About five miles north of the Great Pyramids at Giza sits the hill of Abu Rawash. On top of the hill sit the ruins of the Pyramid of Djedefre. Djedefre was the son of the pharaoh Khufu, who built the Great Pyramid.

Khufu’s pyramid rises to nearly 483 feet, which made it the tallest human-built structure in the world until the building of Lincoln Cathedral in the 14th century, according to the Archaeology News Network.

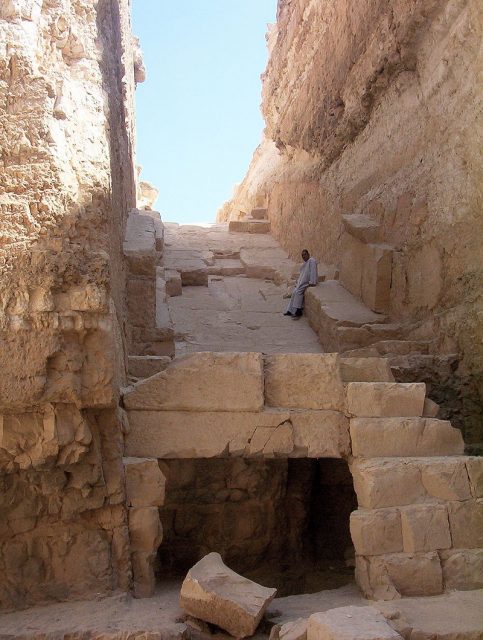

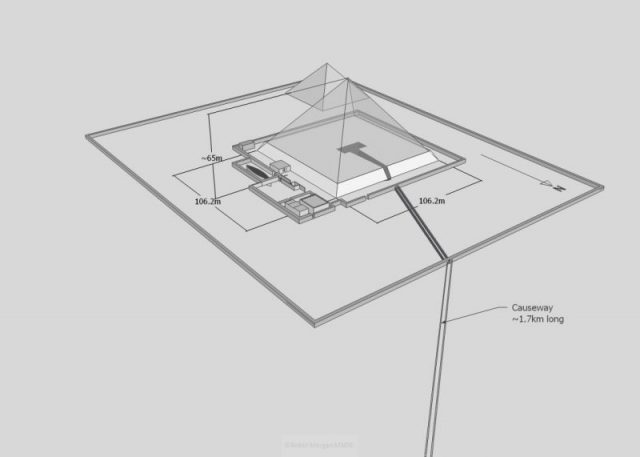

Djedefre’s pyramid is of a somewhat smaller scale, about the same size as the Pyramid of Menkaure, which is the third largest of the pyramids at Giza. He was ambitious, though. If Djedefre’s pyramid stood complete, the hill it sits on would put the pyramid’s tip at about the same level as Khufu’s. It’s not complete, though. All that remains of Djedefre’s construction today are the pyramid’s lower tiers, which extend about 30 feet high.

The site at Abu Rawash has been explored many times since the early-mid 19th century, but there is much about it that remains a mystery. The first, and most obvious, question is how this pyramid came to be in in its current state.

There seems to be some disagreement about whether it was ever even finished. Ancient Egypt Online, for example, states that the pyramid had once been complete and attributes its current state to having been used as a quarry and military base during the Roman era.

Dr. Michael Baud of the Louvre, one of the archaeologists who have worked to excavate the site, disagrees, although he did say that the sheer amount of granite still piled about suggests that the pyramid was at least half built, and maybe more, and that is after hundreds of years of stone being carried away from the site for use in other projects.

There are also disagreements about whether or not Djedefre’s pyramid was a pyramid at all or whether it was a solar temple instead. In 2008, Newsweek ran a fairly scathing piece in response to “The Lost Pyramid,” a documentary the History Channel was airing on the pyramid at Abu Rawash.

One issue that the piece brought up was that Djedefre’s construction had walls with a 60-degree slope, instead of the 52-degree slope of the other pyramids, meaning that it would actually be considered a sun temple.

Vassil Dobrev, of Cairo’s French Institute of Archaeology was cited in the article as saying, “It has never been lost, and it’s not even a pyramid.” Michael Baud disagrees, although he does say that there is a strong solar connection. Baud said that they have found an enormous number of statue fragments made out of quartzite and that ancient Egyptians associated quartzite with the sun.

When Dr. Baud was asked about Dobrev’s claims, he replied that solar temples “are known monuments…there is nothing like it at Abu Rawash.” He went on to say that it was a funerary complex with a solar connection, but couldn’t accept that it was just a solar temple. The solar connection is entirely logical, considering that Djedefre was the first pharaoh to add “son of Ra” to his birth name, according to Ancient Egypt Online. Ra was the Egyptian deity of the sun.

Another of the disputes about the pyramid revolves around its location. Djedefre chose to build his pyramid five miles from Giza where the pyramids of his father and brothers lay. Some archaeologists believe this may have been due to some sort of familial dispute, according to the Archaeology Department at Michigan State University, although there is no decisive proof this is true.

Michael Baud says that Djedefre’s decision to build his pyramid at a distance from his father’s was not unusual at all, but rather his brother, Khafre, was unusual in deciding to build his pyramid so close to his father’s at Giza.

All of this demonstrates how much of our attempts to fill in our history are basically guesswork. All archaeologists can do it look at the pieces of the puzzle and do their best to interpret what they see, but even among well-known experts, what they conclude isn’t always the same.