“Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me.” — The Rich Boy, F. Scott Fitzgerald.

And nowhere was the disparity between the wealthy and the wannabes more vividly on display than during the appropriately-named Gilded Age of the late 19th century.

Get a gander of these over-the-top (and then some) extravagances enjoyed by the top one percenters.

Flights of Fancy

Mink was nice, silk sublime, but what really sent women into a frenzy: the pure white plumage of the snow egret, thought to be one of the most exquisite species of birds by none other than John James Audubon, noted 19th-century ornithologist and artist.

The pristine feathers were plucked during the height of the breeding season to be used by milliners to adorn fanciful hats for their toney clients.

Things got so out of hand that the snow egret was near extinction by the latter part of the century.

And it wasn’t just egrets that were in high demand: It was believed that no less than fifty North American species were being slaughtered for their feathers.

Enter two feisty Boston socialites, Harriet Hemenway and her cousin, Minna Hall, who read about the birds’ plight and made it their mission to save their feathered friends.

The two rebel-rousers rounded up other women from Boston society for a series of tea parties and convinced them to stop wearing feathered hats.

The successful boycott led to the passage of the Weeks-McLean Law, also known as the Migratory Bird Act, in 1913, outlawing market hunting and the interstate transport of birds.

24-Carat Commode

Baltimore’s Garrett clan (which made its fortune in the railroad industry) didn’t do anything by half. After industrialist T. Harrison Garrett moved his family into the massive Evergreen estate in northern Baltimore, Maryland in 1878, they decided to add some upgrades, expanding the house to 48 rooms — all the better for displaying their collections of Tiffany glass.

One notable addition was a theater—ticket window decorated by Leon Bakst, famed Russian set and costume designer for the Ballets Russes. Bakst also designed stage sets and costumes for Alice Garrett to wear during her singing-and-dancing performances for guests.

But even that was outdone by the bathroom, the centerpiece of which was a toilet seat of pure gold — truly a throne fit for a king. (Interesting tidbit: Instead of reaching for a toilet paper dispenser after doing one’s business, he or she merely pressed a call button, presumably to summon some poor servant, who lucked into one of the lousiest jobs in the world.)

Doggy Dinner Parties

During the 1900s, “anything you can do, I can do better” was the prevailing attitude, particularly when it came to entertaining.

Marion Graves Anthon “Mamie” Fish, the wife of railroad baron and socialite Stuyvesant Fish, was well known for her extravagant parties. When she threw a Dog’s Dinner birthday party for friend Elizabeth Drexel Lehr’s pomeranian, Mighty Atom, Mrs. Fish decked out her own beloved dog with a $15,000 diamond collar for the occasion.

Well-heeled guests arrived with their well-heeled pooches, bringing gifts for Mighty Atom totalling $25,000.

Other hosts found their own unique way to show off their wealth. A soiree at Delmonico’s in New York City featured an enormous indoor garden with a lake in the middle, complete with swans.

Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt brought Broadway to her estate, the Breakers, in Newport, Rhode Island, inviting the entire cast of the musical The Wild Rose to perform (the show’s sets came too).

And billionaire James Hazen Hyde decorated his home to look like the court of Louis XIV for a masquerade ball, while the Metropolitan Opera House’s 40-piece orchestra supplied the music.

Conspicuous Consumption

Money wasn’t the only thing the wealthy had an appetite for during the Gilded Age. An expansive waistline was a sign of living the good life.

And when it came to packing down food, beefy businessman “Diamond” Jim Brady was in a class by himself. William Grimes, author of Appetite City, refers to Brady as the “Paul Bunyan of the dinner table.”

Brady’s biographer, H. Paul Jeffers, described a typical dinner thusly: “two or three dozen oysters, six crabs, and a few servings of green turtle soup. The main course was two whole ducks, six or seven lobsters, a sirloin steak, two servings of terrapin and a variety of vegetables.”

For dessert, “pastries…and perhaps a five-pound box of candy.” Brady washed it all down with orange juice.

It’s said that Brady began his meals sitting four inches from the edge of the table, and kept eating until his stomach made contact. (In case you’re wondering, Brady died of a heart attack at age 61. Doctors claimed his stomach was six times that of the average person.)

Real-Estate Rivalries

Nowhere was the “show ‘em what you’ve got” mentality on display more than Newport, Rhode Island. America’s newly rich set out to mimic the lifestyle of European aristocracy.

What resulted was a jaw-dropping game of one-upmanship among neighbors and, in some cases, family members — most notably, two Vanderbilt brothers: William and Cornelius.

William Vanderbilt’s Marble House, a Versailles-inspired showplace, had no equal in opulence when it was completed in 1892, boasting walls coated in 22-carat gold leaf, a front portico designed after the one at the White House, and an 18th century Venetian ceiling painting featuring gods and goddesses from classic mythology adorning the ceiling, and $7 million worth of marble.

