Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) works and person are enigmatic. Historians and music critics, both during his lifetime and today, are divided about his works and the essence of the man. Some say his works are extremely hard to fathom and equally hard to listen to.

Nonetheless there is no denying the impact his 7th symphony had on the outcome of the city Leningrad (now St. Petersburg, Russia) and on the fate of World War 2 as a whole. Written and performed while the city was under one of the most harrowing sieges in history, it came to embody strength and defiance in the face of overwhelming adversity.

To this day, over seventy years after it was written, the “Leningrad Symphony” is considered the musical symbol of the Soviet Union’s/Russia’s resistance and triumph against Hitler in WWII.

It is played every year at a memorial for the heroes of the city of Leningrad who number a half million (and likely many more). The first strains of the work are still likely to induce tears in Russians young and old, much like the strains of Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture did when Napoleon’s invasion was remembered.

Shostakovich himself is the subject of debate. Some consider him a middling talent. Others a great one. Still others believe that his talent was purposely suppressed in a time when everything, including musical works (even those without lyrics) was political.

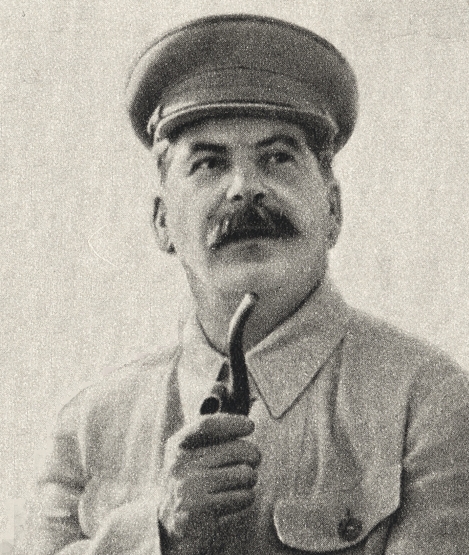

Other voices say he was a political survivor who simply did what he could to get by. The truth is likely somewhat a combination of all of these things. No one who lived during Stalin’s reign of terror could truly be his or herself. One always was guarded, and trusted very few, if any. Shostakovich himself was many times on the verge of arrest or worse – not for his words, but solely because of his art, and the qualities that Stalin and his many toadies attributed to it or not.

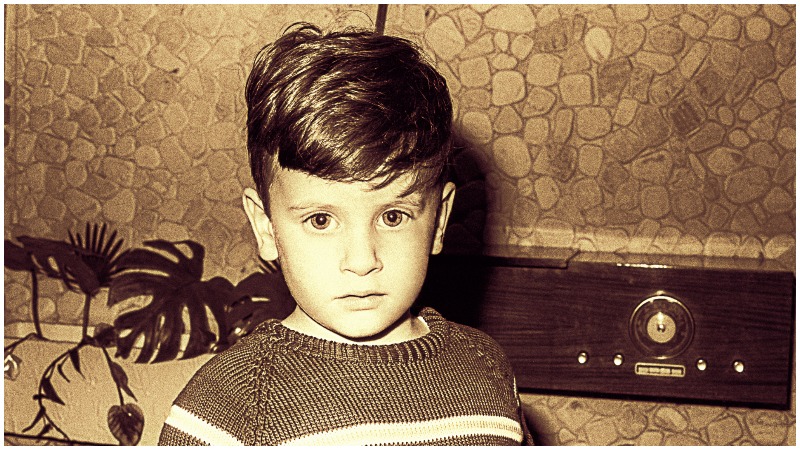

Dmitri Shostakovich was born in St. Petersburg itself. He was connected to, and part of the city. Those readers familiar with Russian/Soviet history will know that St. Petersburg was founded by Russian Tsar Peter the Great.

During the Bolshevik Revolution is was called Petrograd and in the Soviet Era which followed, it was known as Leningrad, after the “Father of Soviet Communism.” Today, it has been renamed yet again and is St. Petersburg once more.

He came from a middle-class background (which later did not help him with Soviet authorities looking for reasons to condemn him), and was a musical prodigy likely from birth. He took piano lessons from his mother but soon was playing and writing things far beyond her abilities to keep up with. When he was thirteen, just a year or so removed from the revolutionary upheaval of the Bolshevik’s, he entered the Petrograd Conservatory.

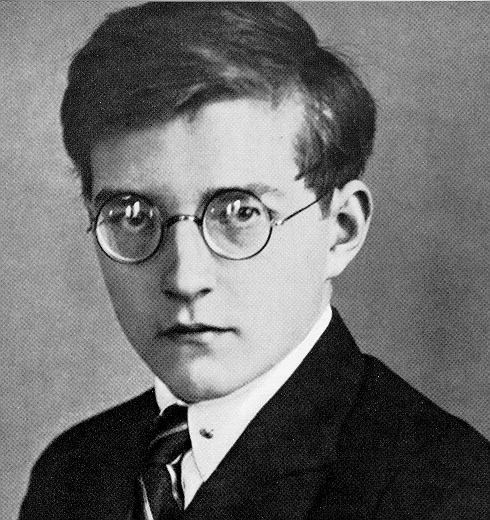

While at the conservatory, he was both admired and criticized. Instructors recognized his talent but criticized him for being too willing to copy those who went before, such as Stravinsky and Prokofiev.

Still, when he wrote his First Symphony, which premiered in 1926, he was recognized as a great young talent, and fortunately (or unfortunately) was noticed by Russian Field Marshal Tukhachevsky, a hero of the Bolshevik Revolution and the subsequent Russian Civil War. Tukhachevsky prided himself on being an educated and refined man, and personally sponsored many artists and athletes.

