Today, the worlds of industry and technology are plagued by worries of industrial espionage, data theft, and spying. Startups and even well-established companies are always on guard for fear that new ideas in development will be somehow stolen by competitors and used against them.

This isn’t a new concern; it’s one that has been going on much longer than most people think, according to PRI.

Back when the U.S. was only 13 colonies, it was still very rural and agricultural. In England, though, the industrial revolution was in full swing. As a result, the colonies were heavily reliant on English imports of both raw materials and made goods.

During the American Revolution there were major problems due to shortages of military supplies ranging from weapons and ships to shoes and uniforms.

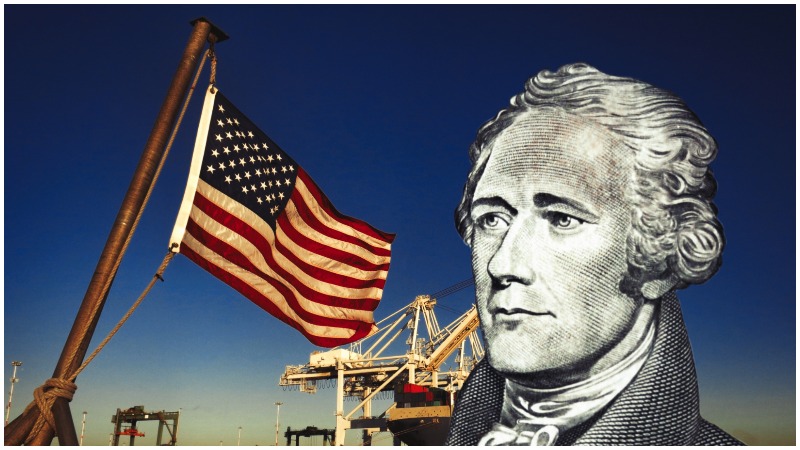

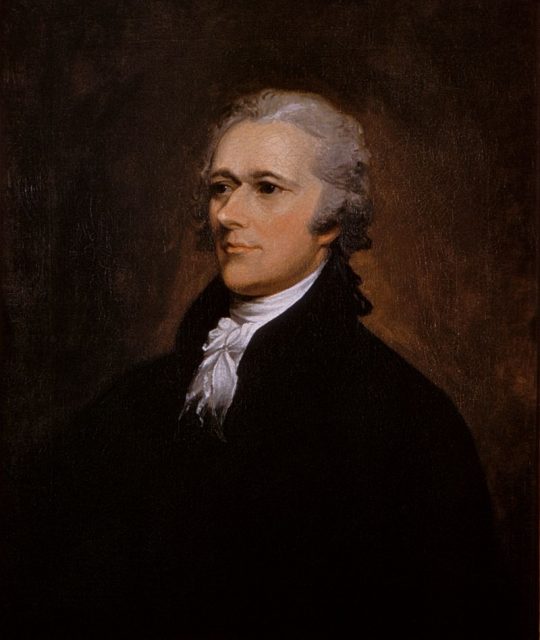

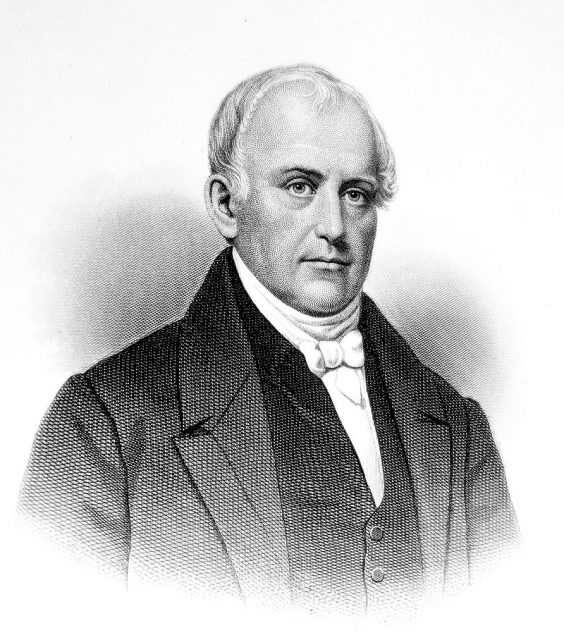

According to a 1791 Report on Manufactures that was presented to the newly formed American Congress, Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s first Secretary of the Treasury, and Tench Coxe, an economist and close associate to Hamilton, decided that the U.S. needed to industrialize, and the fastest way to do that was to lure industrial innovators and their ideas from England. America became a tech pirate.

