Most people know the story of Sylvia Plath — the famed poet who took her own life at thirty years of age, distraught by the abandonment of her husband, poet laureate Ted Hughes. But few are as well-acquainted with Assia Wevill, the scorned “other woman” in this tragic love triangle — who, like the woman she supplanted, would die at her own hand.

Born in 1927, the daughter of a Jewish physician of Russian origin and a German Lutheran mother, Wevill spent her early years in Germany, until the persecution of Jews at the beginning of WWII forced her family to flee to Palestine.

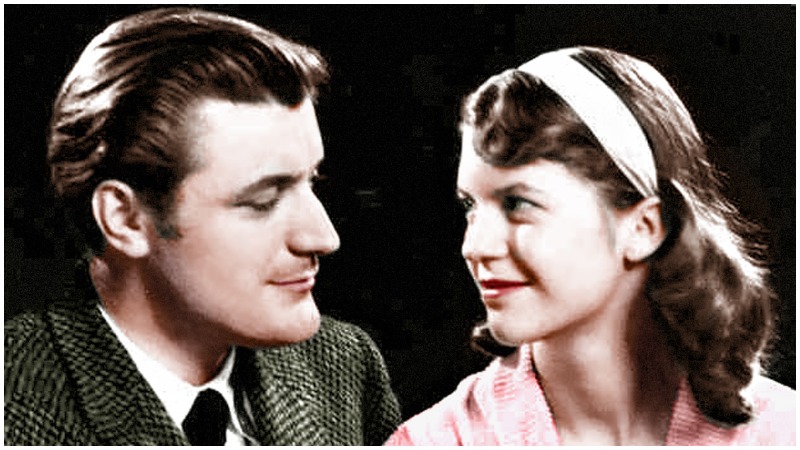

Years later, the striking and sophisticated Wevill was working as a copywriter at a London ad agency and happily married to her third husband, poet David Wevill. The couple, looking for a flat to settle down in, came upon the perfect place.

The owners: poets Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath, who were renting it out while they moved to the Devon countryside, in an attempt to get their marriage back on track, far from the turbulence of the big city.

Their new home, Court Green, was certainly bucolic, but life so far from the city can be lonely. In the winter of 1962, Plath and Hughes invited several couples to Devon to stay for the weekend — among them, David and Assia Wevill.

It would be a turning point in both relationships. Plath, well-attuned to her husband’s wandering eye, couldn’t help but notice the chemistry between Hughes and Wevill. Her radar was dead-on.

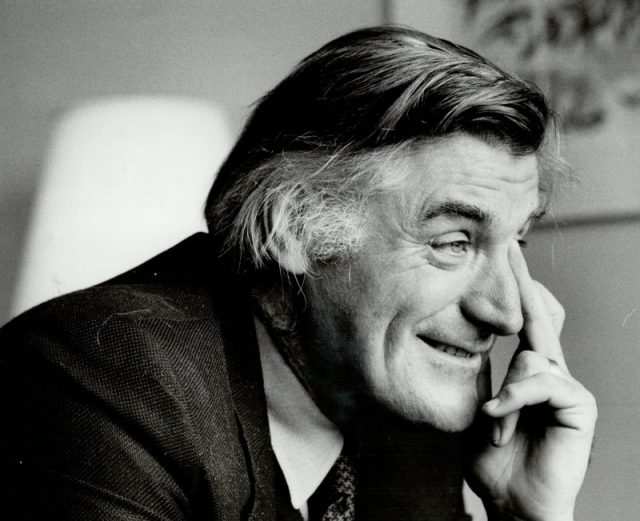

Weeks later, Hughes went to the ad agency where Wevill worked, leaving a note: “I have come to see you, despite all marriages.” Message sent. Soon the two were meeting in hotels or the back of a borrowed van.

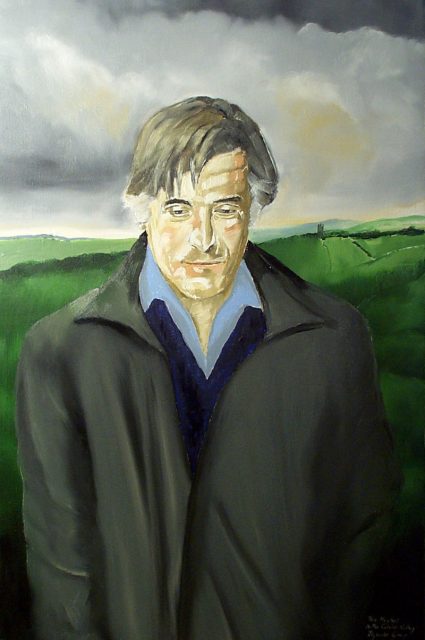

Upon learning of the affair, David Wevill swallowed a handful of sleeping pills. Plath’s reaction was one of rage. (At one point, she built a bonfire in the yard, tossing her husband’s letters and manuscripts into the flames.) Plath would soon realize the mistake of her actions: Hughes fled to London, staying with a friend. The affair continued, but Hughes refused to make a choice, returning to Devon each week to spend time with his wife and children, Frieda and Nicholas. Wevill was equally torn between the two men in her life.

