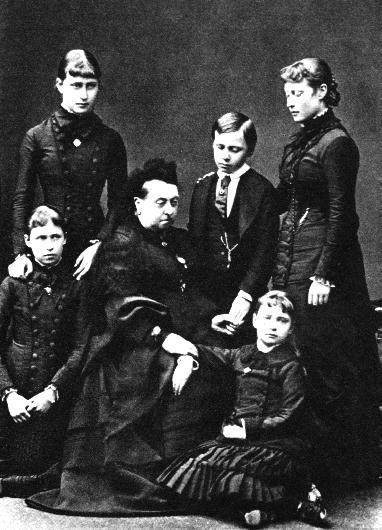

When Prince Albert succumbed to illness on a bleak December day in 1861, this marked the beginning of Queen Victoria’s period of mourning, which ended with her death some four decades later, in 1901.

The Queen never got over the loss of spouse of 21 years. Her prince’s death was premature, at the age of 42, so she stuck to dark outfits for the remainder of her years.

At the same time, this tragedy within the royal household was sort of booster to mourning dresses and etiquette — a lucrative business on its own right.

Crêpe, which was the most used fabric for sewing mourning attire, was used in such quantities that by the end of the 19th century, British fabric manufacturers Courtaulds had amassed a fortune by selling this type of textile alone.

As mourners needed to be supplied with proper clothing quickly, there were also numerous vendors who catered for their needs. In London, one of the most popular was Jay’s Mourning Warehouse, which opened in 1841.

Mourning etiquette was not so rigid in the early years of the Victorian era, but after Queen Victoria’s own Annus horribilis in 1861, things changed. Principles were indeed reinforced. What came out of the royal household was copied at every other layer of society, including the working classes.

The general rule was that a full mourning period over a loved one lasted a year, though the period was sometimes extended to two years, or as was the case with the Queen — it felt like it hardly ever ended.

The full mourning period was coupled with a half-mourning period which lasted for an additional two years. Victoria herself sported half-mourning dresses, overwhelmingly dark except little bits of white or purple, decades after Prince Albert’s demise.

It was toughest for widowed women, who were expected never to abandon their dark garments while grieving, as well as avoiding any social gatherings or events that had a hint of joy (as if this would aid the loss).

The widow’s outfit was known as the widow’s weeds. While it was all sewn in crêpe, the collars and the cuffs of shirts were edged with black piping too. Buttons were black and jewelry was also supposed to be dark, such as black pearls or jet-stones for those who could afford them. Those who couldn’t used cheaper imitations.

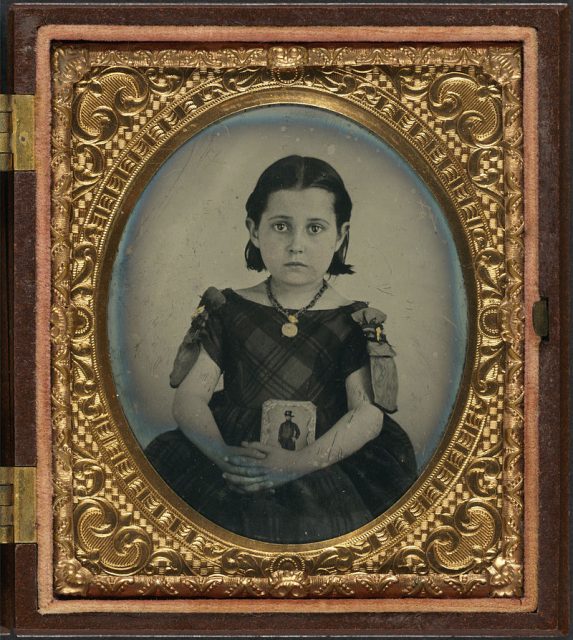

Another popular option was using a lock of hair belonging to the dearly departed. The relic was often woven in a beautiful knot and worn as a brooch, with it the memory of the lost one.

If a grieving person owned, for example, a pair of white gloves, these needed some adjustment. Embroidering with black thread would have done the trick.

A rare exception would have been the funeral of a young deceased girl, where white was among the acceptable colors in the outfit combinations, as it symbolized purity. However, this practice somehow disappeared.

To adjust to all such requirements of the abundant mourning etiquette required money and a manual. For the wealthier, a mourning period was more or less another chance to communicate their economic standing in society.

In case of multiple deaths in a household over a short period of time, it meant mourning phases extended for several years. All regular clothing during this period were stored away. By the time the mourning ritual was through, it was no surprise if those stored-away clothes had gone entirely out of fashion.

On the benefits of mourning warehouses, it was bad luck to keep attire at home after the mourning was through. The used black clothes were discarded. If someone else died afterward, the required outfit was bought anew — if you had the money to so often change your wardrobe.

Those who were unable to afford to purchase any black garments dyed and used what they already had.

Those not so familiar with the correct etiquette were able to check in any of the popular household manuals that were published at the time. Women, who stood out as leaders of the household’s mourning procedures, normally kept a copy of these manuals at home. Cassell’s and The Queen were among the most popular ones (so you could learn to mourn like a queen).

Such help books thoroughly instructed the reader on the most appropriate ways to mourn, among other tips on general dressing. There were tons of little rules that reflected on the sorrow and the sentiment of loss. And everyone was expected to abide by these when someone near and dear to them died.

The amount of black to be worn was dictated by the various stages of mourning, such as the full mourning year and the half-mourning stage that followed.

In specific cases, women were able to remarry past their sixth month of mourning, when there was a need: If the husband was abroad for years and missing, or perhaps suffered and passed due to a long, exhausting disease, and the woman had children to feed.

Other than this, it was acceptable for a woman to adopt a little grey or little purple on her outfit once she entered the half-mourning period. At this point, she was also able to go back to social gatherings.

The Workwoman’s Guide, published in 1840, details expected mourning time for loss of other relatives. A parent was to grieve up to half a year or a full year, and the same principle stuck for children older than ten. Below the age of ten, children were mourned up to six months. An infant was mourned six weeks at the least.

Siblings were mourned in between six and eight months, and uncles and aunties from three and six months. Friends were mourned three weeks at the least.

And men? It was a bit easier for them, at least with the outfit. A normal-looking dark suit combined with black gloves and dark-colored cravat would have been appropriate enough. A black ribbon was sometimes worn as an armband, too.

Children themselves attending a funeral were not expected to wear any mourning clothes, though they were sometimes dressed in white clothes.

Read another story from us: Dark Secrets and Scandals that have Rocked the Vatican

These rigid principles of deep mourning were somewhat abandoned once the Edwardian era commenced. Even more impactful was World War I. When the war was over in 1918, it seemed the entire world was mourning, and such rigidity didn’t really soothe anyone anymore.