Karma, the doctrine of inevitable consequence. The universal principle of retributive justice determining one person’s state of affairs.

King Charles II of Navarre, infamously deemed “The Bad One” for his countless malicious wrongdoings, was a two-faced treacherous human being whose duplicitous dealings and constant scheming led him to realize the faithfulness of this doctrine probably better than anyone else.

But let us roll back in time and see how karma caught up with Charles, the curious individual whose life stands to prove that men are sometimes not punished for their sins, but by them.

Charles II, born Carlos El Malo in Évreux, Normandy, to Philip III, Count of Évreux, and Jeanne, the only surviving child of Louise X, the king of France and Navarre, carried a grudge against the crown of France for as long as he could remember.

His mother should have been next in line to the throne when her father died in 1316. Except she was denied this right for she was not a man, and the crown went to her uncle, Philip de Valois, or Philip “The Tall” who allegedly first poisoned his own nephew, John I Posthumous, and then loudly advocated that French tradition excluded women from the line of succession.

As the closest male heir in line and backed by the French Lords who were not so eager to be ruled by a woman, Philip was crowned King of France and Navarre the same year in November.

To sweeten things up, he awarded lands in Champagne and Brie in the north-east of France to his niece Jeanne — provided she married Philip II of Évreux and denounced her rights to the throne.

When he died 6 years later, however, the Navarrese people pledged allegiance to Jeanne instead of giving it to Philip’s successor, his brother Charles IV who inherited the crown in 1322.

Carlos, born a decade later on October 10, 1332, found himself in a complicated state of affairs from birth, raised with the notion that when he grew up, he would succeed his mother, inherit the lands of his father in Normandy, and as a direct descendant to King Louis X, rightfully sit on the throne of France.

This was not the case, however. When his mother died and he was crowned King of Navarre in 1349, his right to claim the throne of France was dismissed. According to the same rules and traditions that excluded his mother from any rights of inheritance, he also couldn’t inherit the French crown because he came from a king’s daughter, not a king’s son.

To make things even worse, by this time, his mother’s lands in north-eastern France had been taken away from her.

So you could see why a boy with crushed hopes, full of wrath, raised by a mother who due to her sex was wrongfully cast aside, dedicated his whole life to right the wrongs that had been done to his family and reclaim everything he thought was rightfully his. He was craving for revenge.

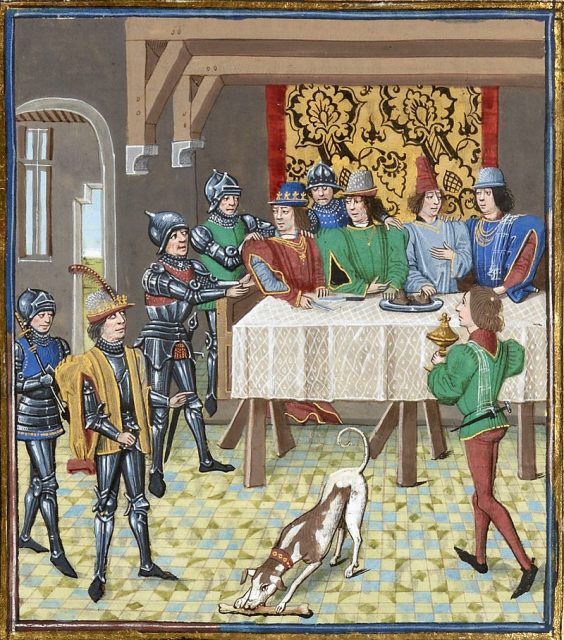

Philip’s son, John II, better known as “John the Good,” who was crowned King of France instead of him almost instantly proposed a union between his daughter Joan and Charles II. But while “the Good” king believed the union would be a move in the right direction for the two kingdoms and a small but vital step towards reconciliation, “the Bad” one saw something else in it besides that.

Charles married Joan in 1352 but, being well aware that France had ongoing problems with England and King Edward III (a conflict that would later be labeled the “Hundred Years’ War”), he tried to squeeze a sweet deal out of his father in law and asked for Champagne and Brie to be returned to him. But John had already given them to his favorite constable Charles de la Cerda and was not willing to change his mind for the time being.

Shortly after the king’s decline, La Cerda was assassinated, with Charles stepping up to take the blame, coolly admitting to the crime as if it was nothing. To add insult to injury, King John II learned his son-in-law bragged about it to King Edward’s closest associates in an attempt to get him on his side. From then on all chances for a real truce were lost between the two kings, but still, John opted to appease his murderous son-in-law, fearful he might switch sides.

John gave him land in Normandy, however Charles betrayed his trust and plotted with the English king nonetheless.

Upon learning about his treacherous plans, John had had enough. Charles was imprisoned in Ruen in 1356 from where he escaped, but by the time he did, the kings of France and England already found grounds for peaceful negotiations.

He opened up the gates from the prison for every prisoner to escape, asking them to wreak havoc through the streets of Paris in return. Wile John was almost sure that it was the English who did it, Charles went behind his back to the king of England and, once again, offered allegiance to him on condition that they share the spoils if Edward officially recognized him as the rightful ruler of France.

In the meantime, he and John made peace again. There was a peasant’s uprising in France against the Lords in 1358, which Charles first supported in secrecy to gain the trust of the commoners, then switched sides and helped the French aristocracy to suppress the revolt.

He arranged a meeting with the peasant leader, whose trust he already had, for truce talks but had him tortured and beheaded when he arrived. A lot of peasants were slaughtered and burned without remorse on his orders during the suppression later on.

Historic Noblemen and their ridiculous nicknames

His double-crossing and double dealings with both France and England went on and on until both John and Edward finally saw right through him. Charles was then forced to return to Navarre and seek other allies or another alternative to achieve his goals. Short of allies, he tried invading France himself. It didn’t work.

He lost his lands in Normandy and the trust of the French Lords. He meddled in Spanish affairs and lost everything in France because of it, forced to pay a great deal of money to the Spanish King.

Finally he tried twice, in 1369 and 1370, to poison Charles V, the King of France, and the son of his longtime ally-enemy John II, “The Good.”

Without any help either from the English nor from France, in 1379 his kingdom was sacked and Charles had to surrender 20 fortresses just to keep his status as king over what was left of Navarre after Castilian garrisons rampaged through his homeland.

Charles lost the respect of everyone, even his own people. By that time, the Navarrese were fed up with their kings incompetence and the word “Bad” was attributed to him, not for his heinous acts but merely because he was bad at making decisions. They didn’t hate him per se, but let’s say if he was burning and they had water at hand, they’d probably drink it. Which is precisely what happened, figuratively.

If the stories are to be believed, ill-struck Charles was confined to his bed in Pamplona on New Year’s Eve in 1386, wrapped up like a cocoon in linen, soaked in distilled wine, or aqua vitae to keep his temperature at bay as per doctors instructions.

He was to be sewn into it at bedtime and let the alleged healing powers of the alcohol do the trick overnight. When the maid, acting as an in-house nurse finished wrapping him up, there were no scissors around to cut the thread, and her king was yelling at her to hurry up and be done with it. So she used the candle standing nearby.

The alcohol-soaked king went up flames in an instant, and the maid not knowing what to do allegedly ran away petrified, leaving her king to burn to death right after midnight on January 1, 1387.

Read another story from us: King Frederick the Great was a Runaway Teen

Most likely, Charles, surrounded by so many who wanted him dead, was assassinated, but there wasn’t any proof left behind. Anyway, most preferred this story. The story about the bad king who, as the saying goes, played with fire all of his life, and got burned to a crisp at the end. A just end, for an unjust human being.