In 2011, when New York City police got a call one night that a dead body had been found in a lot being dug up by a construction crew’s backhoe in Elmhurst, Queens, they assumed that a new murder case needed solving. “To be called out for a DOA in this area is not that uncommon, but it’s not a frequent event,” said one police investigator later.

Very soon, though, investigators realized this was anything but a typical case.

Scott Warnasch, a city forensic archaeologist who had for several years been consumed with identifying the remains of people killed at the World Trade Center on 9/11, arrived in Elmhurst. The corpse looked fairly new to police. But after examining the body and a nearby “piece of rusty metal,” Warnash determined the person in question died some 150 years ago.

Forensic archaeologist Scott Warnasch with a 19th-century Fisk metallic burial case. Credit: Courtesy of Impossible Factual.

The woman had been buried in an iron casket, one that the backhoe apparently split open. Other facts became clear too. Warnasch said, “We quickly realized we were dealing with an African American woman, buried in some sort of white nightgown and high thick knee socks.”

Alarmingly, he also detected smallpox lesions on her body.

The excavation turned into a potential biohazard scene, and CDC experts rushed in. Smallpox once had a higher contagion rate than Ebola and cut a terrible swath through human populations. Fortunately, it was soon decided that the corpse was not a source of new contagion.

Yet the woman presented several mysteries. Who was she, and why was she buried in what experts concluded was an iron coffin?

In the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, researchers said the body was covered in smallpox lesions and that the iron coffin and its airtight environment was responsible for a “remarkable” level of preservation.

“She looked like she had been dead for a week, but it was 160 years,” Warnasch said in one interview.

Years of investigation ensued, with many answers revealed in an October 2018 episode of “Secrets of the Dead” on PBS.

CT scans and other scientific tests enabled the creation of a 3-D model of the deceased woman, to give an idea of what she looked like.

In the episode, her probable identity, achieved through study of census documents, death records, and other records, was revealed: The dead woman’s name was Martha Peterson; she was a resident of New York City and the daughter of John and Jane Peterson. She died of smallpox when she was just 26 years old.

A facial reconstruction of what “The Woman in the Iron Coffin”created by forensic imaging specialist Joe Mullins. Credit: Impossible Factual / Joe Mullins

Martha was buried in an elaborate metal casket on the property of what was once an African Methodist Episcopal church. Researchers concluded that she was placed in an iron coffin not because of attempts to protect the population from infection, but as a mark of respect and caring for her, and because of her special connection to the maker of the coffins.

“Despite the fact that she was contagious with smallpox, they still cleaned her body, dressed it, did her hair — even though this was a potentially life-threatening disease,” Warnasch said in an interview with Live Science.

During the 1850s, more than 10,000 African Americans lived in New York City, made up of slaves who had been freed since 1827 when New York State changed its law, and those who were born free.

Queens was primarily rural in the early to mid 19th century. What is now Elmhurst was then called Newtown, a community favored by black New Yorkers. The city was not safe from slavery’s reach, however. People came north in search of runaway slaves, and while in the northeast were known to kidnap free blacks and take them south, as in the book 12 Years a Slave.

There was even a Queens Freedom Trail, by which fugitive slaves escaped bondage in Southern states.

After the Civil War, a middle class of black families grew in number in Queens.

But during the entire 19th century, much of New York City was beset by infectious diseases. “You didn’t have great sanitary conditions,” one historian told the producers of the PBS show.

A smallpox hospital opened on Roosevelt Island in 1856, when New York was “an astonishingly unhealthy place,” said the historian, and the death rate from infectious disease rose higher than it was at the time in Boston.

Iron coffins enjoyed popularity throughout the United States in the 1850s. They “were manufactured for less than a decade, but during the brief time when they were available, they made quite an impression,” wrote Live Science.

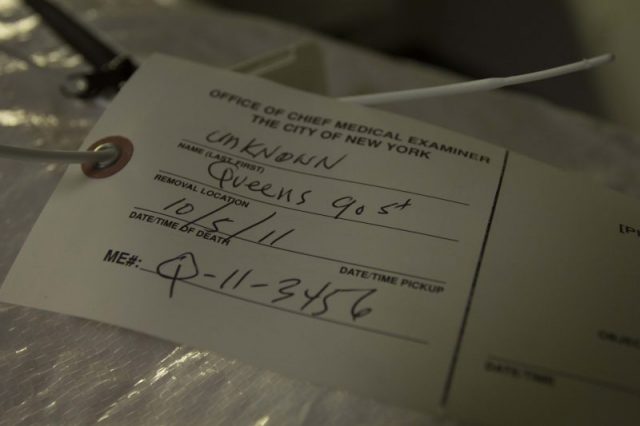

Office of the Chief Medical Examiner’s tag attached to the remains found in Queens, NY. Credit: Courtesy of Impossible Factual.

The census report said that Martha Peterson was 26 years old in 1850 and lived in the household of William Raymond, who was the brother-in-law, neighbor, and business partner of the iron coffin maker Almond Dunbar Fisk.

“The first cast iron coffin was created and patented in 1848 by Almond Dunbar Fisk, a stove manufacturer from New York,” wrote ABC.

“The so-called Fisk metallic burial cases were custom-formed to the body of the deceased, styled after an Egyptian sarcophagus, and some featured a small glass window over the face for viewing.”

Warnasch said he believes Peterson worked for Dunbar as a domestic servant. When she died, apparently either Peterson made the arrangements for her burial, or her family did using knowledge gained from her living in his household.

Read another story from us: 8-yr-old Girl Finds Ancient Pre-Viking Sword in Swedish Lake

“That’s as close to a smoking gun as you can get for the early 19th century,” Warnasch said.