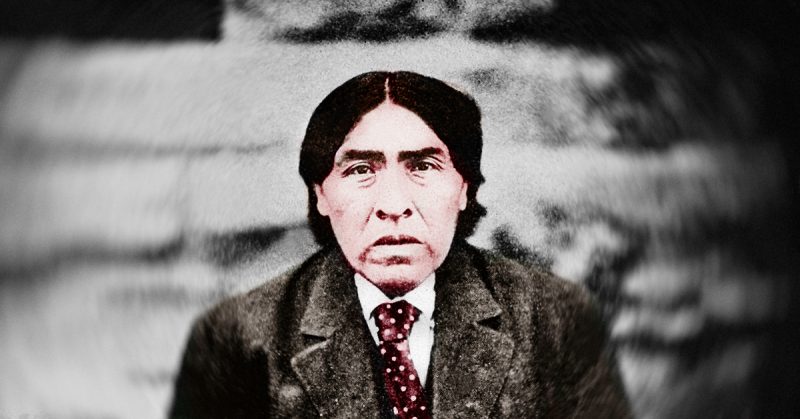

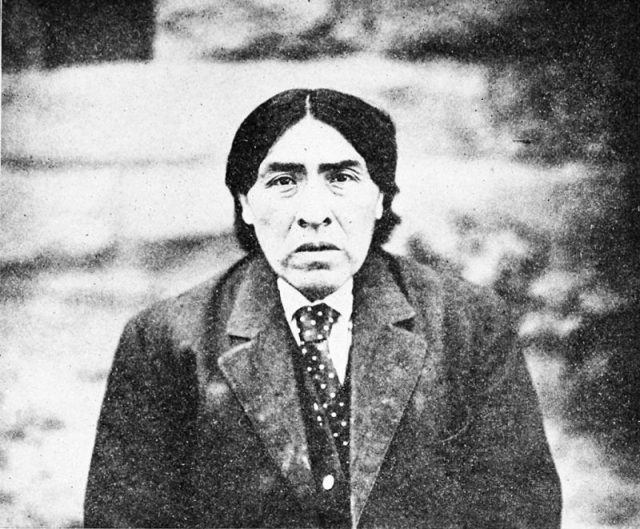

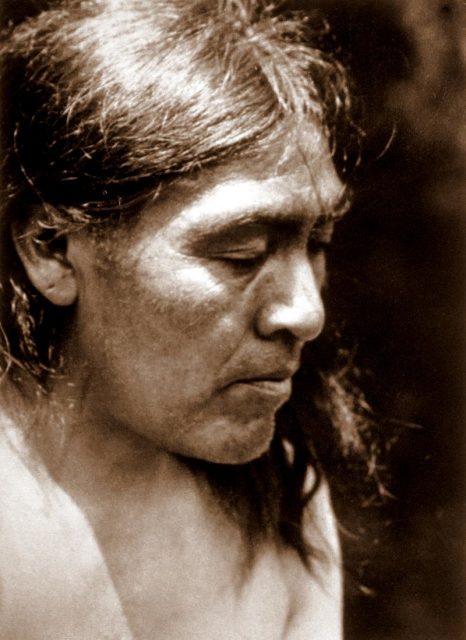

In August 1911, a starving Native American man walked out of the woods and into Oroville, California.

He was identified by two University of California anthropologists as the last member of the Yahi tribe, native to the Deer Creek area, according to UCSF.

When he emerged, thin and sooty from fires that had burned through the nearby forests, he was lost, in a very fundamental sense — far removed from the world he knew or understood.

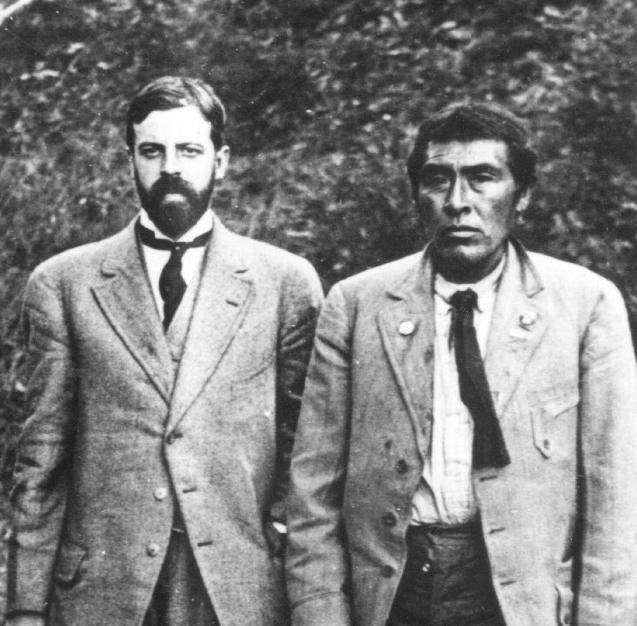

The anthropologists who identified his tribe, Alfred Kroeber and T. T. Waterman, took him back to live on the Parnassus campus and mostly to protect him from the modern and very unfamiliar world.

