In the long line of pharaohs of the dynasties of ancient Egypt, Akhenaten was unique. Yet until recently, almost nothing was known about him. Akhenaten lived during the 14th century BC and his reign lasted for 17 years.. Evidence of his existence was discovered only in the late 19th century.

The future king of Egypt was originally named Amenhotep IV, son of pharaoh Amenhotep III and Queen Tiye. He was not first in line to the throne but his older brother died at a young age. Some scholars believe that the young prince was shunned as a child, as he never appeared in family portraits. He later married the well-known Queen Nefertiti.

Once on the throne, Akhenaten made revolutionary changes to Egyptian life. He banished worship of Egypt’s many gods, including Amun-Ra, popular among the priestly class. Instead, only one deity, the sun disk god Aten, was to be recognized as the Supreme Being. Akhenaten considered himself a direct descendant of Aten.

Worship of Aten may have been the first known movement away from polytheism toward monotheism. Psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud once suggested that Moses may have been a priest to the cult of Aten, who later fled Egypt with his followers to maintain their beliefs after the death of Akhenaten.

After changing his name to Akhenaten, the pharaoh ordered grand monuments built for Aten in the Egyptian capital, Thebes. Temples were reoriented toward the east, where the sun rose each day. Icons for other Egyptian gods were removed.

Akhenaten then had a new city built in honor of his god. Two years later, he moved the royal palace there. The new city was located at modern day Amarna and was filled with up to 10,000 people. The population included priests to the sun god, merchants, builders, and traders. Akhenaten lived here for ten years until his death.

Along with statues, there were a number of sculptures portraying the royal family. This was common for the pharaohs of ancient Egypt. Almost all previous royal portraits depicted the king and queen as rigid. They are serious. They are wearing the royal insignia and their bodies are shaped perfectly and muscular. They look like gods themselves.

Not Akhenaten though. His face looks stretched. The nose is narrow and the chin is pointy. He has large lips and broad hips. A pot belly oozes over his waist. Why does Akhenaten look so different from other sculptures of the period?

One theory is that the king may have suffered some sort of ailment. One of the possibilities is that he had Marfan’s Syndrome, a genetic disorder that affects the body’s connective tissue. Some of the possible symptoms include a tall and thin body type, long arms, legs, and fingers, as well as curvature of the spine.

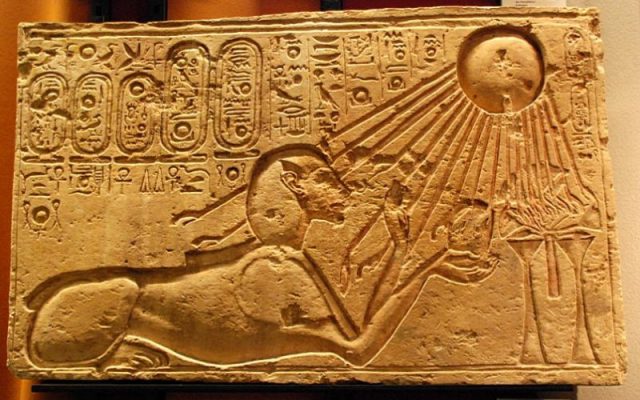

Yet, Akhenaten and his family look like real people with physical flaws. It is timeless. The images reach out to us through the many centuries. In one stone relief, the sun god Aten’s light is shining down on Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and some of their children.

The pharaoh is holding one child in his arms, giving her a kiss. Nefertiti is holding two younger kids, one child reaching for the queen’s jewelry. It’s a scene that might look like any contemporary family.

It appears Akhenaten’s rule was not popular, both within the kingdom and beyond. Correspondences from foreign rulers allied to Egypt describe frustration with Akhenaten’s lack of military and financial support. Egyptian power and influence declined during the king’s reign.

Akhenaten’s religious reforms did not outlive him. Almost immediately after his death, the priestly elites of Amun-Ra and the other gods regained their influence. Statues and references to Akhenaten and Aten were removed. Akhenaten’s name was erased from official royal lists.

His temples were destroyed and the material used for new building projects. The city at Amarna was abandoned — even the mummified body of Akhenaten was removed from his tomb, never to be seen again.

Akhenaten’s successor was one of his sons, King Tutankhamun, also known as King Tut. He is more famous today than his father because his tomb was discovered mostly intact by archaeologists in the early 20th century.

As his name suggests, Tutankhamun embraced the old deity of Amun-Ra and the traditional ways of ancient Egypt. During his short reign, King Tut mostly turned away from his father’s legacy, the heretic pharaoh, Akhenaten.