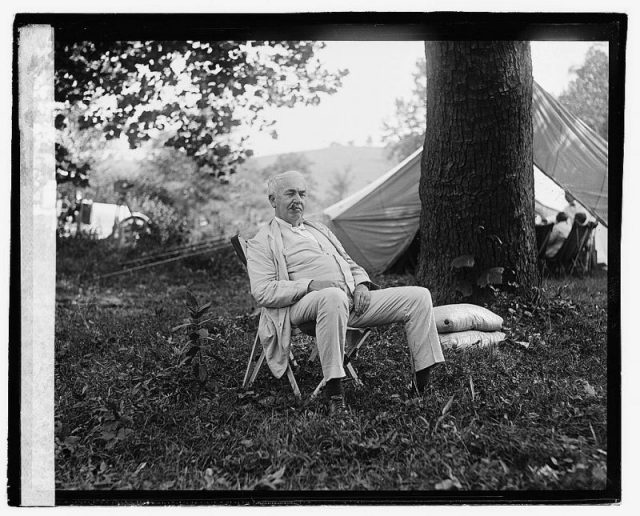

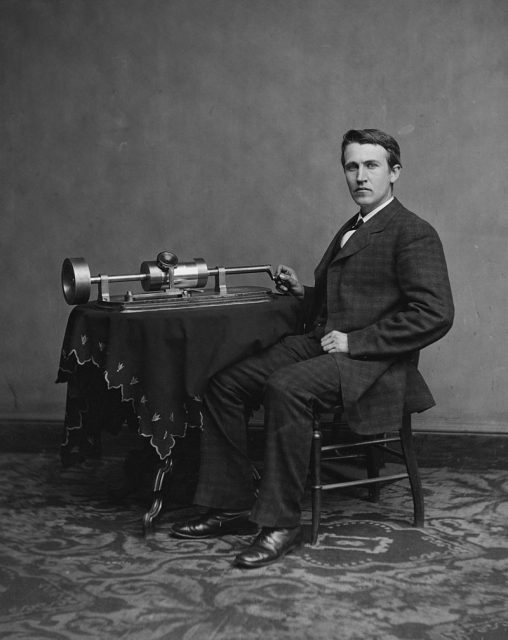

During his 69-year career as an inventor, Thomas Edison acquired a jaw-dropping number of patents (1,093 to be exact). Among them: the incandescent light bulb, the phonograph, and the movie camera. But make no mistake: There were some stinkers too.

You might say that the Wizard of Menlo Park met his Waterloo in 1890, with the invention of a 22-inch cherub, known today as the Edison Talking Doll.

Edison figured the toy would be a great way to demonstrate the at-home entertainment possibilities of his then-spanking-new wax cylinder phonograph.

Instead, all he succeeded in doing was creeping people out.

The press, at first, was intrigued. One 1888 newspaper headline read “The Wonderful Toys Which Mr. Edison Is Making For Nice Little Girls.”

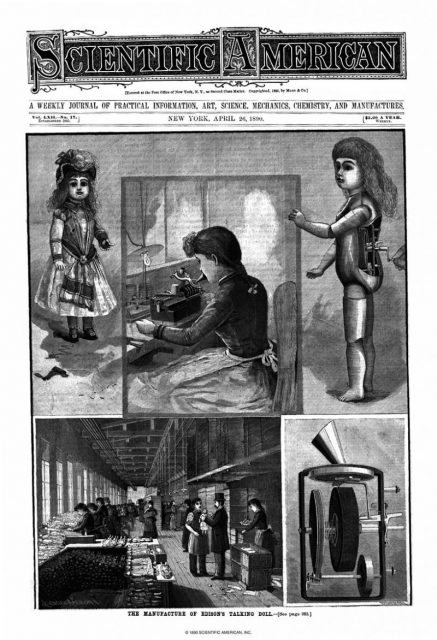

Then people started noticing the creepy factor. The doll, standing 22 inches and weighing a cumbersome four pounds, had wooden limbs, a porcelain head, and a decidedly unsettling, glassy-eyed stare.

As if the doll’s eerie appearance wasn’t off-putting enough, there was the voice. Inside the metal torso was a miniature phonograph whose recording surface was etched with 20-minute renditions of one of a dozen familiar ditties, such as “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” “Jack and Jill,” “Hickory Dickory Dock,” “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” and “Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep.”

By turning a hand crank sticking out of the doll’s back, one could play a rhyme.

But instead of the charming, sing-songy voice of a child, the sound that emanated from the doll was more like a terrified female being forced to read ransom demands under the threat of bodily harm. (audio below)

Indeed, the recordings were made by young women, who sat in factory cubicles and shouted the words into recording machines.

Suddenly the newspapers, which formerly touted the toy, turned sour, mocking Mr. Edison and his creation.

A Washington Post headline which read “Dolls That Talk: They Would Be More Entertaining if You Could Understand What They Say,” was surely one of the kinder comments.

Also dooming the doll: its hefty price tag—$10 for an undressed doll to $20 for a clothed one. (That would be the equivalent of around $237 and $574 today.)

The public weighed in with a collective “meh”. Edison would sell fewer than 500 dolls, and just a few weeks after the ballyhooed unveiling, he had them removed from store shelves.

Undeterred, the inventor set out to produce a new and improved version of the doll.

But in the fall of 1890, the Edison Phonograph Toy Manufacturing Company, deeply in debt and unable to land a loan, was humanely put out of its misery. Edison was probably relieved. After the business went belly-up, he would refer to his creations as ‘little monsters.’”

Today, only a small number of the dolls still exist; most are part of private collections. But thanks to new technology, you can actually hear their original voice. Prepare to be freaked!

Barbara Stepko is a New Jersey-based freelance editor and writer who has contributed to AARP magazine and the Wall Street Journal.