Uruk was an ancient city in Sumer and later Babylonia. At one time it was the most important city in ancient Mesopotamia. It was situated in the southern region of Sumer (modern day Warka, Iraq), to the northeast of the Euphrates river.

Thousands of clay tablets dug up in the ruins of what used to be the great city of Uruk show that it was indeed a religious and scientific center. It was here, according to Archaeology Magazine, that the the world’s oldest texts were written.

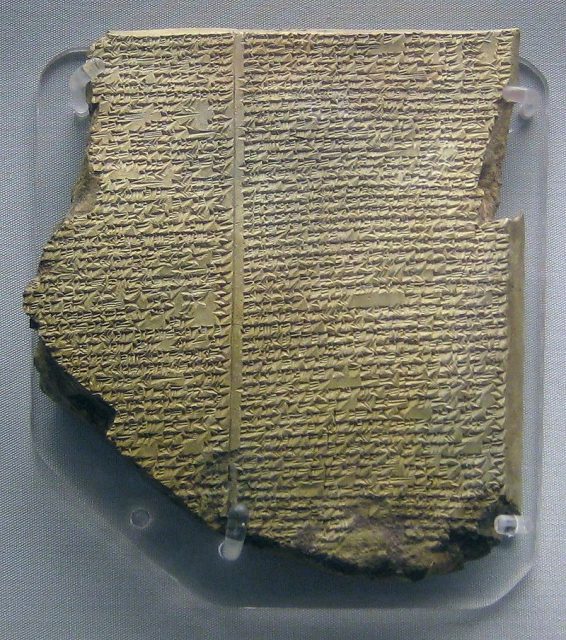

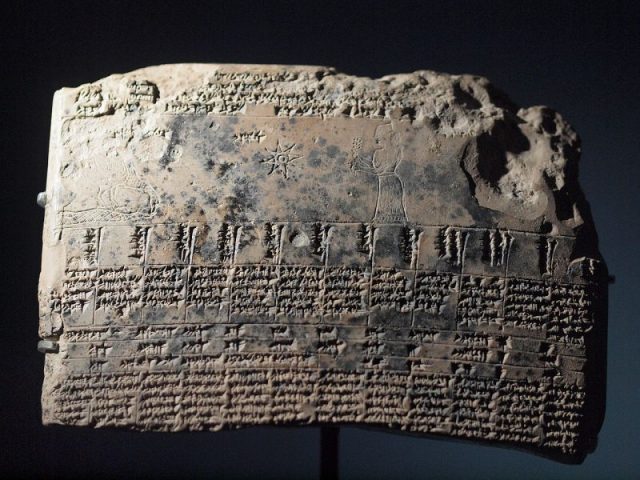

The writing system known as cuniform, a series of wedge-shaped symbols pressed into wet clay using reeds, was developed around 3200 B.C. by Sumerian scribes in Uruk. The combination of shapes represented different sounds, so the system could thus be adopted by scribes who spoke different languages. The script was used by multiple cultures for around 3,000 years.

Uruk is also well known as the city of Gilgamesh. The mythological Sumerian hero king was made famous in the modern world with the discovery of a collection of stories — known as the “Epic of Gilgamesh” — in 1853. The 12 cuneiform tablets on which the stories were written were discovered by archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam at the site of the the Royal Library of Ashurbanipal.

According to Professor John Maier of the State University of New York College at Brockport, “Ancient writings point to the existence of an actual, historical person we now call Gilgamesh. He lived, according to our best estimate, about 2600 B.C.”

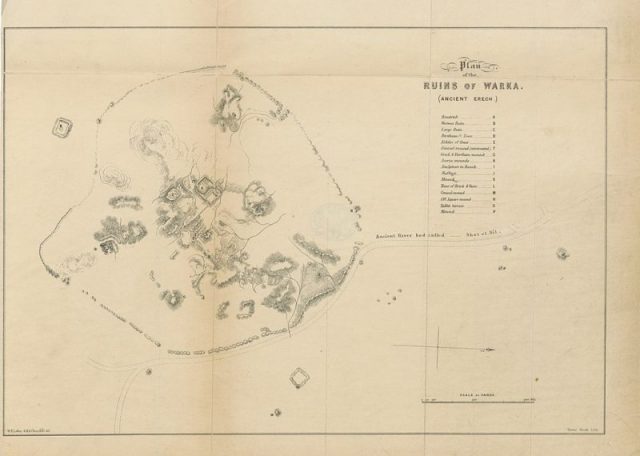

It is also believed that Uruk is the biblical city of Erech, the second city of the kingdom of Nimrod in Shinar (Genesis 10:10).

Archaeologists distinguish nine different periods in the rise of the city from a simple settlement to the first urban center of the world.

