There is a large bronze statue in London, England, on the western side of Westminster Bridge. It features a woman standing confidently in a war chariot, carrying a spear, arms raised above her head. Two more female figures kneel behind her, looking over the sides of the chariot, their faces hesitant, almost as if they’re afraid of what’s ahead. The horses pulling the chariot at rearing up, ready to charge forward. The statue is called Boadicea and Her Daughters and commemorates the feats of Boudicca, Queen of the Iceni, against the Roman Empire.

Boudicca, Queen of the Iceni

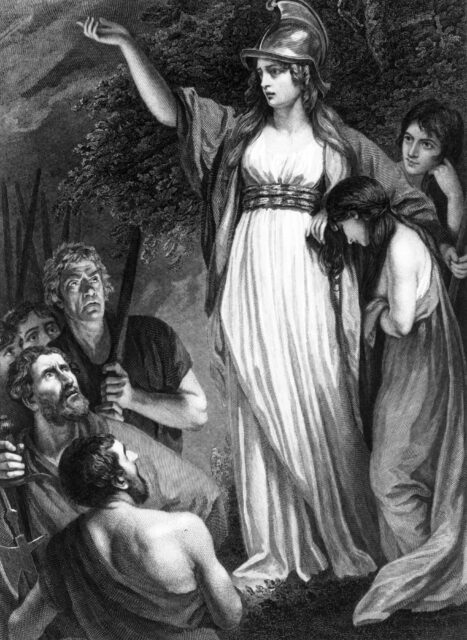

Boudicca (also spelled Boudica or Boadicea) was the Celtic Queen of the Iceni tribe, who lived in what is now Norfolk. Roman historians Tacitus and Cassius Dio both described Boudicca as a tall woman with long red hair. According to Cassius Dio, “She was huge of frame, terrifying of aspect, and with a harsh voice. A great mass of bright red hair fell to her knees.”

Her husband, King Prasutagus, was an ally of Rome. However, when he died without a male heir in 60 AD, his estate was left to Emperor Nero with his daughters as co-heirs. The idea was that this would give imperial protection to his family and land holdings.

However, contrary to Prasutagus’ wishes, Rome annexed his land and plundered the chiefs of the Iceni, thereby rescinding their alliance status. When Boudicca objected, her daughters were raped and she was publicly stripped and beaten, according to Tacitus. Resentment among the Britons at the time was already high and these actions certainly did not help.

Boudicca’s retaliation

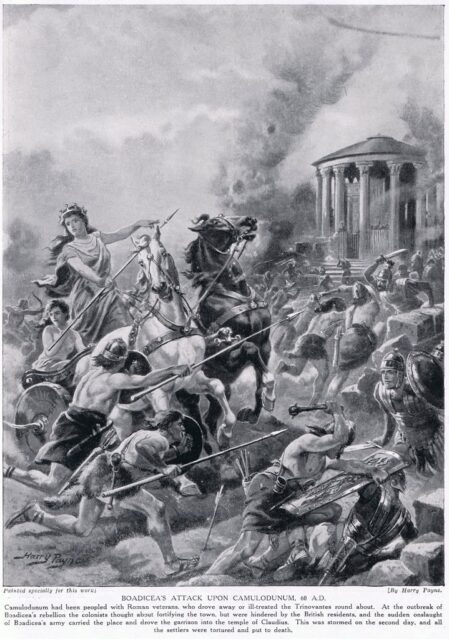

Not content to sit back and let the Romans have their way, Boudicca launched a revolt. As Tacitus wrote, “It was against the veterans [the Roman legions] that their [the Iceni’s] hatred was most intense. For these new settlers in the colony of Camulodunum drove people out of their houses, ejected them from their farms, called them captives and slaves.”

Boudicca gathered the Iceni and their allies, the Trinovantes, as well as other tribes, and captured Camulodunum (modern day Colchester), which was also the former Trinovantian capital. The town fell in two days, and was methodically demolished. The future governor Quintus Petilius Cerialis tried to save the city but was defeated, and his infantry wiped out.

News of the revolt soon reached the Roman governor, Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, in London, which was a relatively new city at the time. Tacitus again describes events saying, “Suetonius, however, with wonderful resolution, marched amidst a hostile population to Londinium, which, though undistinguished by the name of a colony, was much frequented by a number of merchants and trading vessels.”

Uncertain whether he should choose it as a seat of war, as he looked around at his scanty force of soldiers and, remembering how the rashness of Petilius had been punished, he resolved to save the province at the cost of a single town. The tears and weeping of the people, as they implored his aid, did not deter him from giving the signal of departure and receiving into his army all who would go with him. Those who were chained to the spot by the “weakness of their sex,” or the infirmity of age, or the attractions of the place, were cut off by the enemy.

Boudicca’s rebellion captured many towns

Boudicca led her rebellion into Londinium and burned it to the ground, killing anyone who had not left with Suetonius. To this day, archaeologists can still find a thick red layer of charred material throughout ancient London that clearly marks the boundary in time before and after the rebellion of 60 AD. The rebels next marched to Verulamium (modern day St. Albans), and destroyed it as well.

In all, some 70,000 Romans and Roman sympathizers were killed in the rebellion, as, according to Tacitus, the Britons had no desire to take prisoners – they were only interested in slaughter. Cassius Dio is more graphic, stating that the noblest Roman women were impaled on spikes, with their breasts cut off, “to the accompaniment of sacrifices, banquets, and wanton behavior” in sacred places, including the groves of Andraste, a Celtic goddess invoked by Boudicca during her fight against the Romans.

The battle between Boudicca and Suetonius

Suetonius finally decided to challenge Boudicca and met her in battle at an unidentified location in 61 AD. Tacitus wrote that the Britons arrived at this site in unprecedented numbers. “Their confidence was such that they brought their wives with them to see the victory, installing them in carts stationed at the edge of the battlefield.” But Suetonius had chosen the site carefully, and the Britons were pushed together in the narrow field, making them easy marks for the Romans.

The Britons fell back, and the Romans advanced in wedge formation. A supply train at the rear prevented their escape, and the Battle of Watling Street, as it has come to be known, became a massacre. Boudicca and her daughters escaped but died shortly thereafter, likely by poison to prevent them from being taken prisoner.

Read another story from us: The Magical Underground City Carved Entirely out of Salt Rock

The Britons raised smaller insurrections after the rebellion, but none gained as much support as Boudicca’s, and Rome continued to hold Britain until 410 AD. Boudicca, however, became a folk hero, and a symbol of freedom and justice, particularly during the Victorian era when her statue was commissioned.