Piloting an airplane is a responsible job, and being a pilot requires a lot of training and knowledge. However, with today’s advanced technology, it’s easy to imagine that the pilot can flick on autopilot and kick back for a snooze as soon as the plane leaves the tarmac.

The reality is a lot more complex. “When we’re speeding over the globe, we are going well over 500 miles per hour, and we are in an incredibly hostile environment,” explains Nick Anderson, a London-based captain for an international airline, in an interview for Condé Nast Traveler.

Weather is one of the biggest considerations. “You can’t really sit back and relax,” says Anderson. But thanks to stable air-to-ground and air-to-air communication, pilots like Anderson able to keep in touch with both air traffic control and other aircraft, allowing them to anticipate areas of severe turbulence, for example.

And using clear, globally understood language is key to safe and clear communications — such as the internationally recognized word “Roger” which in aviation-speak means the message has been received. But why Roger?

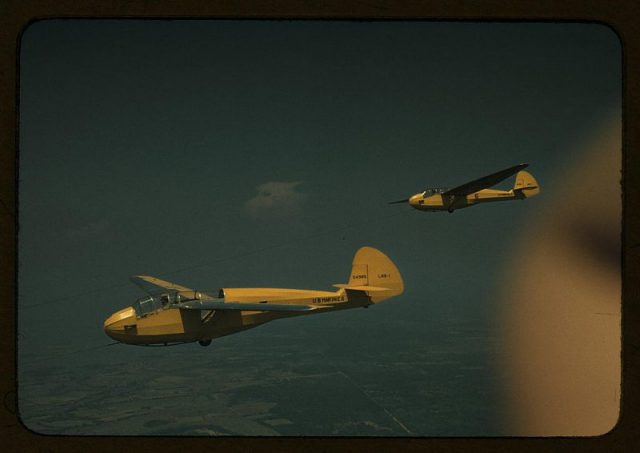

Communication has been a challenge ever since December 17, 1903, when the Wright brothers made the first successful flight in history. If there isn’t a connection between the pilot and the ground staff, it might endanger the lives of both the passenger and the aviation personnel.

According to Wonderful Engineering, during the first flight of Wilbur and Orville Wright, communication with the plane in the air was accomplished by using hand signals, colored paddles, and flares.

Over the following decade, ground-to-air and later air-to-ground transmission was made possible thanks to advances in wireless telegraphy. Pilots began to use Morse code to communicate, and the confirmation signal that a message had been received was the letter “R” in Morse code.

Finally, in 1915, the first radio communication between ground crew and an airplane in flight took place at Brooklands, England. Two way communication devices were developed by the U.S. Army Signal Corps by July of 1917.

The letter “R” was still used to mean a message had been “received and understood,” only for voice communications, American pilots began using the term “Roger” for clarity.

Since not every pilot in the world speaks English, in 1927, the International Telegraph Union designated “Roger” as a standard for all air traffic, and the term became embedded in international aviation language.

It was later incorporated into the U.S. joint Army/Navy phonetic spelling alphabet, which was introduced during World War II. It goes as follows: “Able, Baker, Charlie, Dog, Easy, Fox, George, How, Item, Jig, King, Love, Mike, Nan, Oboe, Peter, Queen, Roger, Sail (1941-43), Sugar (1943-56), Tare, Uncle, Victor, William, X-ray, Yoke, Zebra.”

Anyone who has seen the satirical movie Airplane will probably remember the quote:

Co-Pilot Roger Murdock (to Capt. Oveur): “We have clearance, Clarence.”

Capt. Oveur: “Roger, Roger. What’s our vector, Victor?”

A universal spelling alphabet — the International Radiotelephony Spelling Alphabet, better known as the NATO phonetic alphabet — was implemented on March 1, 1956, but “Roger” kept it’s status in radio voice procedure.

Among the changes from the Able-Baker system, “Roger” was replaced with “Romeo.” The worldwide adopted spelling alphabet reads as:

“Alfa, Bravo, Charlie, Delta, Echo, Foxtrot, Golf, Hotel, India, Juliett, Kilo, Lima, Mike, November, Oscar, Papa, Quebec, Romeo, Sierra, Tango, Uniform, Victor, Whiskey, X-Ray, Yankee, Zulu.”

Whatever their nationality, today’s pilots must speak an entire special language known as Aviation English which consists of some 300 words, a combination of professional jargon and plain English.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DrdrPtC6Hxk

Even though it might sound fun, the language was created to avoid potential mistakes which can result in fatal accidents due to miscommunication between air traffic controllers and pilots.

Read another story from us: The Invincible General who Wanted his Skin to Become a Battle Drum

For example, probably the deadliest accident in aviation history, the Tenerife airport disaster in 1977, in which 583 people died and 61 were injured, occurred partly because of language confusion.

Due to poor weather conditions, and Dutch and English words being confused, two Boeing 747’s collided on the runway at Los Rodeos Airport on the island.