered the Western Hemisphere.

It seems odd that the stone would would be found by a none other than a Swedish immigrant at a time when Scandinavian immigrants were flooding into the area.

Viking treasures discovered

Like many other immigrant groups, the Scandinavians were eager to show that they belonged in their new chosen land – how better to claim that than to show that people from their homeland were there hundreds of years before the British?

Also not to be forgotten is that in Europe and in some places in American highbrow culture, Norse/Viking myth and heritage was going through a renaissance of sorts. Wagner had written and performed his “Ring Cycle” in the late 1800s.

Norwegian archaeologists had discovered the Oseberg Viking ship in 1904, the Gokstad ship in 1879, and other archaeological finds seemed to be made yearly. It was a great time to be a Viking historian. It seems quite convenient that Olof found his stone at just this time in history. Still, it should be remembered that Ohman (a farmer) swore to his dying day that the stone was real, and he suffered ridicule and family tragedy because of the notoriety his story caused.

Still, the rock looked aged, the runes looked good, and the message itself was typical of runestones – informational, but still cryptic. It did not say anything such as “We claim this land, etc.”, which would have been a giveaway – no runestones were that literal, and the runic alphabet does not lend itself to detail.

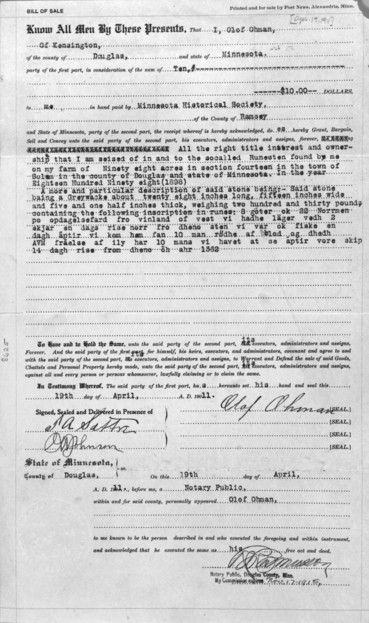

In 1911, Ohman sold the stone to the Minnesota Historical Society for $10, Norwegian historian Hjalmar Holand claimed Ohman sold it to him. Long story short, Holand took the stone to Europe for analysis. Though there was keen debate over the stone’s authenticity, the majority agreed that the text on the front was written in 19th century Swedish, rather than 14th.

Still, there were others, such as a scientist at the Minnesota Historical Society that subjected the stone to the weathering tests of the time (not quite the most accurate system), and he determined that the writing was 500 years old. This announcement brought forth more believers in the authenticity of the stone – mostly among the Scandinavian community in the Midwest.

Twenty years later, more advanced tests were done on the area in which Ohman had found the stone – it had been submerged 500 years previously. No one was doing any writing on a stone at that spot in 1362.

Read another story from us: Only the Strong Survive: Did Vikings Abandon their Sick Children?

The origin of the the Kensington Runestone is still a mystery, however. No one knows who made it and exactly why the hoax was perpetrated.

Matthew Gaskill holds an MA in European History and writes on a variety of topics from the Medieval World to WWII to genealogy and more. A former educator, he values curiosity and diligent research. He is the author of many best-selling Kindle works on Amazon.