On February 10, 1863, the cover of Harper’s Weekly showed Lavinia Warren of Middleborough, Massachusetts, getting married to Charles Stratton, better known as Tom Thumb.

There were more than 10,000 people attending the wedding in NYC. If you are not familiar with them, well they were rich, famous, and very handsome characters, both with a form of dwarfism.

They became celebrities in the “freaks shows,” in which so-called “monstrosities or marvels of nature” were exposed. To satisfy the public’s taste, the managers of such shows demanded the “freaks” perform some extraordinary feats.

Lavinia Warren came from a very respectable family and worked as a school teacher since she was 16. Then she started working as a miniature dancing chanteuse on a Mississippi showboat.

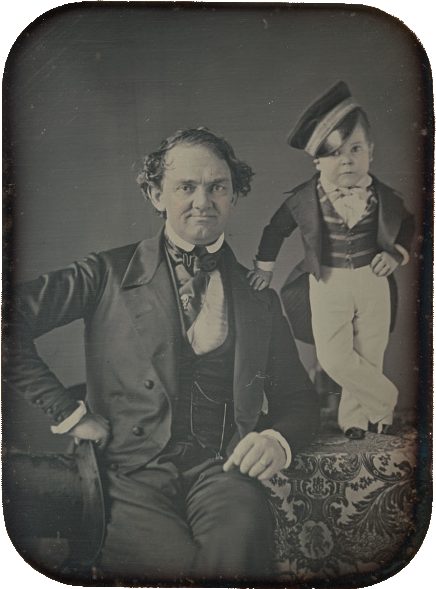

One day in 1862, the famous showman and impresario P.T. Barnum came to meet her. Besides her singing and dancing, Lavinia was very charming and spoke graciously. She fit perfectly at Barnum’s museum for oddities.

The 32-inch-tall Lavinia was a very beautiful and lovable lady. She was called the “Queen of Beauty,” and many co-workers fell for her charm, including Commodore Nutt, a proportionate dwarf just like Lavinia and seven years her junior. But she fell for Charles Stratton, aka General Tom Thumb.

Stratton had worked for P.T. Barnum since the age of 11 when the showman began exhibiting the little person in England. Much to Barnum’s delight, Stratton and Lavinia got romantically involved, and it didn’t take long before he proposed and she accepted.

The wedding ceremony was a greatly publicized event, intentionally made intriguing so that more guests would come. Barnum charged a $75 entrance fee to the 2,000 guests at the extravagant Metropolitan Hotel.

Before the reception at the hotel, the wedding ceremony took place in the fashionable Grace Church on Broadway. There were around 10,000 people who gathered on the streets to see the famous couple. After all, Lavinia and Tom were among the most famous Americans in their time.

Lavinia, with her lavish spending habits for expensive designer clothes and items, purchased her wedding dress from Madame Demorest, one of the most sought-after fashion designers at the time. She created a diminutive-size wedding gown which was put on display for weeks before the wedding.

Minnie Warren, Lavinia’s sister, was the bridesmaid at the wedding while Commodore Nutt, still heads over heels in love with the bride, was the best man.

The newlyweds stood on top of a grand piano to meet the guests. In the media and among the public, the wedding was called “a fairy wedding,” and Barnum succeeded in profiting from it and turning the wedding into the event of the year.

The event was covered by the New York Times and Saturday Evening Post. For the first time in a while, the front pages of the newspapers carried a story about something other than the war. Even the wedding presents were listed in detail: a carriage from Queen Victoria, a miniature billiard table, Tiffany gems, and so on.

“No one need be surprised that two little matters should create such a tremendous hullabaloo, such a furor of excitement, such an intensity of interest,” wrote the New York Times.

Even President Lincoln was eager to meet Lavinia and Tom, so he invited the couple to the White House. However, Lavinia, who always hated people treating and petting her like a child instead of a woman, didn’t hesitate in being unfriendly to the president when Lincoln joked about their height difference.

Lavinia and Tom remained in love for the next twenty years. They lived comfortably, enjoying the lifestyle of high society, socializing with socially eminent figures, and performing part-time at Barnum’s American Museum in New York, or touring with shows.

Tom died in 1883 and Lavinia remarried two years later to another little man, “Count” Primo Magri from Italy. She did so to save herself from loneliness but also from getting penniless – she had poor money sense, spending a lot on luxurious items and not earning as much as before.

She performed along with her second husband in an independent opera company. Lavinia also appeared in one silent movie in 1915, The Lilliputians Courtship.

Read another story from us: The Court Dwarf Served in a Pie to a King

Even though she outlived Tom by 36 years, before her death in 1919, Lavinia requested to be buried alongside her first husband in Bridgeport, Connecticut. The gravestone bears Stratton’s name and a life-size statue of him, while Lavinia is simply marked as “His Wife.”