The United States fought a series of three wars against the Seminole people of Florida, beginning in 1816 and ending in 1858. These wars cost the lives of some 1,500 Americans and cost millions of dollars.

Though other conflicts in the West captured the imagination of historians, novelists and film-makers since the opening of the frontier, to this day the three Seminole Wars are the costliest the United States fought against Native tribes. And they never officially ended.

When the wars (which began in 1816) ended in the late 1850s, no treaty was ever signed ending the conflict between the United States government and the various groups of Seminoles in Florida.

What ended the war was an offer of money to the leaders of the Third Seminole War to move west to reservations set aside in Oklahoma – after American troops had captured relatives of the main Seminole chief Holata Micco, known in English as “Billy Bolek” or more usually as “Billy Bowlegs” (which he did not have). Small groups of Seminoles remained in Florida, and those and their tribe-mates who returned to the state formed the basis of the Seminole in Florida today.

The Seminole Tribe is not truly indigenous to Florida, though Florida today is recognized as their homeland. The Seminole are a successful example of people from many nations coming together to form a new one.

The groups were originally formed by tribes that came southward, trying to avoid the expansion of white colonists in the Carolinas. The two original groups of people, the Yamasee and the Yuchi tribes, migrated to Florida in the early 1700s and were later joined by people from the Lower Creek tribe in the late 1700s.

The Lower Creek held land in southern Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama and western Florida, but were in conflict with both white colonists and other tribes. Later migrations included groups of Choctaw and Chickasaw, both fleeing Georgia due to white expansion and tensions/conflict with tribes allied with the whites. Eventually included in some Seminole groups were bands of escaped slaves. These were known as the “Black Seminole.”

Throughout the 1700s these groups (which may have included handfuls of whites escaping harsh conditions in the penal colonies of Georgia) formed a new group of people that called themselves “Seminole,” which is a Creek word which can be translated as meaning “wild men” or “runaway men.”

By the time the First Seminole War began in 1817, a larger number of Creeks, calling themselves “Red Sticks” after the color of their war clubs, joined the Seminole bands in Florida. The Seminole are estimated to number about 6,000 people at this time.

The groups were scattered about northern and north-western Florida at this time. Florida in 1817 was a Spanish possession, but at the time the Spanish Empire was in decline and among their possessions in the New World, Florida was the least profitable, and of least interest.

They also paid various tribes to raid American border settlements in Georgia to keep the Americans at bay. Conversely, the Americans frequently made incursions into Florida, attacking Spanish garrisons at times, but mainly raiding Indian settlements in the search for escaped slaves. Some of the fighting resulted in the deaths of women and children of both sides.

