The Siberian Times recently reported that a proposal is being announced for a project that would create a 4 million ruble paleo-scientific research center to be built in the Yakutia area of Siberia.

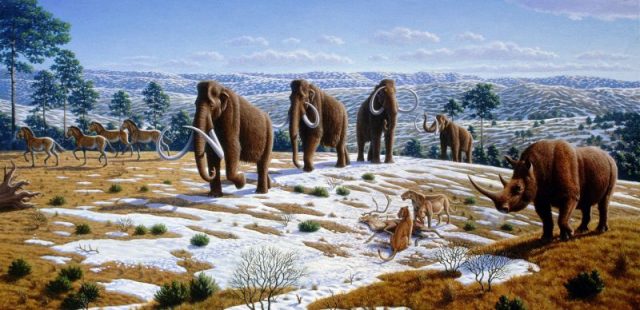

Its purpose will be to study genetic material from prehistoric animals such as the woolly mammoth and woolly rhinoceros, cave lions, and currently-extinct breeds of horses.

The ultimate goal would be to clone those animals. Plans have already been designed for laboratories sunk in the permafrost, to work with samples from several different species.

The proposal is being presented by North-Eastern Federal University in Yakutsk. NEFU is already closely involved in cloning research with the South Korean biotech foundation Sooam, with whom they would be partnering for the new research center.

The proposal is expected to be announced at the 4th Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok September 11-13th.

Yakutia is an excellent location for such a project, since approximately 80 percent of Pleistocene animals found with preserved soft tissue come from this region of Siberia. The preserved soft tissue is necessary for the extraction of usable DNA.

Russian scientists have been studying mammoth DNA for years, according to Russia Beyond, but it wasn’t until 2013 that Russian scientists were sent to South Korea to study cloning.

The mammoth’s genome has already been mapped, and it can be compared to that of the Asian Elephant. Changes can then be made to the elephant chromosome, creating a live mammoth chromosome.

The Russian-South Korean partnership is not the only group coming close to restoring the mammoth from extinction. The Guardian talked about a group of Harvard-based researchers in the U.S. who are moving in the same direction.

This group’s goal is to use the gene-editing technology CRISPR to modify an Asian elephant with mammoth DNA. This would make a sort of hybrid – an elephant with mammoth characteristics such as small ears, a woolly coat, and blood adapted to cold conditions. This team says they anticipate success within just a year or two.

The Guardian article brings up what should be another very important point in the discussion. Even if resurrecting the mammoth can be done… SHOULD it? For one thing, any attempt to clone a mammoth will probably require a live elephant to act as a surrogate.

Asian elephants are on the verge of extinction now and don’t do well in captivity. It would take not just one elephant; it would probably take a number of them to successfully breed a mammoth baby.

Does the potential benefit for humanity outweigh the potential suffering for the surrogates? Why choose a mammoth instead of some other animal that is better suited to a life in captivity or one which doesn’t require a surrogate mother, at all?

There have been some discussions of whether reintroducing mammoths to the steppe environment could help slow down climate change. Smithsonian reported that doing so could help prevent releasing more greenhouse gases from the melting permafrost in the tundra.

The permafrost in the Arctic tundra has been frozen since the Ice Age, and it holds huge amounts of carbon from dead plant life that’s contained in the ice. The volume of that carbon is estimated to be twice that of what’s in our atmosphere now. As the ice melts, it’s released as carbon dioxide and methane. This, in turn, speeds up global warming.

Mammoths and other large herbivores from the Pleistocene Era helped create a steppe landscape by trampling down shrubs and mosses and rooting up trees, leaving lots of grasses and herbs, but no trees.

The theory is that bringing these animals back would again spread the steppe environment more widely, cause the ground to absorb less heat, and delay the release of greenhouse gases — which would be great news for the world as a whole.

The drawback to this plan is that we really have no way to know what the impacts on the environment could be when we take such a step. We don’t know if the ecosystem’s changes were caused by losing animals like mammoths or if we lost the animals because of the changes to their ecosystem. It’s a gamble on what the end results would be.

Finally, it would take a lot of mammoths to really make a difference and a lot of time to breed them. Given the pace of climate change, it might take too long to make a real difference.

Read another story from us: Christian Charity Received Mammoth Bones in a Donation Box

Clearly, the idea of bringing back the mammoth is one that catches the imagination. The idea of having the ability to do so is pretty awe-inspiring as well. It’s an exciting idea to be able to look at something walking around that hasn’t done so in thousands of years. But it’s also a lot like playing God, and before taking such radical steps, we need to be very sure that we’ve given enough thought to the possible outcomes.