Marilyn and Liz: In the Hollywood of the Fifties and Sixties, no female movie stars were bigger.

Though they were total opposites in the looks department — Elizabeth Taylor, a sultry, finely-chiseled, raven-haired brunette; Marilyn Monroe, a luminous, wide-eyed, childlike blonde — they had much in common, including much-publicized marriages, headline-grabbing scandals, and high-maintenance personalities.

Though their paths rarely crossed (Liz worked at MGM, while Marilyn was the face of Twentieth Century Fox), in 1962, their lives would intersect in a big way.

For decades, motion pictures were king, but when the fifties came along, things were changing. For one thing, the Supreme Court put an end to studio-owned theater monopolies in 1948, which took a big bite out of profits.

What’s more, a new invention — television — kept people home, watching the likes of Lucille Ball and Milton Berle, and out of the theaters. In order to survive, studios had to find ways to make money — fast.

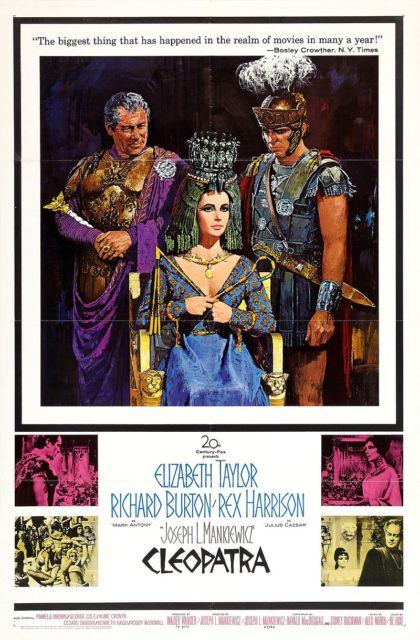

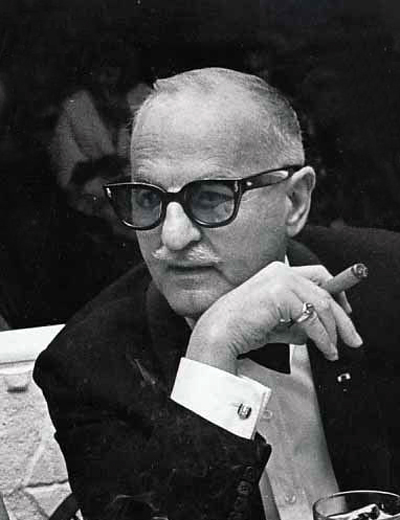

Fox producer Walter Wanger hatched a plan to bring people back to the theaters: an epic to end all epics. And he had just the big-screen spectacle in mind: Cleopatra.

After all, movies based on the Egyptian queen’s life, starring Claudette Colbert in 1934 and Vivian Leigh in 1945, had done well in past.

And who better to play the seductress this time around than Elizabeth Taylor, who was recently released from her MGM contract and free to work at other studios? Bonus: Liz’s new-found notoriety as a brazen home-wrecker — stealing Eddie Fisher from his wholesome wife Debbie Reynolds — might be just the thing to bring in curious moviegoers.

Taylor needed some convincing, so the studio made her an offer she couldn’t refuse: a $1,000,000 salary, making her the highest-paid performer at the time. A hefty sum, to be sure, but the studio figured they would recoup the money — and more. And then the headaches began.

From the start, the production, which began in September 1960 at London’s Pinewood Studios, was beset with questionable decision-making and spiraling-out-of-control costs. Taylor would make 65 costume changes in the film (earning her a place in the Guinness Book of World Records).

Constant rain (this being England, after all) caused pure gold leaf, meticulously applied to the sets, to peel. Re-writes left hundreds of extras just sitting around, though still picking up paychecks.

At this point, Cleopatra was costing $70,000 a day to make. Then, in March of the following year, Taylor came down with pneumonia, needing a tracheotomy to save her life.

When it was decided that the cold, damp English weather wasn’t conducive to her fragile health, the Pinewood sets were torn down and rebuilt in Rome, at an astronomical cost.