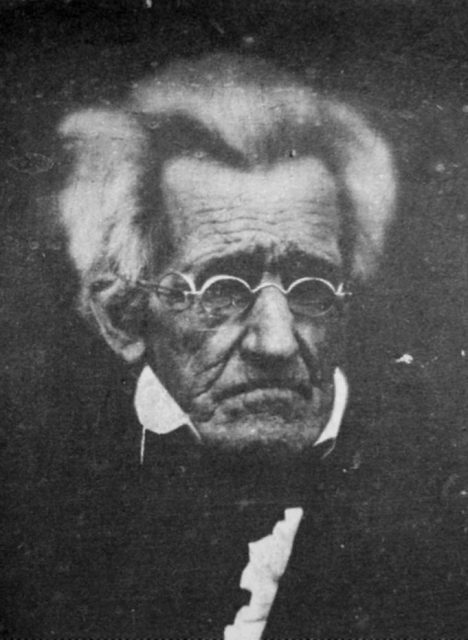

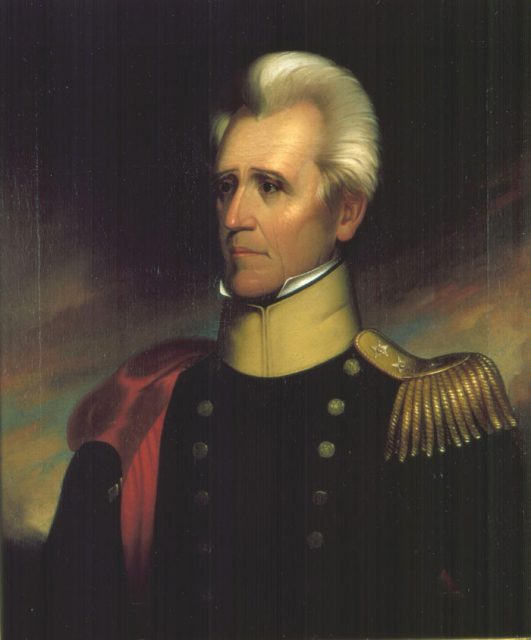

These incidents led to the First Seminole War. The U.S. forces were led by future President Andrew Jackson, who lately had achieved fame in the War of 1812. The First Seminole War also involved British and Spanish nationals and their treatment by Jackson — two British citizens were executed by order of Jackson for acting against the U.S. government.

Spain supported the Seminoles against the Americans and U.S. forces employed large numbers of Creek natives in their war in Florida. In many ways, this was to be the model of later Indian Wars on the western frontier – divide and conquer.

The First Seminole War ended in 1819 with the Spanish ceding Florida to the United States, and the Seminoles agreeing to move to a large reservation in the center of Florida, though some Seminole chiefs did keep lands in north Florida.

The second and most bloody of the Seminole Wars began after a short period of peace, which saw the Seminoles living on the assigned land, but occasionally wandering off it to hunt.

Increasing white settlement and larger numbers of escaped slaves allying themselves loosely with the Seminoles were the reason for growing calls by whites to have the Seminoles removed to the Creek reservation in Oklahoma – though the Seminoles had deliberately removed themselves from the main group of Creeks in the last century.

Disorganized at first, a group of chiefs went to the Creek reservation and met with U.S. representatives. The U.S. government made a show of it, stating that the Seminoles had agreed to leave Florida. When they returned to Florida, the Seminole chiefs loudly declared their opposition to being moved.

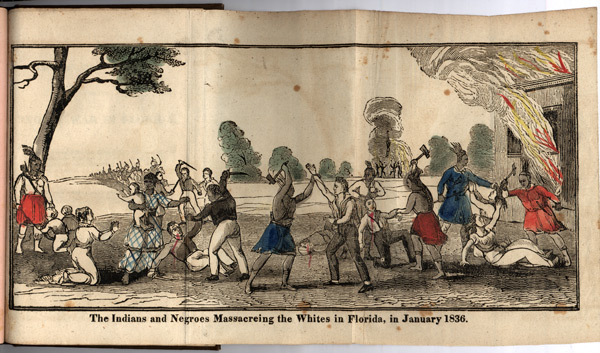

As this was happening, and for a short time afterward, a series of extremely violent events occurred between white settlers, troops and the Seminoles – some of which were marked with mutilation, rape, etc, by all sides.

Though some American officers, such as Major Ethan Allen Hitchcock saw the Seminoles’ reaction as being the result of Americans going back on their word, most Americans were inflamed with hatred for the Seminoles, and the Second Seminole War broke out in late 1835.

The war did not initially go well for the U.S. forces. At the time, the U.S. Army as a whole numbered less than 10,000. Volunteers were called for, and those that did were woefully unprepared for combat, the climate, and the nature of Indian warfare.

