Jordan ― a Middle-eastern country situated between Israel, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Syria ― has long been a site of extraordinary finds dating back to the very beginnings of human civilization.

A recent discovery in the Jordanian village of Beit Ras on the very north of the country brings scientists one step closer to understanding daily life in these parts during the Roman period.

A tomb accidentally discovered during road construction works in 2016 has been thoroughly examined, revealing a vivid slice of life. Apparently, the excavation project sponsored by a consortium of French, Italian, and U.S. institutions, together with the Jordanian Department of Antiquities, has come across frescoes depicting what just might be one of the earliest forms of rudimentary comics in history.

Located inside a necropolis once part of a Greco-Roman settlement of Capitolias, the writings on the wall include a strange mixture of Greek and Aramaic languages, illustrated by pictures which complete the story of life and death in a rather unromantic fashion.

Capitolias ― a Hellenistic border town which was named after its guardian-deity, Jupiter Capitolinus ― had been best known for its Roman-style theater, excavated in the early 1980s.

The discovery of the 560 square feet tomb has once again sparked interest in this hotbed of archaeological treats.

The tomb contains two burial chambers and a large, well-preserved basalt sarcophagus, despite evidence that it was most probably looted sometimes in the past.

Julian Aliquot, an archaeologist and epigraphist working on the excavation told the French news agency CNRS that the burial chambers most likely date from the 1st century AD.

He also noted that this was during the early days of the city itself, which makes the discovery even more relevant.

However, what strikes the archaeologists the most is the great condition of the paintings covering both the walls and the ceiling.

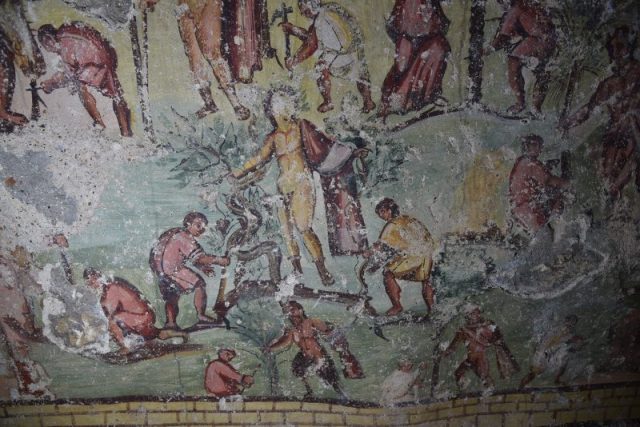

Featuring more than 260 individual figures depicted on the frescoes, the images depict both scenes from pagan mythology as well as ones belonging to the daily life of the ancient inhabitants.

Colorful panels fill the space reserved for the dead, with their depictions of gods celebrating and attending their divine banquets, and humans bringing them offerings.

gods. © CNRS HiSoMA.

There are also less religious images ― ones picturing peasants in their daily chores. Some of them are tending their fields and vineyards, while one construction worker builds a defensive wall for the city. The bigger picture here offers a full insight into the life of a citizen of ancient Capitolias ― his beliefs as well as his day-to-day life.

Regarding images which depict masonry, Aliquot commented for CNRS:

“Characters resembling architects or foremen stand alongside laborers who are transporting materials on the backs of camels or donkeys, with stone cutters or masons climbing walls, sometimes resulting in accidents.”

The series of images all form a narrative ― one describing the various phases of development of their settlement. It includes both the element of supernatural when the citizens ask for the gods to determine a suitable spot for erecting a city, as well as realistic depictions of clearing the plot and raising the walls.

The story is crowned with the depiction of a sacrifice being offered to Jupiter Capitolinus, the patron deity of this Roman outpost, as well as the patron deity of the city of Rome itself.

According to historian Pierre-Louis Gatier, who participated in the excavation project, the tomb belonged to the man who appears as the bringer of offerings in the sacrifice scene, however, his name is yet to be determined. Currently, it is presumed that the name could be engraved on the lintel of the door, which is still being cleaned.

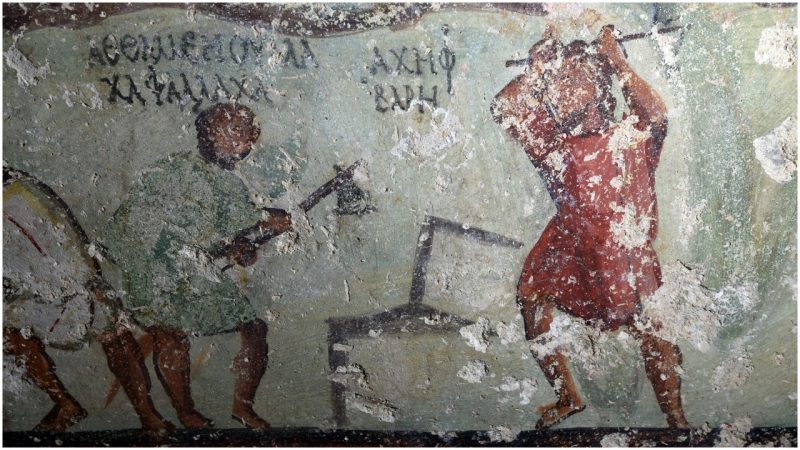

However, while the discovery of the frescoes is certainly astonishing, what makes this archaeological find so special are the writings that accompany the images. Over 60 pieces of text help determine the course of action in the narrative. The scientists couldn’t help but notice that the writings are very much in the same function as the speech bubbles found in modern comic books, as they describe a situation, follow a conversation or are addressing the gods.

For example, above one of the figures simply reads:

“I am cutting stone.”

Now, this might seem redundant, for the figure is, in fact, portrayed in an action of cutting stone. However, another picture, showing a man is accompanied by text exclaiming:

“Alas for me! I am dead!”

While the more religious features are accompanied by Greek script, these conversation-like texts are a rather unusual combination. The scientists have determined that it is Aramaic, the language widely spoken in the Middle East during the time, but written using the Greek alphabet.

What makes the inscriptions even more fascinating is that Aramaic, similar to Hebrew, has no vowels in written form, meaning that they were added in the Greek variant. This reveals interesting new facts about the common language used at the time, which found ways to merge and combine different tongues with different grammar and systems of writing.

This goes to show how such diverse life cosmopolitan settlements on the borders of ancient Judea and Syria provided for a multicultural settlement to flourish and grow, creating its own unique culture and dialect along the way.

According to Jordanian Department of Antiquities director, Monther Jamhawi, who gave a statement for the Jordan Times, the site will be open for tourists in the near future.