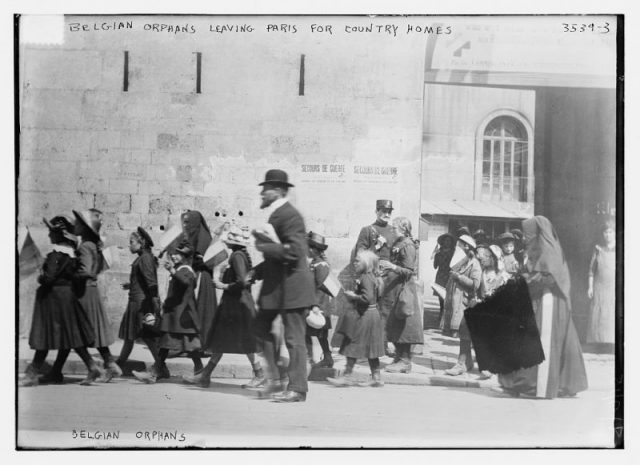

Baby Lottery. Yes, you read that right. In 1911 Paris, would-be parents — not biologically blessed or for whatever reason not being able to have children of their own — could acquire a precious bundle of joy by relying on the luck of the draw. The event was the brainchild of a foundling hospital (basically, a children’s home) as a way to find homes for their littlest orphans.

Though the idea of a “Loterie de Bébés,” as it was called, may seem kind of bizarre — not to mention, more than a little distasteful — when you consider the time in which it was held, the lottery may actually have been a humane idea.

Back in the day, children were considered almost expendable, and those who weren’t taken in by orphanages often faced a dismal fate, like something straight out of a Dickens’ novel: a life on the streets, with many starving or freezing to death during brutal winters.

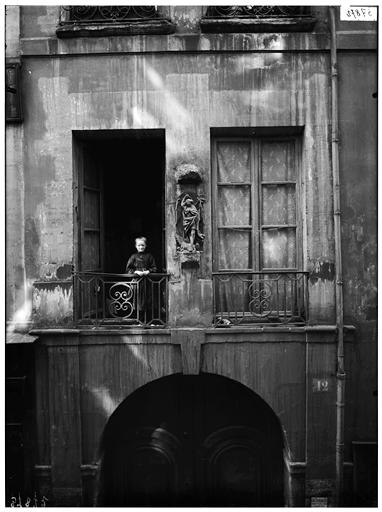

The state-run orphanages created in the 17th and 18th centuries to help save these children were far from ideal.

For one thing, no one was monitoring these institutions to ensure that the children entrusted in their care were being treated well.

In America, the institutions weren’t officially policed until 1912, with the creation of the United States Children’s Bureau. This agency was founded to investigate all aspects of child welfare, such as infant mortality, orphanages, abuse and neglect, and child labor.

I’ve Got A Secret – Samuel J. Seymour

And it wasn’t until the mid-19th century that large cities began finding alternatives for group orphanages — namely, a foster care system and private adoption agencies.

But flawed though these early orphanages may have been, they at least gave abandoned children a fighting chance, in the form of a roof over their heads, a bed, and warm meals.

What’s more, many offered some kind of a training to help the youngsters survive outside in the real world, usually as a mechanics-helper or a domestic servant.

Ultimately, they had better lives than those who ended up in workhouses — slaving away on factory assembly lines, fighting over scraps of food, crammed into beds with other children, or suffering the repercussions from an alarming lack of hygiene.

Some children, at the mercy of drunken adults, were assaulted regularly.

And, as a 1912 article published in Popular Mechanics, of all places, would point out, the Paris Foundling Hospital that devised the baby lottery had its heart in the right place — making sure that the babies were placed with responsible parents and directing dollars made from the event to worthy causes.

Or, as Popular Mechanics put it: “The proceeds of the raffle were divided among several charitable institutions. An investigation of the winners was made, of course, to determine their desirability as foster parents.”

If nothing else, the baby raffle would shine much-needed light on a societal problem that desperately needed to be addressed. And find a place, for a lucky few, to call home.

Barbara Stepko is a New Jersey-based freelance editor and writer who has contributed to AARP magazine and the Wall Street Journal.