Glamorous Hollywood leading Ladies Quotes

Fox was hemorrhaging money and studio execs were freaking out. However, they had come too far to shut things down.

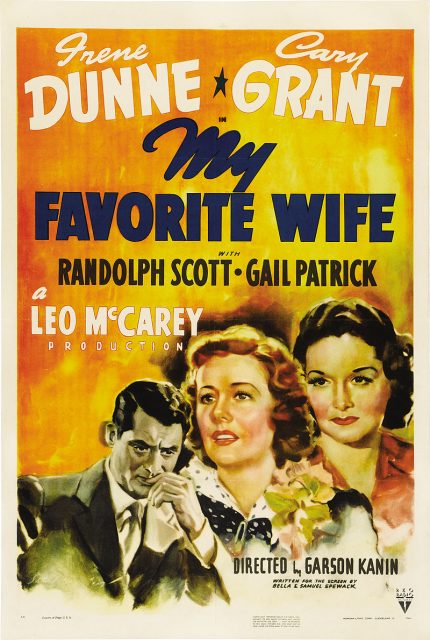

Then Fox hatched another plan. What was needed was a movie that could be made quickly (and on a dime) — with the profits used to help recoup the staggering losses from Cleopatra. They decided on remake of My Favorite Wife, a 1940 comedy starring Irene Dunne and Cary Grant — refashioned for Marilyn Monroe and Dean Martin.

Monroe didn’t exactly love the script — yet another (sigh) frothy role. Nor was she thrilled that she — Fox’s most famous star — would be making a paltry $100,000 salary, one-tenth of Liz’s take for Cleopatra. But Marilyn, a sex symbol staring down the barrel of her thirty-sixth birthday, wanted to show studio execs (and the world) that she still had it.

The cameras starting rolling on Something’s Got to Give in April 1962 — and from the get-go, there were problems. On the first day of production, Monroe called in sick, claiming she had a severe sinus infection and couldn’t work.

The movie was postponed for a month and director George Cukor was forced to shoot around her, putting the production behind schedule and over budget.

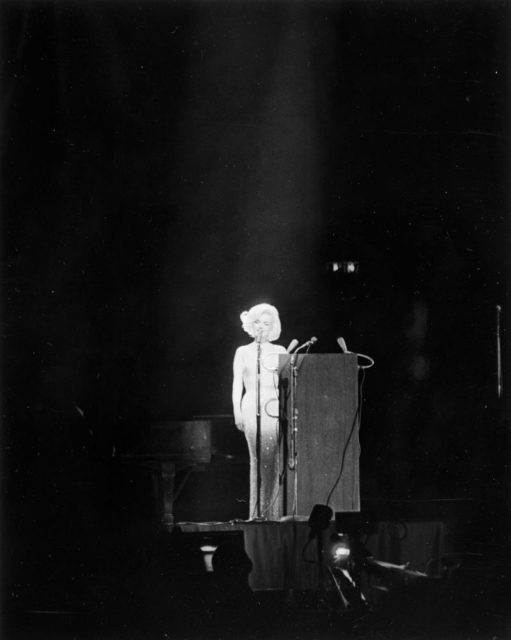

But what really sent everyone over the edge: Weeks later, Monroe skipped out on filming once again, yet still managed to appear at a May 19th gala at Madison Square Garden for President Kennedy’s birthday, singing a seductive rendition of “Happy Birthday.”

