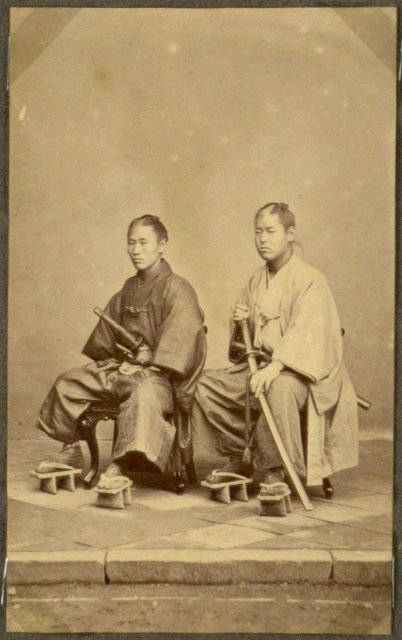

When it comes to the art of deadly swordsmanship, few groups are as respected and feared as the samurai. The elite and historic military of ancient Japanese culture, they are depicted everywhere, from ancient artifacts to modern day movies. One of the most well-known of these is The Last Samurai (2003), which placed a distinctly Hollywood spin on a proud people.

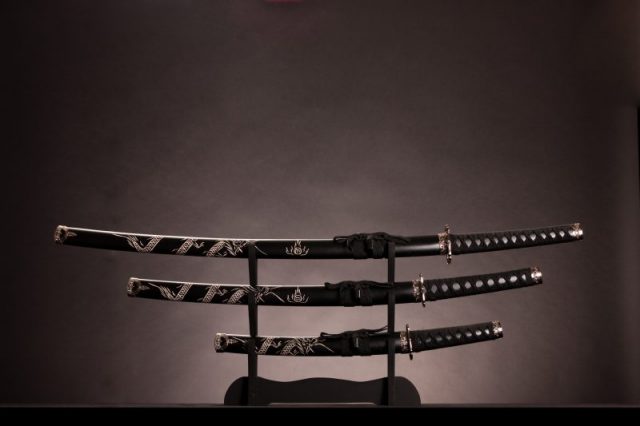

The non-fictionalized reality of samurai life is infinitely more interesting. One sword of choice was the katana. Its use transcended the outward appearance of a tool to slice and dice with.

The website of the V & A Museum details the significance of a sword to the Japanese, stating “Its efficiency is such that it can cut through armour without breaking or bending and its spirituality is imbued by the religious rites involved in its production. The Japanese sword is a terrible and efficient weapon combining a beauty of form with an elegance of function.”

With so much invested in a samurai’s blade, it stood to reason there were strict disciplines to keep a sword in optimum condition. “Tameshigiri,” or “test cut,” was arguably one of the first examples of quality control. Sword owners who wanted to put their gleaming metal to the test found a vigorous and indeed violent way of demonstrating the durability of a weapon.

Though a skilled practitioner’s hands and eyes were essential, the aim of tameshigiri was to put the sword itself through its paces. It was also utilized for budding swordsmen who were still getting to grips with their blades. Practice makes perfect, though in this case perfection could lead to someone losing an ear if they weren’t careful.

The process is still employed today, with its current use more in line with what took place during the late Edo and early Meiji Periods (around the 1800s). This version of tameshigiri is summarized by the website tameshigiri.ca as “testing the sword against the object being cut.”

Take a closer look with this video:

https://youtu.be/tTJ9y-ThNHw

It goes on to say “Under this definition, helmets (kabuto), armour (yoroi), and heavy sections of bamboo or wood might be cut. This testing process, if incorrectly carried out by unskilled practitioners, or where the quality of the blade was not the best, could easily result in the destruction of the sword.”

The katana was a formidable weapon, but it was by no means indestructible and had to be handled with great care and skill. Part of that skill, however, featured seeing how far a sword could go before it finally shattered.

An extreme type of tameshigiri called “aratameshi” pushed a hardy blade to fantastic levels of endurance: “many believe this practice was an attempt by the Japanese to prove the superiority of their weapons over European blades.” Even with a strict code of conduct, it seemed the samurai wanted to show off as much as the next soldier.

There was a more direct method of assessing the sword’s performance in war, a technique that was visceral and quite literally to the point. Go back through history and the reader will find a branch of tameshigiri called “suemonogiri”, meaning “the cutting of tied objects.” As for what those objects were… well, the methods of that bygone era weren’t quite as humane as we see thing today.