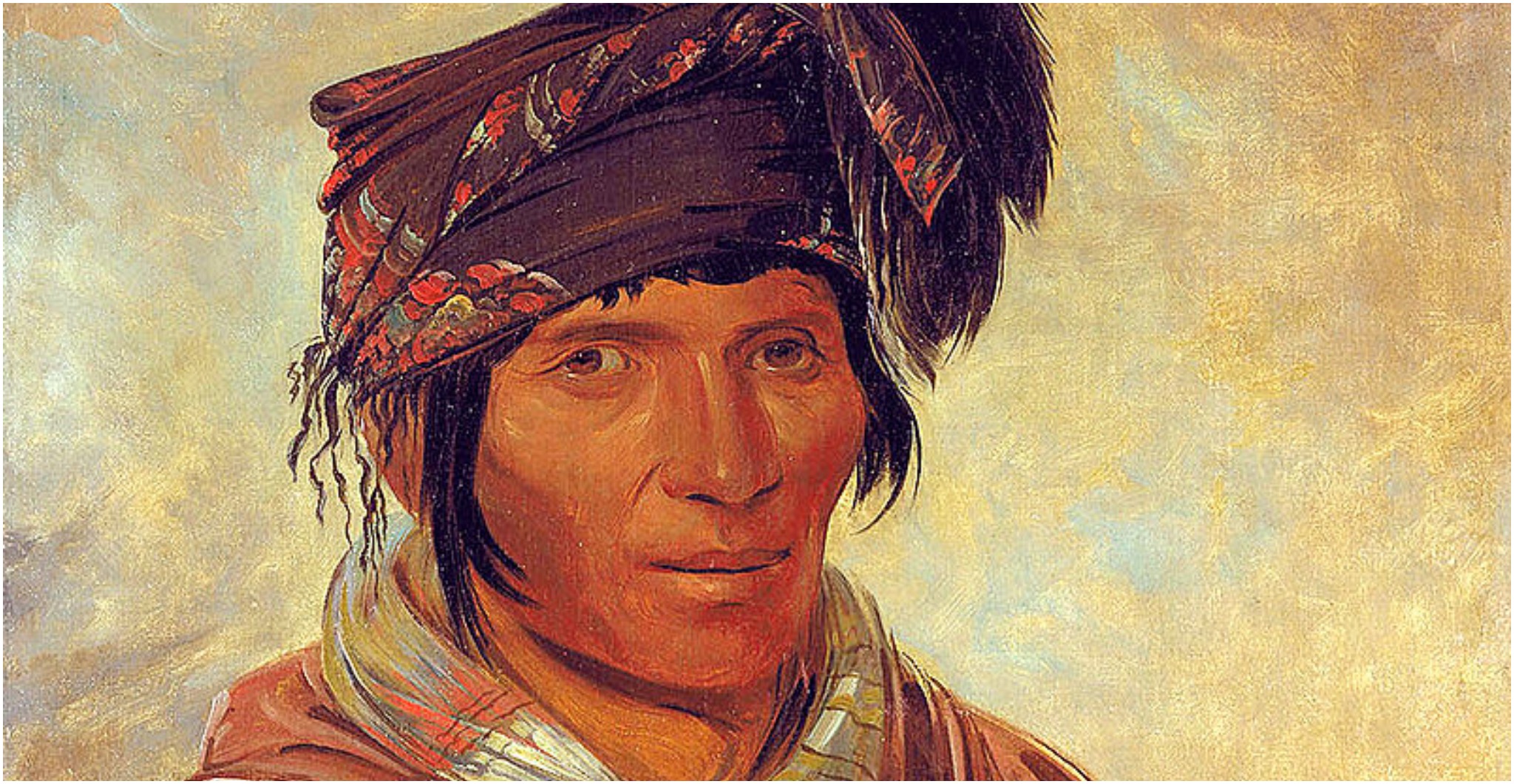

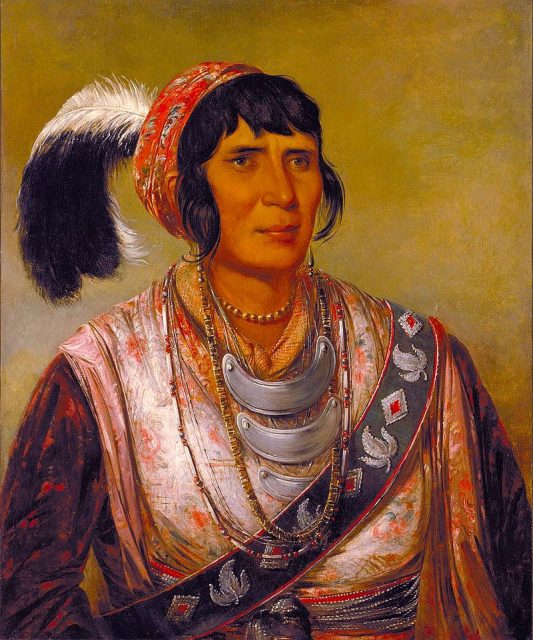

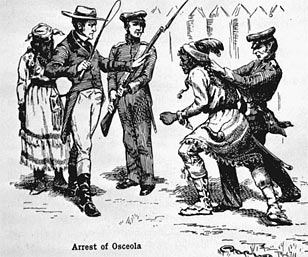

For about a year, the Seminoles inflicted a series of defeats on the Americans, who called forth more and more troops to force the Seminoles into a treaty or destruction. The most famous leader of the Seminoles was Osceola, a firebrand, but many other chiefs were involved in the war.

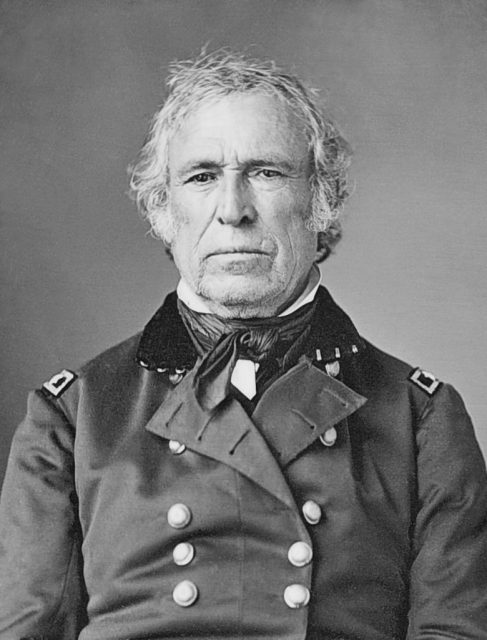

Eventually, U.S. troops led by future President Zachary Taylor did subdue the Seminoles, but it took more than just armed force. A combination of bribes to move, hunger and war reduced the Seminoles in Florida to about 300 by 1842.

By this time too, the American public and government was tired of the war, which threatened to continue as a violent guerrilla type conflict for years. Perhaps 1,000 U.S. troops and twice that number of Seminoles had died, along with hundreds of non-combatants.

Eventually, the Second Seminole War just petered out – Congress would authorize no more funds for it, the Seminoles in Florida had been reduced in number, and the public was tired of war.

The Seminoles were limited to the reservation area in central Florida and a “buffer zone” was placed around it which theoretically forbade both whites and Natives from entering. However, some whites entered to settle and Seminole hunting parties often left the barren reservation for food.

