In 1778, Founding Father Benjamin Franklin was in France attempting to secure support for the United States Colonies during the War for Independence.

Great Britain and France had been at odds with one another for many years as the two most powerful nations in the world.

The American Continental Congress knew that enlisting aid from France would further infuriate King George III.

The Americans were fully aware they could not win the war with Great Britain alone. They had no navy, and military supplies such as guns and ammunition were hard to come by as the Colonies depended on Great Britain for most of their supplies.

The British had recruited North American Indian tribes to fight for their cause — promising if Britain retained control of the Colonies, the Native Americans would be left alone. The only hope the Colonists had was to enlist foreign aid.

The Colonies were forbidden to trade with foreign countries, but smuggling had been going on for years. American rice and tobacco were to be shipped only to Britain but were secretly shipped to northwestern France and Amsterdam in exchange for much-needed items such as tea, fabric for clothing, gunpowder, arms, wig powder and other necessities.

Great Britain was aware of the illegal trading but mostly ignored the situation until they found out about the weapons and gunpowder. In 1774, the British sent ships to Texel Island in northern Holland to curtail the trade with Amsterdam. According to Aermican Herritage by the beginning of 1775, the British had unknowingly sent almost six million dollars’ worth of war munitions to the Colonies.

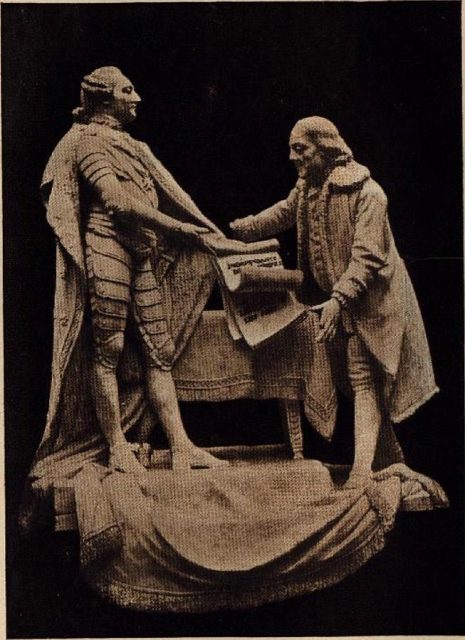

At the age of seventy-one Benjamin Franklin was sent to France, along with Silas Deane and Arthur Lee, to gain help from Louis XVI. On May 2, 1776, the French King signed documents making France an American ally which dishonored her treaties with Britain.

In 1770 Massachusetts appointed Franklin as the first foreign ambassador to France. By 1778, Franklin, Deane and Lee had negotiated the Treaty of Alliance and the Treaty of Amity and Commerce with their new ally.

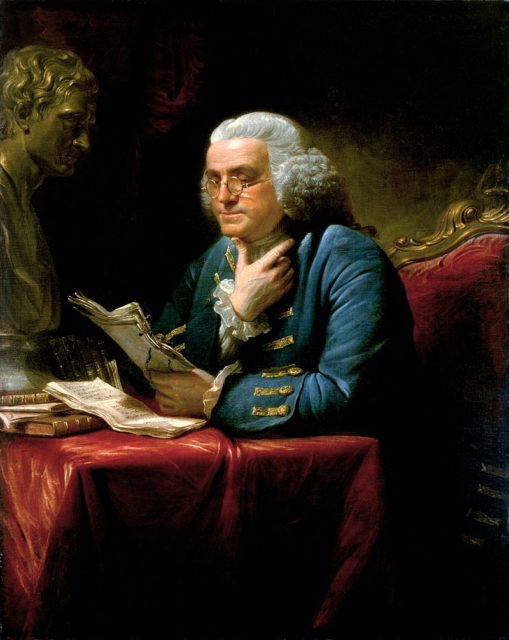

Franklin had already proved his worth in the Colonies by his writings, inventions, research of electricity, and his brilliant use of diplomacy. Although he was self-taught, Franklin held honorary degrees from Harvard, Yale, the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, and Oxford University in England.

He also helped found the University of Pennsylvania in his hometown of Philadelphia. The French, fascinated by Franklin, welcomed him with open arms. He learned French and was set up in a house in the Parisian suburb of Passy.

His charm, wit and humble dress made him one of the most popular people in Paris. He wore a coonskin cap to play up the French belief that Americans were wild frontiersmen. In fact, Franklin was so popular in France that even today some French citizens think he was an American president. Franklin was criticized by his contemporaries for living the high life, going to balls and parties and hobnobbing with the wealthiest of society.

For Franklin to have mixed with the poorer people would have alienated him from the king and wealthy potential donors to the cause. It was the eve of the French Revolution, and the public had had about enough of squalid living conditions while the wealthy flaunted their money in over the top decadence.

At the end of the Revolutionary War Franklin successfully negotiated the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

Having spent about ten years in France, Franklin returned to Philadelphia in 1785. He assisted in the creation of both the Bill of Rights and the United States Constitution.

In April of 1790, Franklin died at the age of eighty-four at the Philadelphia home of his daughter, Sarah. According to Biography, Franklin had written his own epitaph when he was twenty-two:

“The body of B. Franklin, Printer (Like the Cover of an Old Book Its Contents torn Out And Stript of its Lettering and Gilding) Lies Here, Food for Worms. But the Work shall not be Lost; For it will (as he Believ’d) Appear once More In a New and More Elegant Edition Revised and Corrected By the Author.”

Alas, the inscription on his headstone in Christ Church Burial Ground reads “Benjamin and Deborah Franklin 1790.” The Poor Richard Club mounted a plaque near the grave with Franklin’s epitaph for himself and another with a timeline of Franklin’s life.