The Field Marshal’s wish was to elevate the masses, to lift up their culture, rather than bring the culture of Russia down to them. For a time, he was quite successful and having Tukhachevsky as a patron was a very good thing – for a time. It meant that in the unbelievably dangerous and political times of the 1920s and 30s in the U.S.S.R., you had “proteksiya” — protection.

Unfortunately, Tukhachevsky, while recognized as a great tactician and patron, was not a great politician. As Stalin rose in power, Tukhachevsky fell. Even before his death in the Great Purge of 1936-37, his star was on the wane, and anyone associated with him was suspected of working against the regime – Stalin in particular. This meant Shostakovich, among many many others.

In 1936, Stalin made two trips to the opera/symphony in Moscow that were meant to convey a very strong message. The first performance, by a little-known composer, Stalin said had “great ideological and political value.”

This little-known composer rose in the ranks of favored musicians and gained the many perks that went with it. Ten days later, Stalin again attended a performance, this time of Shostakovich’s “Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District.”

Told beforehand that Stalin would be there, Shostakovich canceled a previously arranged tour. When Stalin got up without clapping and left immediately, everyone present, especially Shostakovich, knew he was in trouble. When the show ended, Shostakovich was white as a ghost and shaking so much from fear he could barely take a bow.

Within weeks, Shostakovich’s commission dried up, his income was cut by over 75 percent, and he contemplated suicide. Naturally very nervous, and likely with a case of OCD, Shostakovich’s only reason for living was his wife and two children.

Told he was to be arrested one particular night, he waited with packed bags by the buildings’ elevators so when the police came to take him away, they wouldn’t wake his family. Many of his artist friends – writers, fellow musicians, actors – were swept up in Stalin’s purges. Many were shot. Many served time in the Gulag and never returned. Others did, but were never the same.

Desperate to find work and feed his family, Shostakovich took work writing movie soundtracks. He also went secretly to work on his Fifth Symphony, which premiered a year later.

Purposely introducing sounds that could be related to Russian folk music (representing the peasantry), and industrial sounds from horns and percussion (symbolizing the workers), the Fifth brought Shostakovich back into Stalin’s good graces. Temporarily. His 6th Symphony followed in 1939, it was a safe work, following the dictates of what good “Soviet” music should be.

Shostakovich’s most famous work, the Leningrad, is mysterious. Some of his friends and family said, after Stalin’s death and again after Gorbachev’s period of “Glasnost,” or (“openness”), the composer had begun work on the symphony before the German invasion of the U.S.S.R. and the siege of Leningrad. They say he was secretly condemning not only the rise and threat of Nazi Germany, but the totalitarianism at home as well.

Shostakovich himself said that when the Nazi invasion came and the Germans were at the gates of the city, he wrote with “an inhuman intensity I have never before reached.”, turning out page after page. The symphony is long – over seventy minutes, and Shostakovich had to be almost forcibly evacuated from the city to the interior of the country to finish its last movement.

While he was doing this, hundreds of thousands of his countrymen were dying in Leningrad – it was a horror show of artillery, starvation, disease, thirst, and cannibalism. This last has been verified in the years since the fall of the U.S.S.R.

In December 1941, two years before the siege was lifted and as German troops were at the gates of Moscow, Shostakovich finished his work. Ironically, the people of Leningrad and most of the Soviet Union did not hear the work until it was broadcast live in both London and New York. A microfilm of the score had been sent out of war-torn Russia.

Eight months after its completion, the Leningrad Symphony was played for the survivors of the siege, who still had more than two years of horror to endure. Many said after the war that the first performance lifted them up out of the city and gave them the courage to carry on – at least for a time. The work was incredibly popular during the rest of the decade and came to symbolize not only Leningrad’s fortitude but the resilience of the Soviet people, who lost over twenty million of their countrymen during the war.

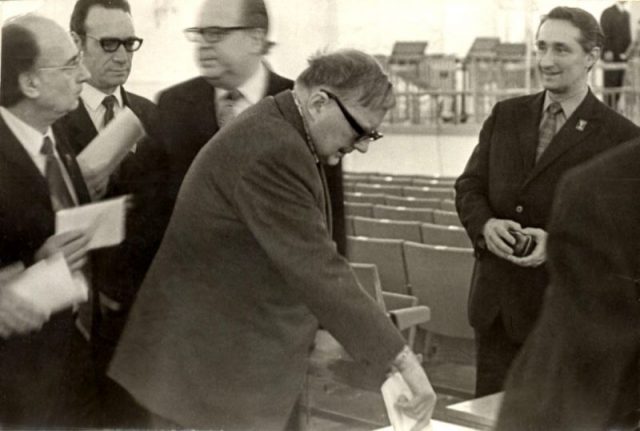

As for Shostakovich, he continued writing, completing various smaller works and eight more symphonies in his lifetime. But beginning in 1948, it looked again like he might not be able to complete anything. Stalin began another purge, for various paranoid reasons. The reason given for Shostakovich’s removal from the Moscow Conservatory (the most elite of them all) was that he wrote music with “too much Western influence.”

He was briefly rehabilitated for propaganda reasons in 1949, and was sent to the U.S. for a public tour, but was humiliated when exiled novelist Vladimir Nabokov described him as “not a free man,” and an “obedient tool of his government.” When he returned to the U.S.S.R., not having publicly fought back against this (it was true), he again was in Stalin’s dog-house.

When Stalin died in 1953, and Khrushchev slowly began to loosen some chains in the U.S.S.R., Shostakovich once again was rehabilitated. In 1960, he joined the Communist Party, a move which some friends condemned, but while in an “elected” position, he wrote works interpreted as being sympathetic with the Soviet Union’s oppressed Jewish minority.

Dmitri Shostakovich died in 1975 after a long illness.