It is a relatively common misconception that people in the Middle Ages did not bathe regularly, if at all. However, baths and bathing were, in fact, quite common during the medieval period.

The Middle Ages, or Medieval period, spans roughly between the fall of the Roman Empire and the Renaissance (roughly 476 – 1450 AD). The early Middle Ages are sometimes referred to as the Dark Ages. During this era, society was split up into roughly four parts: nobles, non-nobles, clergy, and non-Christians. During the later Middle Ages, the working class and middle class were added into the group of non-nobles.

Each section of society practiced bathing habits and personal cleanliness at different levels as well. Naturally, manual laborers and the poorest members of society were at the lower end of the hygiene scale.

Without access to large tubs in which to immerse themselves, or perhaps even fuel to heat water (it was needed for essentials, like cooking and staying warm), bathing was largely limited to the summer months, when a refreshing dip in a pond or stream would do the trick after a hot day in the fields. Nonetheless, they likely practiced a regular wash down of sorts, even with cold water or a damp cloth.

The Romans had built several public bathhouses throughout their empire, including the famous one in the eponymous town of Bath, England. Many of these survived, at least in part, and several more were established, which the general public in the Middle Ages could use to get clean. In Southward alone, across the Thames from London, one had the choice of 18 different hot baths.

However, since bathhouses also had a reputation for being less than respectful, they were often condemned by the church, which had a strong hold over the daily lives of all members of medieval society. That did not stop them from being used altogether, however.

In the church itself, the rules and practices varied greatly, with some monastic orders supporting regular washing and others not so much. For example, the monks of Westminster Abbey were only required to bathe four times a year – Christmas, Easter, June and September – although it is likely that these were the only obligatory days, as the monastery did employ a bath-attendant whose services were used regularly, according to records. According to the rule of St. Caesarius, from the beginning of the 6th century, nuns and monks were expected to bathe regularly.

This included washing ones face and hands, as well as brushing one’s hair, and keeping teeth “picked, cleansed, and brushed.” The church did not approve of “excessive” bathing, however.

For those in the medieval Holy Lands, bathing traditions came from those of Greece, Rome, Egypt and Arabia. Public bathhouses included hot rooms for sweating and steaming, and cold rooms for washing off. Massages with scented oils were not uncommon either.

Surprising Origins Of Popular English Phrases

Crusaders adopted these practices happily, and even built their own baths, including those at the Hospitaller and Templar headquarters in Jerusalem, as well as on Mount Zion at Atlit, and several others. Turkish-style bath houses remain a popular attraction today, even in cities outside of Turkey, such as Budapest.

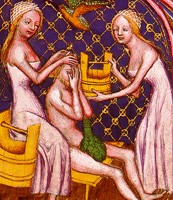

Nobles could afford a private bath, and it would often take the form of a large wooden bathtub, sometimes with a curtain around it, or a tent-like cloth over top. Servants would fill it with jug after jug of hot water, and sometimes scent the water with herbs and flowers.

Records from the Middle Ages indicate that some kings really enjoyed their baths. According to BBC, King John traveled with his bathtub and tub attendant. And Edward III had taps of hot and cold water for his bathtub in Westminster Palace.

And as recorded by his biographer, Einhard, King Charlemagne “would invite not only his sons to bathe with him, but his nobles and friends as well, and occasionally even a crowd of attendants and bodyguards, so that sometimes a hundred men or more would be in the water together.”

While the often-portrayed view of the filthy, medieval person may not be entirely true, it certainly wasn’t easy to have a regular bath in the Middle Ages, and hot water was definitely not as convenient as today.

Nonetheless, the people in the Middle Ages appreciated personal hygiene at least on some level, and tried to attain it as best that resources would allow. Whether by simply keeping their hands and face relatively clean, as well as their clothing, medieval people were not afraid of bathing, nor was it considered a sin. It just was not as simple as turning a tap.

Patricia Grimshaw is a self-professed museum nerd, with an equal interest in both medieval and military history. She received a BA (Hons) from Queen’s University in Medieval History, and an MA in War Studies from the Royal Military College of Canada, and completed a Master of Museum Studies at the University of Toronto before beginning her museum career.