The foundations of the first settlements on the site date somewhere around 5000 B.C., the Eridu period. According to the Sumerian King List (an ancient stone tablet which lists all the kings of Sumer, in Sumerian language), Uruk was founded by King Enmerkar around 4500 B.C. This was during the Ubaid period (5000–4100 B.C.).

After 4000 B.C., Uruk rose from small, agricultural villages to a significantly larger and more complex center. This has been attributed partly to a period of climatic change; the area saw less rainfall and so people living in the hills migrated to the river valley of the ancient Euphrates.

The course of the Euphrates has since shifted, an important factor in the decline of the city.

Nestled in the lush and fertile river valley, the population of Uruk continued to grow throughout the Early Uruk period (4000–3500 B.C.), Middle Uruk period (3800–3400 B.C.) and Late Uruk period (3500–3100 B.C.). Farming and irrigation techniques were refined, providing a surplus of food for the community.

By around 3200 B.C., the city of Uruk was the largest settlement in southern Mesopotamia, and probably in the world.

It was an urban center with full-time bureaucracy, stratified society, and a formal military. It was also a major hub of trade and administration.

The organization of Uruk in this period set the blueprint for cities ever since. There is evidence of social hierarchies and coercive political structures that would be familiar to most of us today. Clay tablets containing a “standard professions list” have been found, listing around 100 professions.

As the city became more affluent, those at the top sought ways to display their wealth and power. Luxury goods were acquired by conquest or trade with lands as far as the Egyptian Nile Delta.

Uruk was a city of extraordinary architecture and works of art. The remains of monumental mud-brick buildings, the walls of which were decorated with mosaics of painted clay cones, pressed into the mud plaster — a technique known as clay cone mosaic — have been excavated.

The most impressive creations discovered to date of this Sumerian craft are the two large temple complexes in the heart of Uruk.

One was dedicated to Anu, the god of the sky, and the other, known as the Mosaic Temple of Uruk, to Inanna (or Ishtar), the goddess of love, procreation, and war. There was a clear division of the city into the Anu and Eanna Districts.

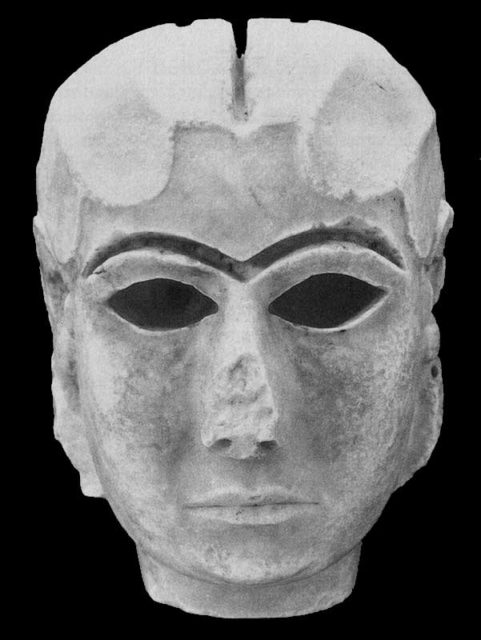

Another famous piece of artwork, “The Lady of Uruk,” or the Mask of Warka, was discovered in 1939 by the German Archaeological Institute in Uruk. Dating from 3100 B.C., it is most likely that the mask was part of a much larger work from one of the temples and it is considered to represent of Inanna. The marble sculpture is one of the earliest representations of the human face.

To this day, the mask is the most significant artifact found on the site, and it is part of the collection of National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad. It is also called “The Sumerian Mona Lisa.”

Uruk continued to expand and, as the center of luxurious materials and possessions, it demanded greater protection.

Although it was traditionally believed that the great wall of Uruk was built by King Gilgamesh himself, as it is written in the Epic of Gilgamesh, it was possibly created during the reign of King Eannutum who established the first empire in Uruk during the Jemdet Nasr Period (3100-2900 B.C.).

By the time the wall was raised, it protected an area of 2.32 square miles and a population of almost 80,000.

During the Early Dynastic period (2900–2350 B.C.), Mesopotamia was governed by city-states whose rulers gradually grew in importance and power.

Starting circa 2004 B.C. the struggles between the Sumerians in Babylonia and the Elamites from Elam, the Pre-Iranian civilization rose to serious national conflicts.

Uruk was still a prominent center during this time but suffered severely.

There are recollections about the conflicts in the Gilgamesh epic. Sometime after 2000 B.C., Uruk lost importance, but it wasn’t abandoned.

The city remained inhibited throughout the Seleucid (312–63 B.C.) and Parthian (227 B.C.–224 A.D.) periods. The last people living there left Uruk after the Islamic contest of Persia in 633–638 A.D.

The remains of probably the oldest city in the world laid buried until 1850 when archaeologist William Loftus led the first excavations on the site and identified the city as “Erech, the second city of Nimrod.”