For centuries, sailors had to cope with a major issue: the question of how to know where they were going once the land was out of sight. When traveling on terra firma, you could navigate by landmarks.

For close sea voyages, you could follow the coastline — but what if you wanted to go farther? How could you pick a path and know you were staying on it, regardless of wind or weather? When the ancients went looking for unfailing markers, the answers came in a few different forms.

According to PBS, the Norse watched the flight patterns of birds to determine their route. The Polynesians observed the birds, but also used the waves, watching for the faint gleam on the horizon indicating islands that were just out sight beyond the earth’s curve.

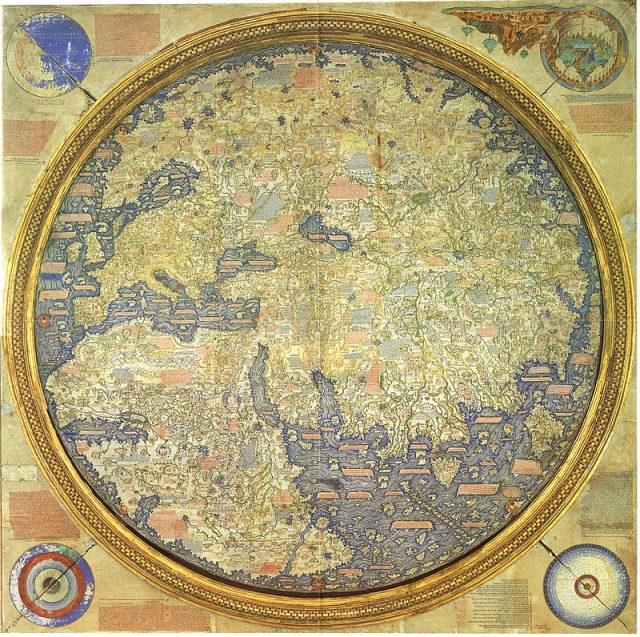

The Egyptians drew charts that marked longitude and latitude, although those became less reliable the farther one got from well-known waters. One of the best and most useful answers, however, was in the stars.

The ancient Phoenicians figured out how to navigate using the sun to give direction and quarter as it followed its path across the sky. At night, they steered by the stars. At any one time of the year, at any one point on the globe, the sun and stars are always at particular, fixed heights above the horizon.

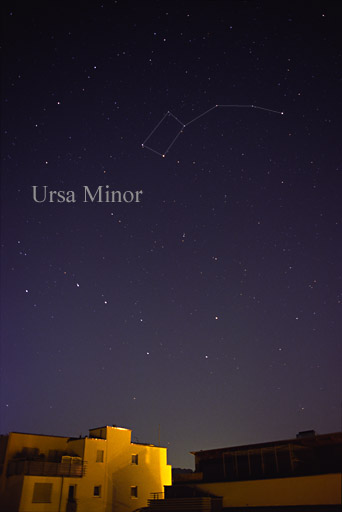

Ancient seafarers could measure that with as simple a tool as their fingers held horizontally and at arm’s length to fix a position or direction. The ancient Greek philosopher, Thales of Miletus, taught Ionian sailors to navigate using Ursa Minor a full 600 years before the birth of Christ.

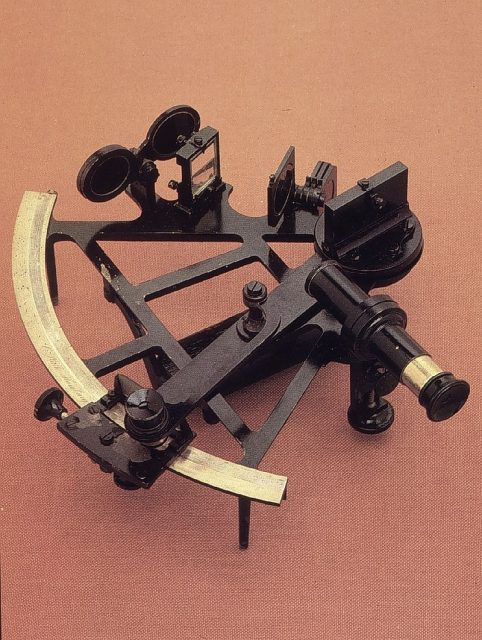

Over the centuries, more sophisticated devices were invented to measure the height of sun and stars over the horizon. By the Middle Ages, sailors used an astrolabe, which is a metal disc held suspended by a small ring.

The disc has a scale marked in degrees and a ruler for measuring heights. The best of these tools, however, was the sextant, which allowed those using it to find their latitude within a sea mile or two, even on a bobbing ship.

Who invented the sextant is a topic of some debate. According to Ocean Navigator, in the archives of the Royal Society of London, there are two affidavits by two different men, both sworn on March 27, 1733, essentially attributing the device to Thomas Godfrey, who made a design in 1730 for a double-reflecting sextant.

Godfrey gave the device and the idea to a friend, John Logan, so Logan could send it to the Royal Society of London, to notify them of the invention. Logan got caught up in other duties and didn’t mail the letter to the Society for 18 months.

The letter was “lost or misplaced” in London for two years and wasn’t read before the society until 1734. By that time, credit for the double reflecting sextant had already been given to one Thomas Hadley, who was a member of the Royal Society.

Reportedly, Hadley’s design was remarkably similar to Godfrey’s. John Campbell also designed a sextant, in 1757. His was remarkable for being the first such device that would allow the user to read longitude as well as latitude.

Celestial navigation is still in use in the modern day. The SR-71 “Blackbird” spy planes, which the Air Force used from the mid-‘60s until 1990, relied on it.

According to Smithsonian, the navigational system computes its position fix using stars sighted through lenses at the top of each unit. Those reference points offers course guidance with an accuracy of 300 feet!

The system was so sensitive it could detect stars in broad daylight while still on the ground. The military still looks at how they can best implement celestial navigation systems in future designs for fighting where there is no functioning GPS available.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FKZX5R_4bZQ

Even more recently, the Los Angeles Times reported in 2015 that the U.S. Naval Academy has reinstated teaching its students how to navigate by using the stars, after discontinuing the technique more than ten years ago.

It’s not because of maritime nostalgia either. Increasing fear of cyberattacks led to the decision. Lt. Cmdr. Ryan Rogers, deputy chairman of the academy’s department of seamanship and navigation said, “We went away from celestial navigation because computers are great. … The problem is there’s no backup.”

Clearly, the ancients were on to a good idea.