They thought that in order for the sword to be fully prepared and ready for real world application it had to have practice with actual deceased human bodies. These were typically criminals, and their corpses provided the ultimate test for any sword.

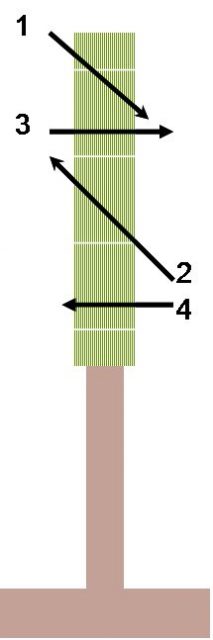

It is noted on tameshigiri.ca that “positioning was important, as the blades would often bisect the deceased’s body along lines designed to cut through the maximum amount of bone possible. It required extreme skill on the part of the tester, who must cut precisely or potentially break the blade.”

Texts were produced by authors such as the famed Yamada family containing various gruesome diagrams. These form a fascinating — if queasy — catalog of everything the samurai got up to when testing a potential sword or swordsman. The Yamadas exemplified the art of the “otameshi-geisha,” the master cadaver splicers.

Particularly devastating cuts included “kesagiri.” This was where the sword sliced through the left shoulder, chest and right hip. Sometimes tallies of the dismembered were inscribed onto the blade, in a macabre guarantee of quality. These inscribed blades were more valuable.

Test subjects weren’t always dead, with live subjects sometimes brought in for tameshigiri. An extract from the 2011 book Samurai by John Man relays an anecdote from such a situation.

In a definitive example of gallows humor, the author refers to “a story of a criminal condemned to death with this cut (kesagiri) who joked with his executioner: ‘If I had known I would have swallowed a couple of big stones to spoil your sword!’”

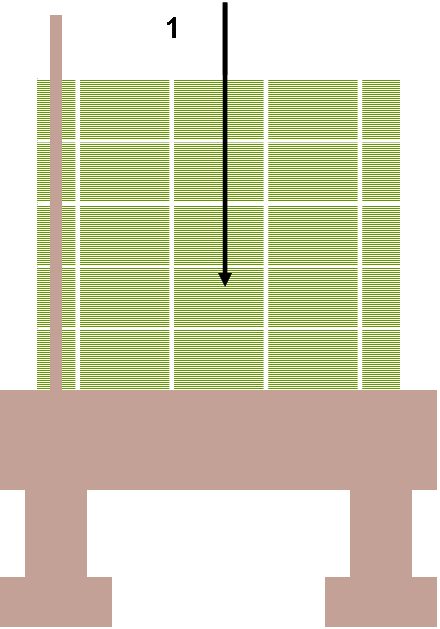

This poor individual may have been placed upon a “doden,” or “sand stand.” Sand or earth was shaped into a kind of tameshigiri cushion, and the body securely fastened to stakes. Why such a soft surface? It wasn’t for the target’s benefit.

As tameshigiri.ca puts it, “This form of stand reduced damage to the blade should the practitioner manage to cut all the way through, as the blade would enter the light sand without injury.”

The whole business of tameshigiri was developed and documented in meticulous detail, as you might expect from one of the most feared warrior classes on the planet.

Nowadays a new category can be added to the practice of tameshigiri: tourist attraction. In a 2017 article for the website Nine.com, an experience is offered at Chokeigi Temple, a site based in Sennan City, Osaka. The description sounds positively tame compared to the controlled barbarism of old. A modern day journalist is instructed by a sword master schooled in the traditions of his forefathers.

“A rolled-up tatami mat on a bamboo stand, known as a goza target, is placed a few paces in front of him. His sword sheathed, he moves toward the stand with the grace of a ballet dancer, releasing his sword and slicing the target with sharp precision. The severed piece of mat falls to the ground, a perfect 45-degree diagonal slice.”

Read another story from us: The Cyclops Myth – Two Competing Theories on How it Began

Notably this indicates the direction tameshigiri has gone, shifting focus from its practical use in conflict to a purely symbolic gesture honoring centuries of tradition. It still has the power to create shock and awe, though on a decidedly smaller scale. Though as history tells us, the background to this gold standard of sword tests is as eye-watering as the purpose the weapon was designed for.