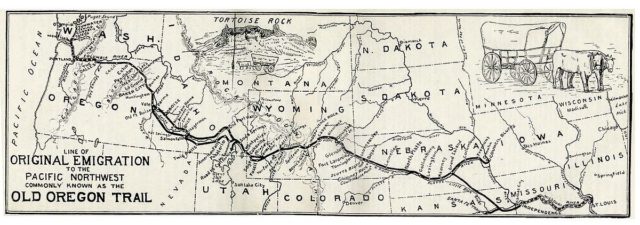

The Oregon Trail extended at almost 2,200 miles and led American settlers of the 19th century to the West in their quest for new and better life.

The trail snaked through mountains and valleys, through rivers and springs — the very territories of Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho, and Oregon today. Independence and Kansas City were some of the most frequent starting points for those who decided to move.

Fur traders were first to set down the trails, though were often not passable by wagon to begin with.

Missionaries guided by their calling to spread Christianity to the West and among the indigenous populations proved this territory was ultimately reachable.

Missionary Marcus Whitman led one of the first prominent groups on the long and dangerous road. Some 120 wagons gathered, about a thousand people and their livestock, and commenced on a five-month journey with Whitman in the spring of 1843.

A few years later, the 1850 Oregon Donation Land Act, which in essence encouraged the settlement in the territory of Oregon, triggered a tidal wave of settlers eager to get their own piece of land.

Needless to say, the trail was a challenge. Sometimes journeys lasted for almost a year.

Before setting out, the settlers usually sold all their property, closed down any active businesses and got rid of any valuables they weren’t able to carry on the road.

Preparations also entailed securing enough flour, sugar, salt, coffee — stuff that couldn’t be obtained once the trip began. Guns and ammunition stocks were also priorities, in case of dangers that lay ahead.

With fully loaded covered wagon carts, roughly half a million American settlers progressed through the Old Oregon Trail. Some of the traces they left on the road can be spotted even to this date, such as Wyoming’s Guernsey Ruts. At the Deep Rut Hill, pioneers were traversing across soft sandstone. Little by little the thousands of wheels wore down the rock, carving ruts as deep as five feet.

The paths to reach Oregon slightly altered here and there, though the majority of settlers followed more or less the same route to reach their destination.

After crossing the Great Plains they arrived at the Fort Kearney trading post. Settlers then followed the Platte River for about 600 miles before reaching Fort Laramie.

Next were the Rocky Mountains, with boiling temperatures during the days and freezing cold at night. Downpours of rain were frequent and this was an additional hardship for everyone on the road.

If Independence Rock was reached by mid-summer this was comforting. It meant the traveling group was on time and half way through the ordeal.

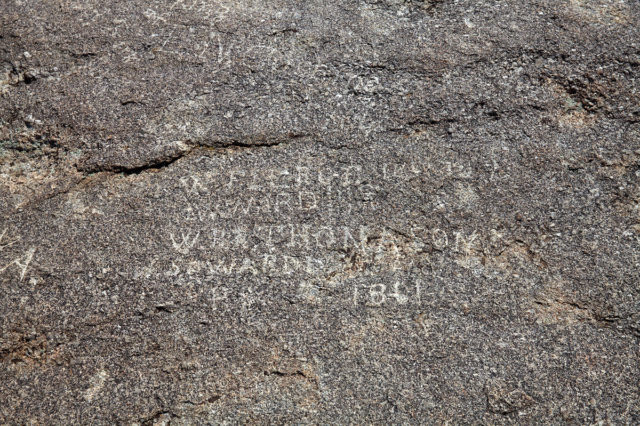

Independence Rock is among the most famous relics on the trail. The gigantic granite monolith still contains the names of thousands of settlers who passed through the area and inscribed their name on the rock. The site is also called the “Great Register of the Desert.”

Names were also chiseled on Register Cliff which is closest to the town of Guernsey. This was another important checkpoint on the road that assured pioneers they were still on course and not heading towards impassable mountainous areas.

Checkpoints like this also served as resting points, where camps were set, food was cooked on a campfire and animals were pastured.

More name carvings can be further traced on Names Hill in western Wyoming or Alcove Springs in Kansas, among other places.

Wagon tracks are also visible at few other places besides Deep Rut Hill. At Montpelier, Idaho, settlers needed to ascend the steepest hill of all on their journey — Big Hill. It was a challenging climb and even more challenging descent. Wheel tracks can be seen both on the way up and the way down.

Seven miles of wagon ruts can be seen near the National Historic Oregon Trail Interpretive Center on Flagstaff Hill. From here pioneers could catch their first sight of Baker Valley. Some of the surviving tracks are parallel to one another, suggesting the wagons were in rush to reach Powder River. The slower moving wagons were outpaced by the faster.

While some wagons finished their journey to Oregon City, others diverted to the south and settled in California. California was an exceptionally popular end destination during the Gold Rush years.

Not everyone who made this arduous journey from east to west survived many hardships on the road. Some pioneers fell to diseases they contracted while others met a violent end at the hands of hostile Native American groups whose traditional life was disrupted by the newcomers.

According to History, roughly one in every ten people died on the trail. Families did not have much choice but to bury their deceased loved ones beside the trail and resume their journey.

Read another story from us: Mitchell WerBell – The Man Who Was Involved in Everything

Had it not been for the Oregon Trail, it would have taken a lot more time for pioneers to inhabit the American West in the 19th century. The legacy they left on the trail lives on.