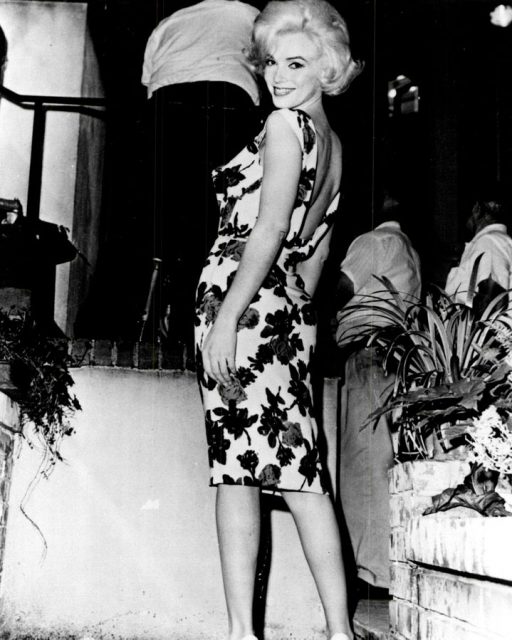

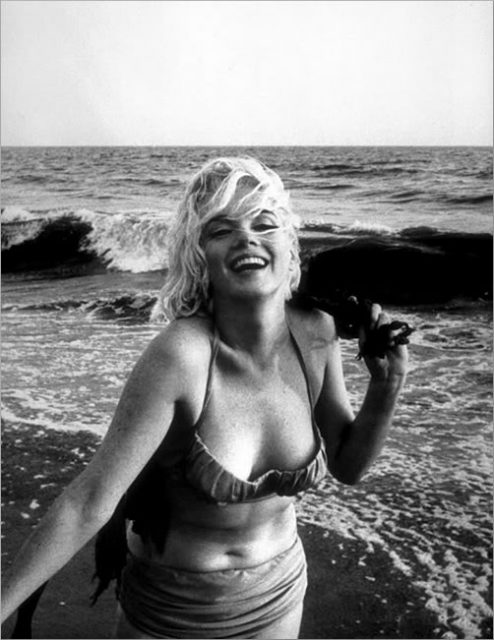

Upon her return, Marilyn decided to give the movie some buzz, as only she could — with a nude swimming scene.

When filming for the day was finished, photographers, invited by Marilyn, were let onto the set to snap away, as the actress posed, first in a flesh-toned bikini bottom, then without it — a provocative move back in the day. The photos would show up in publications around the world, and Marilyn said she was delighted “to get Liz Taylor off the magazine covers.”

The actress celebrated her 36th birthday on June 1st with a party on the set. That evening, she went to a fundraiser at Dodger Stadium. L.A. was uncharacteristically chilly that night and Marilyn’s health would take another hit. She was unable to report to work the following day. This time, studio execs had enough: On June 8th, she was fired.

Though Monroe may have been a headache, ultimately, the decision to close down her movie may have been a result of the progress (or lack thereof) of Fox’s Cleopatra — still in production, still bleeding green.

The studio didn’t have the money to keep both projects running, and since they had invested so much into Cleopatra, Monroe’s movie was the one to be shut down. Ironically, Liz had been just as much of a headache as Marilyn — showing up late and delaying production because of various illnesses.

And then, there were the over-the-top extravagances — like having Liz’s favorite chili flown in from Chasen’s, a favorite West Hollywood haunt, all on the studio’s dime.

Still, the studio went into attack mode, blaming Monroe’s “unprofessional” behavior for her film’s demise. But the actress wasn’t going down without a fight. She launched her own publicity campaign to get out her side of the story and enlisted the help of Fox honcho Darryl F. Zanuck.

The studio re-hired her, agreeing to pay her more than her previous salary of $100,000. Filming was set to resume in October, but Marilyn would die of an overdose on August 5th.

Cleopatra wrapped on July 28, 1962. Movie-goers came, but it would take years for Fox to see a profit, selling the broadcast rights to television. Meanwhile, the studio revamped Something’s Got to Give as the 1963 comedy Move Over, Darling, with Doris Day in the staring role.

Liz would go on to marry her Cleopatra leading man, Richard Burton, and nab a second Oscar for 1966’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

Read another story from us: Joe DiMaggio and the Mysterious End of Marilyn Monroe

But Marilyn may ultimately have won the battle of the big-screen legends by acquiring icon status in death — something that didn’t sit well with Liz, who would tell British journalist Peter Evans: “Dying young does give Marilyn an edge over most of us. But I nearly died quite a few times. Nearly dying was my specialty. That has to count for something, doesn’t it?”

Barbara Stepko is a New Jersey-based freelance editor and writer who has contributed to AARP magazine and the Wall Street Journal.