Back in Devon, Plath and Hughes continued to fight bitterly. In December, Plath had had enough. It was her turn to move to London, finding a flat for her and the children. By February, she decided to give the marriage another chance, but it was too late. Hughes and Wevill’s affair was no longer cloaked in secrecy — and Wevill was carrying Hughes’s child, though she would have an abortion soon after Plath’s death. Hughes wanted no more children and Wevill wasn’t keen on becoming a mother.

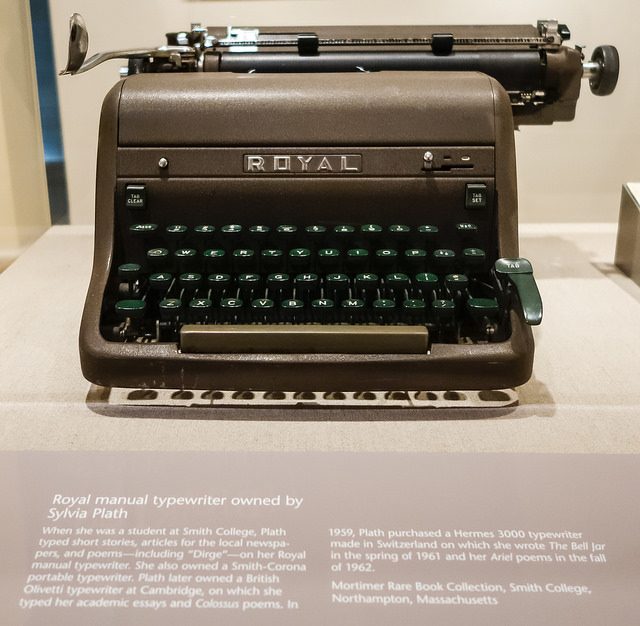

On February 11, 1963, Plath took her own life, gassing herself in her kitchen while her children slept on the floor above. Close friends, who had no idea of her husband’s whereabouts, tracked down his mistress, who ended up breaking the horrific news to Hughes. He immediately moved into the flat to tend to his children, while Wevill shuttled between the London flat and her home with David. Though Plath suffered from clinical depression, her friends blamed her rival for her death. But if Wevill shouldered any of the responsibility, she didn’t show it.

That May, back in Sylvia’s flat — this time for good after a separation from her husband — Wevill turned 36. Life ran smoothly, for a while anyway. Wevill discovered, to her great surprise, that she enjoyed being a stepmother.

“Fantastic, the way children (not even my own) have finally surrounded me,” she wrote in her diary. “The children I like, very much. I shall like them ever better, I think, when they are a little older.”

Ted, editing Plath’s poems into a book, rarely mentioned his wife’s name, but Wevill knew better. “Sylvia [is] growing in him, enormous, magnificent,” she wrote. “I am shrinking daily, both nibble at me. They eat me.”

In March of 1965 at age 37, Wevill gave birth to Alexandra Tatiana Elise, nicknamed “Shura.” Two years later, they would come to live at Court Green. By then, the dynamics of her relationship with Hughes had changed.

He suffered from dark moods and the couple fought frequently. Wevill was learning how hard it is to compete with a memory. Hughes, perhaps not understanding what she was going through, would unknowingly torture her with stories of “dream-meetings” he had with Plath as he slept.

Adding to Wevill’s internal turmoil: suspicions about her lover’s faithfulness. The fact that Hughes was reluctant to settle down with Wevill and their daughter didn’t help. Heartbreakingly, he refused to claim Shura as his daughter (at least publicly).

Shunned by her lover’s friends and family, not to mention becoming a pariah in the eyes of Plath’s many fans, Wevill would become but a shadow of the seductress who first enticed Ted Hughes.

What’s more, mirroring the woman that she supplanted, Wevill had to endure Hughes’s wandering eye. Among his infidelities: Carol Orchard, a woman twenty years his junior, who Hughes would marry in 1970.

Visibly older and pounds heavier, Wevill would return to London. In March of 1969, she dragged a mattress into the kitchen of her London flat, dissolved a handful of sleeping pills in a glass of water, and shared the potion with her four-year-old daughter.

Then she turned on the gas stove and crawled into bed with the child.

In her will, Wevill expressed the wish to “be buried in any rural cemetery in England, the vicar of its parish not objecting to its burial.”

Instead, Hughes would have her remains cremated. The epitaph, chosen by Wevill, would read: “Here lies a lover of unreason and an exile.”