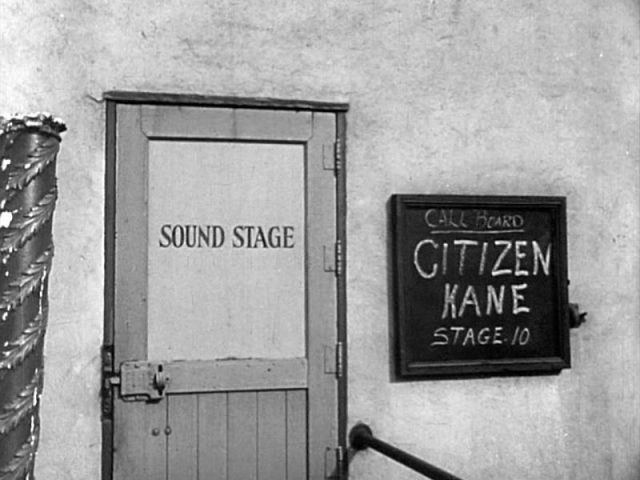

Citizen Kane, the 1942 drama made by Orson Welles, is frequently cited as one of the greatest movies ever made.

In the 76 years since its release, critical support for the film has gone from strength to strength, and historians of cinema have recognized its crucial importance in setting the agenda for filmmaking in the 20th century.

So why did this classic of modern cinematography fail at the box office?

The movie was the brainchild of Orson Welles, a rising star on the 1930s theater and radio scene.

According to the Guardian, by the tender age of just 22, Welles had earned a reputation as a powerful performer and innovative theatrical producer.

In particular, his radio adaptation of The War of the Worlds was an unprecedented success. In what may be considered the first “mockumentary,” The War of the Worlds convinced many listeners that a Martian invasion of Earth was actually underway.

On the back of this and several other critical successes on the stage, Welles made the move into Hollywood. He was able to negotiate for a greater degree of creative control than was typically awarded to filmmakers, and finally struck a deal with RKO Radio Pictures that gave him full reign over two movies. Welles would write, direct and perform, and would have the last word on the final cut of each film.

According to the Guardian, Welles had his heart set on an adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. However, the studio bosses rejected the script, and Welles was forced to abandon his idea. He then struck upon a script that had been developed by Herman J. Mankiewicz.

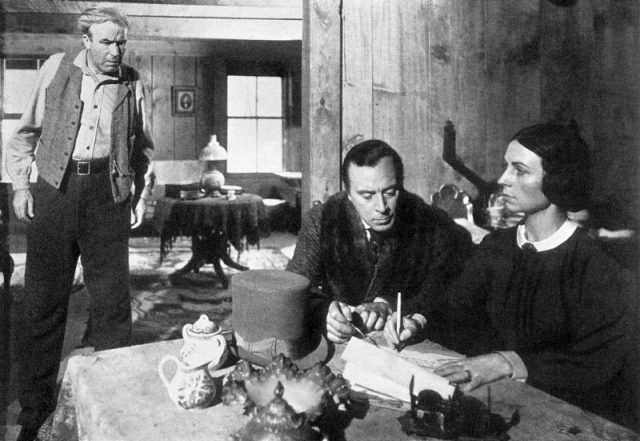

The story was a mystery drama based on the character of a real-life press baron, William Randolf Hearst. Welles and Mankiewicz collaborated on a revised script, and so Citizen Kane was born.

Welles was a completely untried director, but he surrounded himself with talented, experienced people, and proved to be an exceptionally quick learner. His lack of training meant that he was more adventurous and creative than many of his peers, and the film exploded many of the conventions of mid-20th century cinematography.

According to Mental Floss, Welles famously told his collaborator Gregg Toland that he knew nothing about film-making.

Toland replied that this was ideal, saying, “I’m tired of working with people who know too much about it.” Toland and Welles pioneered many techniques and approaches to cinematography, including composite shots and unusual camera angles, which would later become Hollywood staples.

The film also broke new ground in make-up design and special effects. Welles and his team adopted experimental new techniques using latex to achieve the look of the elderly Kane.

The approaches pioneered on Citizen Kane are still in use today, and transformed the use of make-up to achieve special effects.

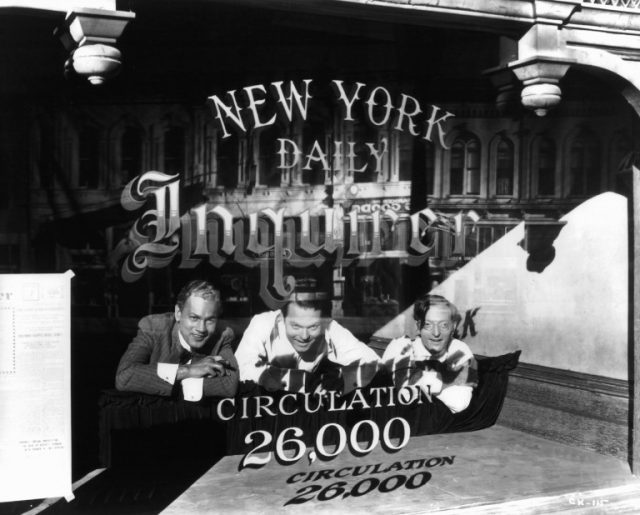

Citizen Kane should have been an overwhelming success. However, William Randolph Hearst, the real-life figure upon whom the movie was allegedly based, worked extremely hard to sabotage it. According to the Guardian, when Hearst heard about the movie, he was furious.

As a major press mogul, he had considerable power over the way in which Citizen Kane was covered in the media, and he launched a boycott in all of the outlets he had connections to. He even attempted to buy the film in order to ensure that it would never be released.

Citizen Kane was eventually released to critical acclaim, but Hearst’s boycott had done the trick. Many exhibitors refused to show the film, and at the box office, it was a financial catastrophe for RKO Pictures, which failed to recoup its losses.

The failure of Citizen Kane as a commercial venture was a huge embarrassment for the studio, particularly given the unprecedented amount of control that had been given to Welles.

Read another story from us: David Bowie Refused the Role of a Bond Villain for Some “Hidden” Reasons

He would never again be able to negotiate such a favorable contract with a Hollywood studio, and the perceived “failure” of the greatest movie of all time would haunt him for the rest of his career.