Hamilton’s first victory along this path happened at the constitutional convention when he gained the power to issue patents from the federal government. The promise of patents could be used to lure innovative thinkers to come to America to pursue their work.

Building of the Norris Dam in Tennessee (1930s)

Hamilton and Coxe also created societies to encourage “manufactures and useful arts.” England was not in favor of these moves and had laws on the books making it illegal for anyone to take designs or machines out of the country or even lure away skilled workers. This prompted some of the nation’s earliest acts of industrial espionage.

One of the first spies was Andrew Mitchell. In 1787 he was caught, in England, trying to board a ship out of the country. When his trunk was loaded on board, it was seized and determined to be full of models and drawings for one of Britain’s great industrial machines. Mitchell himself was able to escape capture and flee to Denmark, but his stolen intellectual property was confiscated.

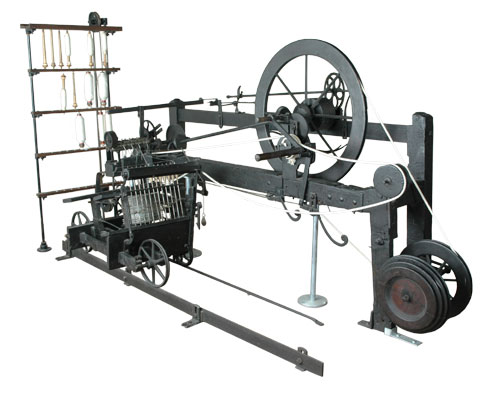

Another such spy was Samuel Slater. According to Popular Science, Slater was a child worker at an English textile factory that was using highly innovative industrial machines such as Richard Arkwright’s water-driven spinning wheel.

In 1789, U.S. factories were starting to pop up in the well-established cities on the east coast, but they weren’t yet very successful. Slater heard about the struggles, and, having worked for many years in the factory and being well versed in its processes, and more, having memorized perfectly and to the smallest detail the workings of the spinning wheel, he was able to leave England for America with the illegal plans in his head instead of on paper.

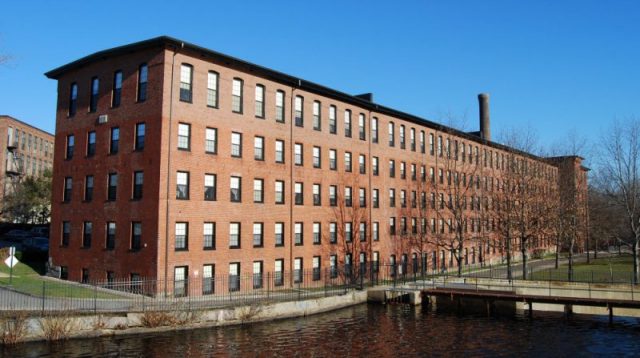

Two years later Slater wrote a letter to the Almy & Brown mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island promising to build them a spinning wheel which would make yarn of the same quality that could be had from England.

Slater’s designs enabled Almy & Brown to open a new mill three years later. Slater went on to split from his employers and start Samuel Slater and Company which grew to own multiple mills and factories. Slater became known as the “father of the American Industrial Revolution.”

In 1810, Francis Cabot Lowell visited England and spent his time charming his way into factories and trying to memorize how English designers had created automated machines for weaving. When he returned home to Massachusetts, he worked with a clockmaker to reproduce what he saw.

After a while, he and his associates built a whole new city around their textile factories on the Merrimack River, and the town was named Lowell.

Read another story from us: The Most Famous Duel in American History

The need to pillage foreign intellectual property died down early in the next century as American innovators began to come to the fore, but let’s not forget that, in the U.S., the push for industrialization was nursed along by spies.