As a general, Jan Žižka was never defeated in battle. Which makes it all the more strange that his one ambition was to be beaten. Not on the battlefield, you understand.

No, Žižka wanted his own skin to be used to make a drum to be beaten as his men marched into battle.

According to Today, I Found Out, Žižka is considered one of the finest military minds in world history.

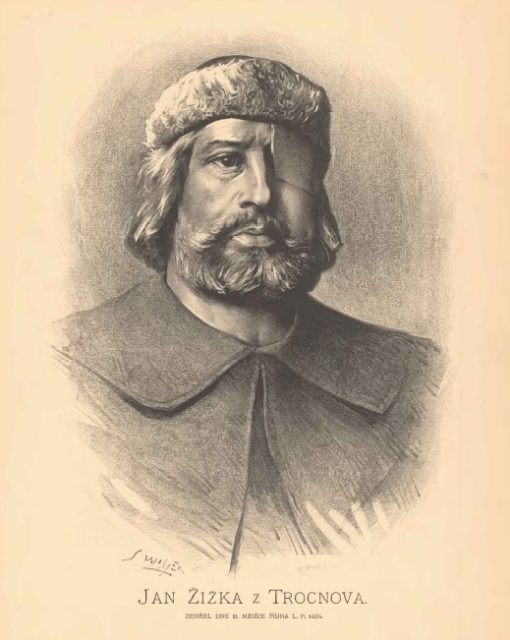

Britannica says that Count Jan Žižka’s was born in 1376. He was raised in the court of King Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia (today in the Czech Republic).

He began his military career fighting with the Poles as a mercenary and was with them at the Battle of Grunwald (also known as Tannenberg) in 1410, during which he lost an eye from a battlefield wound.

After Wenceslaus died in 1419, the king’s half-brother, Sigismund, tried to claim the throne.

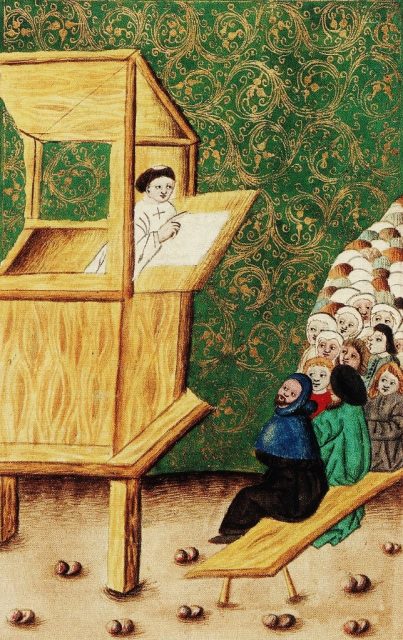

He met with resistance from the Hussites, followers of the radical theologian Jan Hus, leader of a reformation faction which had been engaged in a series of religious conflicts against the Catholic Church for some years.

By this time, Žižka had returned to Bohemia and was in command of the Taborites, a peasant Hussite militia whose tight discipline and religious fervor made them more than a match for the forces that they met.

Žižka was a brilliant commander and an original military thinker.

He utilized farm wagons to create mobile artillery centuries before the idea became commonplace. And he was the first commander to see his artillery, infantry, and cavalry as elements in one fighting unit.

Tactically, he was often forced to take a defensive position because of the difficulties of responding at any kind of speed with his heavy farm wagons; however, because of that, he mastered the art of ensuring his enemies were forced to attack from weaker positions.

Today I Found Out points out that, although cumbersome, Žižka’s war wagons played a key role in many of his victories, often in the face of what were undoubtedly superior numbers.

A major contributory factor in his success as a military commander was that as the Duke of Wellington and Napoleon some 400 years later, he had the ability to read and understand the topography of the battlefield and to take the best position.

Žižka, it seems, was no shrinking violet on the battlefield and liked to be in the thick of it, meeting his enemies face to face.

But his ruthless determination to fight with his men cost him dearly, leading to the loss of his other eye.

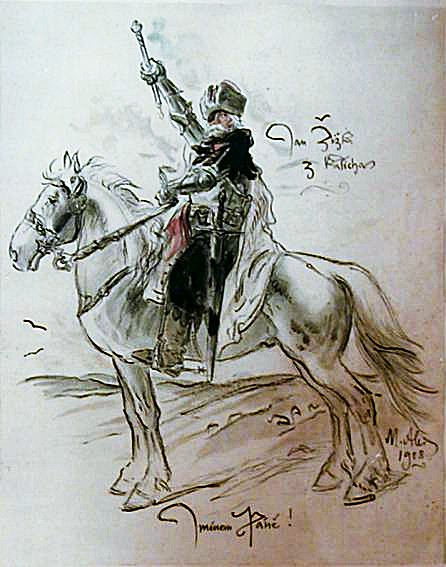

For other generals, completely losing sight might have meant it was time to call it a day, but Žižka was made of sterner stuff.

He continued to lead his army, even though he was completely blind, until his death in 1424.

It would have been fitting to note that he died as he lived — in the midst of battle. But, in fact, he died from the plague.

Before his death, however, Žižka had made it clear that his skin was to be stripped from his body and used to make a drum that his men would beat as they went into battle. Britannica recounts that for years after Žižka’s death, Hussite forces continued to defeat foreign armies that tried to invade, but they were finally overcome some 15 years later, after infighting between rival factions.

Read another story from us: The Incredible Ancient Carving Only Visible With a Magnifying Glass

Despite the evident success of his tactics in mobilizing artillery and integrating his forces, it was 200 years before Žižka’s strategy was followed by other European armies, when King Gustav II of Sweden adopted them in the 17th century. It’s unlikely, however, that other military leaders followed Žižka’s example of drumming his troops to victory even after his death.