Another problem was miscommunication. A trading goods store on the west coast was destroyed after Seminoles believed white rumors about the proprietor being an agent of the government, plotting to remove the Indians from Florida.

Between 1848 and 1855, small bands of Seminoles throughout the state fought with militia, troops and raided settlements. Though nowhere near the size of the tribe of the Second Seminole War, their small size allowed the Seminole bands to more successfully evade the U.S. Army.

However, a tireless pursuit kept the Indians hungry and on the run. By 1858, the main Seminole chief, “Billy Bowlegs,” a veteran of the Second Seminole War, finally agreed to a cash payment and land in Oklahoma. He and about 200 Seminoles headed west, though the chief died shortly thereafter.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=auNOGcmYYSI

One or two other groups did the same, but various small bands remained in Florida. The government, believing that the main resistance had been quelled, left them alone in the swamps. No treaty ending the war was ever signed.

The Seminoles faced discrimination after the Civil War, and it was not until the Civil Rights Act of 1965 that they gained the right to vote. Slowly building small businesses based on tourism and small and then larger scale gambling, the Seminoles of Florida gradually became an economic force. Today, they own, of all things, the “Hard Rock Cafe” chain.

Other recognized groups of Seminoles live in Oklahoma, and the Miccosukee band of Seminoles, a more traditional group, live in central Florida, making their living through Eco-tourism.