Animals were never strangers to warfare. From ancient times horses, elephants and dogs saw wide use in combat, assuming important roles which were often crucial in achieving victories on the battlefield.

As centuries passed and weapons progressed, animals still remained key components in issues like transport and communication.

During WWII, governments of major belligerents in the conflict financed some odd projects that involved using animals as weapons ― from Soviet explosive-packed dogs that were to storm enemy tanks and trenches, to the U.S. bat-bombs, packed with bats each equipped with an incendiary device intended to start random wildfires across enemy territory.

The British also planned to use rat carcasses that had plastic explosive sewn into them and plant them in locomotives so that the driver would mistakenly throw a rat into the train’s boiler, causing a massive explosion.

This plan, together with many others, was never actually applied to the field of battle.

However, the interest in using animals in combat during the Second World War inspired American psychologist and one of the pioneers of behaviorism, B. F. Skinner, to turn to pigeons as means of providing the Allies with a more accurate bomb which would use guidance to hit its target.

Needless to say that during the bombing raids in WWII, numerous bombs went to waste as their accuracy was highly unreliable.

Skinner was known to use pigeons from his earlier experiments related to psychology, and in this case, he believed he could train them to serve as guided-bomb pilots.

Technology at the time prevented the U.S. scientists creating a functional radar-guided bomb, so Skinner proposed that instead of an electronic device, let a pigeon guide the bomb to its target.

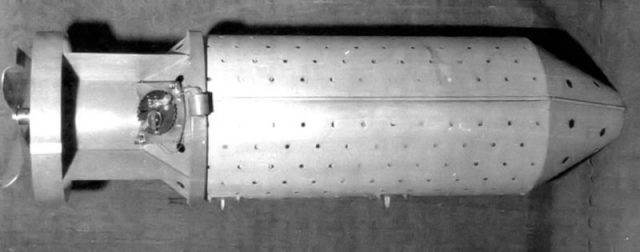

Dubbed as the “Pigeon Project,” Skinners plan involved the unpowered airframe of an earlier prototype developed by the National Bureau of Standards, intended for development of radar-guided bombs.

The bomb was shaped like a small glider and included wings and tail surfaces. In the center of the device, there was an explosive warhead section and a “guidance section” in the nose cone.

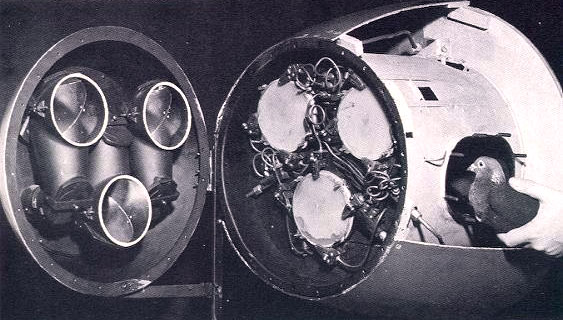

The entrapment was to function using the following principle: one to three pigeons placed in the guidance section of the bomb were faced with a screen mounted on pivots.

On the other side of the screen were three lenses mounted in the nose. Their role was to project the image of the target onto the screen.

The screen was fitted with sensors which measure angular movement, and the pigeons were trained to peck their beaks on the image of the target.

If the bomb went off course, the image on the screen based on pivots would move also. The pigeons would follow by pecking on the screen, as the image went further to one of the corners of the screen.

U.S. Army Air Corps flight school (1936)

The pecking would cause the sensors to recognize the signal and send information to the wings and tail surfaces, which would commence steering the bomb in the same direction in which the screen inside the nose cone had moved, thus returning it back to course.

The movement would cause the screen to return to its central position, urging the pigeons to continue pecking on the image of the target, further correcting any deviation in the course.

Apart from masterminding the entire idea, Skinner’s main role was to use operational conditioning to train the pigeon to peck at the image.

The principle itself was basically an analog version of early electronic guidance systems in which electric signals performed the role of the birds ― detecting the target and preventing deviation from the course.

Even though in theory the plan could work, Skinner noted that the main problem of the project was that no one took the idea seriously enough.

Only a mention of pigeons would cause laughter among the members of the National Defense Research Committee board, who saw the project as eccentric, even for wartime conditions.

Nevertheless, Skinner received $25,000 to fund his project and reportedly made progress in training the pigeons. However, by 1944 the “Bat” radar-guided glide bomb was developed and successfully tested.

This derailed further research in creating “pigeon-guided bombs” as the military canceled the project on October 8, 1944, providing the following explanation:

“Further prosecution of this project would seriously delay others which in the minds of the Division have a more immediate promise of combat application.”

Read another story from us: Why passenger pigeons become extinct

For a short while, the project was reactivated in 1948, under the codename Project Orcon, only to be canceled again, as the electronic guidance systems took the missile technology into a new era of development.

Nikola Budanovic is a freelance journalist who has worked for various media outlets such as Vice, War History Online, The Vintage News, and Taste of Cinema. His main areas of interest are history, particularly military history, literature and film.