Graffiti is not a modern form of expression. People have been leaving their marks, or making comments on their world, on walls for thousands of years.

Graffiti has famously been found in Pompeii, Egyptian pyramids, ancient Chinese caves, and even a Viking church.

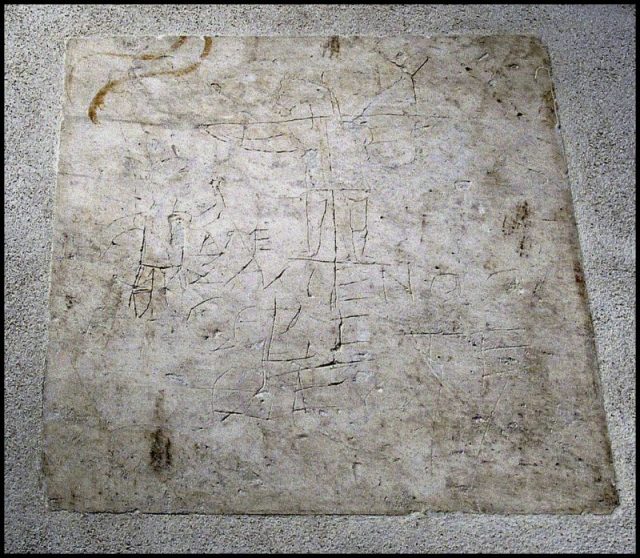

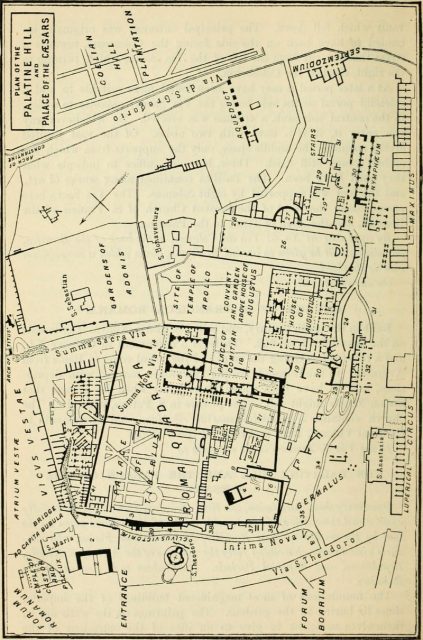

In 1857, however, an excavation on the Palatine Hill in Rome revealed a particularly interesting piece of graffiti on a plaster wall.

Since named the Alexamenos Graffito, it is believed to date from around 200 AD and is possible the earliest surviving depiction of Jesus. And it is not at all flattering.

Along with being one of the oldest surviving representations of Jesus, it may also be one of the earliest depictions of the Crucifixion of Jesus, since the event was only rarely depicted in Christian art before the 6th century.

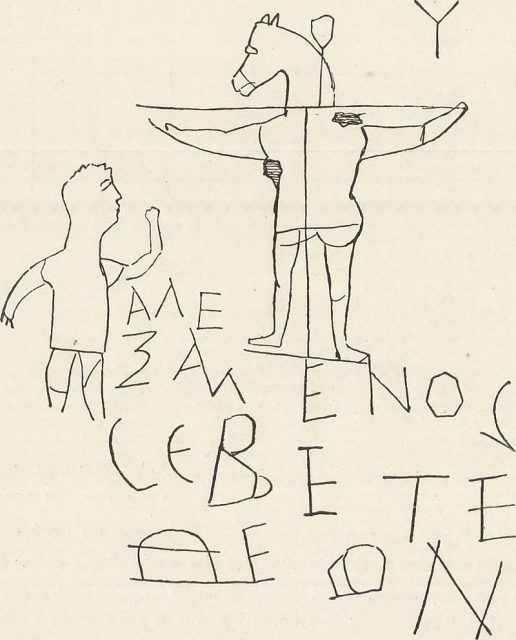

The drawing, scratched crudely into the soft plaster, shows a male person worshiping a figure on a cross, only the figure is wearing has the head of a donkey.

There is an inscription in Greek, “ΑΛΕ ξΑΜΕΝΟϹ ϹΕΒΕΤΕ ϑΕΟΝ”, or “Αλεξαμενος σεβετε θεον” in standard Greek, which translates roughly to “Alexamenos worships his god,” or “Alexamenos worships God” (there are several variations of the translation).

The originator of the graffiti manages to mock both Jesus and Alexamenos at the same time.

The illustration has been interpreted as Alexamenos being a Roman soldier or guard. His left hand is raised in a gesture that is suggests worship.

The Greek letter upsilon or a tau cross is at the top right of the image. There has been no real consensus as to the date of the image, and estimates have ranged from the first to the third century.

The figure on the cross (presumed to be Jesus, although some scholars argue it could be another deity) is as we would think of a modern depiction of Christ Crucified (minus the donkey head).

His arms are outstretched, pinned to the horizontal cross bar. His feet are fixed to a platform on the vertical section of the cross, and he is wearing a garment that covers the lower portion of his body.

With the Jesus figure wearing the head of a donkey, however, it is not farfetched to conclude that this illustration was meant as a mocking portrayal of a Christian performing an act of worship.

During the early Christian period, non-believers (who remained the majority for centuries), ridiculed Christians for worshiping a man who had been crucified – the execution method reserved for the worst criminals until it was abolished in the 4th century by emperor Constantine, a devout converted Christian.

The relationship between Christians and Romans was testy at best for a few centuries, and often changed. Sometimes Christians would be put to death for their beliefs, after being hunted down by Roman authorities.

At other times, they were allowed to (discreetly) worship their God, but they were often still mocked and shamed for it.

Mysterious Ancient Societies That Disappeared

At the time, it was commonly believed that Christians practiced a form of religion called onolatry, or donkey worship.

This came about through the misconception that Jews had worshiped a god in the form of a donkey, as claimed by Apion, an Egyptian grammarian, in the first century BC. Tertullian, an early Christian author, also reported that Christians were accused of worshiping a donkey-headed deity.

The intentions of the author of the graffiti are, and will forever remain, unknown. Did he (or she) mean to simply mock Alexamenos and/or Jesus in relatively harmless way? Or was the purpose to “out” or intimidate Alexamenos?

It may be the latter, as the location of the graffiti is also of interest. It was discovered in the domus Gelotiana, which was a house that had been acquired by the emperor

The wall on which the graffiti was located was not in what would have been a public area, but it would have been visible to many other people in the house. Either way, it likely succeeded in making Alexamenos rather uncomfortable, to say the least.

Read another story from us: Afghanistan’s Amazing Last Buddhist Relics – the Taliban Blew Them Up

When the street where the domus Gelotiana sits was walled off to support extensions to buildings above, the graffiti was hidden and sealed off for hundreds of years. Since the excavation, the piece of wall on which the figure was etched has been removed and is now in the nearby Palatine Hill Museum.

Patricia Grimshaw is a self-professed museum nerd, with an equal interest in both medieval and military history. She received a BA (Hons) from Queen’s University in Medieval History, and an MA in War Studies from the Royal Military College of Canada, and completed a Master of Museum Studies at the University of Toronto before beginning her museum career.