“Oh, it is so on…” (or words to that effect), said William Vanderbilt’s younger brother, Cornelius, who responded in kind by constructing his own showplace — The Breakers, a 70-room Italian Renaissance-style palazzo inspired by the 16th century palaces of Genoa and Turpin — to one-up his brother.

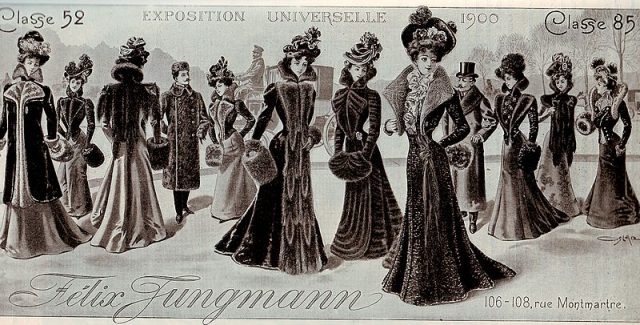

Closet Deep-Dives

When you have closets full of the latest fashions, you can’t be expected to spend the day in the same outfit. So the rich changed their clothes (at least) several times a day.

The ladies, in particular, had plenty to pick from: morning street dresses, dressing for receiving callers, carriage dresses, visiting dresses, full dinner dresses, ball dresses, hostess dresses, dresses to wear to church, to the theater, to concerts, outfits for riding, croquet, archery, skating, traveling…well, you get the idea.

However, the premiere quick-change artist may have been a man: It’s said that Evander Berry Wall once swapped duds no less than 40 times between breakfast and dinner. Clothes weren’t the only things to be regularly cast aside during the day.

All that socializing tended to tire a person out, so the wealthy were big believe in afternoon naps, so bedding was changed (at least) two or three times a day.

Dining on Horseback

Tally-ho! Anyone can throw a sit-down dinner party. The truly inspired served meals on horseback.

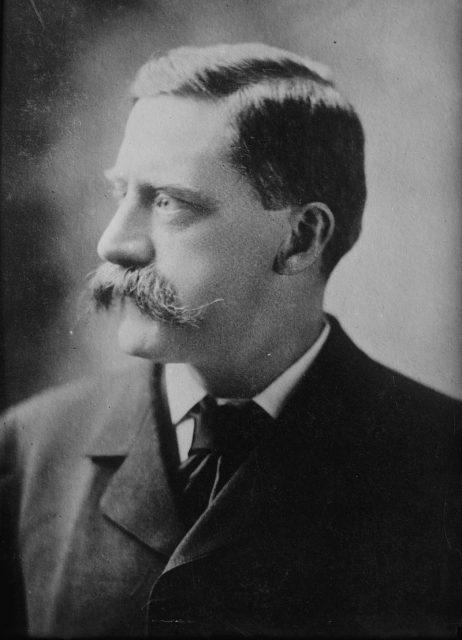

In 1903, C.K.G. Billings, a millionaire and horse-racing aficionado known as “the American Horse King,” spent $350,000 turning a Manhattan ballroom into a show ring of sorts.

Billings, an equestrian, had put the finishing touches to a swanky private stable near Harlem River Drive and wanted to celebrate.

Guests arrived at Sherry’s a 5th Avenue restaurant decked out in evening duds, only to get the shock of their lives.

Tables had been cleared from the room, replaced with fake turf and scenery resembling an English countryside.

Party-goers were instructed to hop onto horses (which were hoisted up in a freight elevator). Waiters placed a series of elaborate fare, such as caviar, turtle soup, rack of lamb, guinea hens, flambéed peaches, and Krug champagne (or ginger ale for those who didn’t want to get sauced and tumble from their mount) on table trays attached to each horse’s saddle.

As a momento of this most unusual evening, guests (who were, let’s face it, good sports) were given sterling-silver horseshoes inscribed with the menu.

Pimped-Out Private Railroad Cars

Apparently, you can take it with you. Engineer, industrialist, and the founder of the Pullman Company, George Pullman made traveling by train a luxurious experience in the 1800s, with the introduction of sleeping cars, dining cars, and parlor cars.

To cater to uber-wealthy clientele, the company took things to another level with private rail cars, which featured four-star, hotel-like accommodation, including chef and personal assistants.

The cars, which attached to commercial passenger trains, could sleep up to twelve, and could be customized to cater to the owners’ whims. There were drawing rooms adorned with custom-wood paneling, dining rooms with elaborate domed ceilings, and staterooms with queen-sized beds that connected to marble baths.

Read another story from us: Women Used to Take Their Husbands to Court for Being Impotent

One private Pullman featured a fireplace in the lounge. While some patrons owned their own private cars, others chose to rent executive charter cars instead, including then-President William McKinley and Robert Todd Lincoln, Abe’s eldest son, who became President of the Pullman Palace Car Company from 1887 to 1911.