They named him Ishi, which just means “man” in his native language.

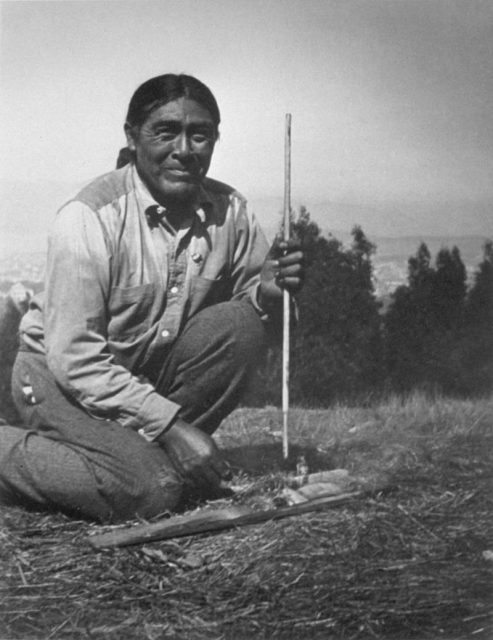

For the four years until his death, Ishi worked with UC doctors and anthropologists, showing them how he made tools and hunted, and he told them his tribe’s stories and songs.

Ishi became a media splash — people were fascinated by the “last wild Indian” and his reactions to all things 20th century.

Records from that period demonstrated that there was a mutually respectful relationship between him and his observers, and Waterman himself referred in his writings to Ishi’s “gentlemanliness, which lies outside all training, and is an expression of inward spirit.”

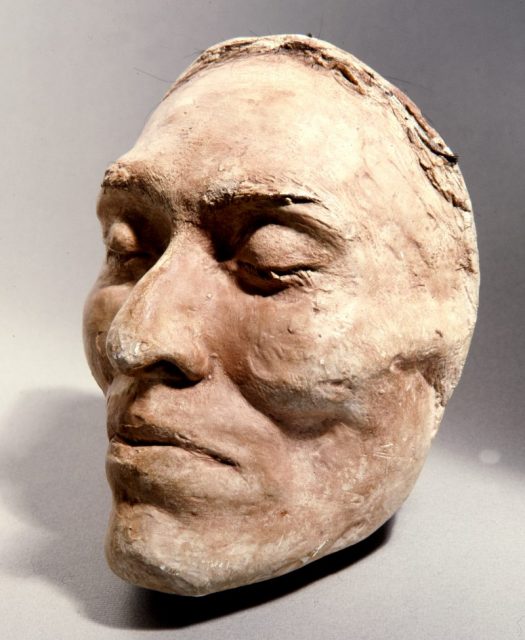

Ishi contracted tuberculosis, however, and after a number of hospitalizations and treatments, he died in 1916.

Against the wishes of his friends from the university, his body was autopsied and his brain preserved before they gave him the Christian burial they felt he deserved. However, Ishi lost everything he valued well before he wandered out of the woods near Oroville.

In 1848, James W. Marshall discovered gold in the water wheel at Sutter’s Mill, and triggered the biggest mass migration in modern history: the California Gold Rush.

That discovery brought around 300,000 people streaming into California hoping to strike the mother lode.

In just two years, the developing town of San Francisco saw population growth from a mere 1,000 to 25,000 as people streamed in to look for gold.

It only took about those two years for the easy gold to be snapped up. Miners were having to move into increasingly remote areas, which brought them into the places where the Native Americans made their homes.

Mining efforts began disrupting the ecosystems, polluting the water, and dispersing the game that the native people relied on for survival.

Miners from other places brought diseases with them that the Native Americans had never encountered, such as measles or smallpox.

The Native Americans were left ill and with a constantly shrinking supply of food.

Those tribes that fought back against the intrusions were at the mercy of the new settler’s guns, and counter attacks from the newcomers laid waste to villages.

Some places even set bounties on the Indians.

By Yahi custom, introductions had to be conducted by a third party. People couldn’t offer their own name; it had to be spoken first by someone else.

When Ishi was asked his name after he emerged from the wilderness, he would only say “I have none, because there is no one left to name me.”

When he was born, sometime in the early 1860s, the Yahi tribe, with its 400 members, was already declining.

The Yahi were close enough to the mines that they were one of the first tribes to encounter the settlers.

The streams were rapidly losing the salmon that was a staple of the Yahi diet, leaving them hungry, and those that starvation didn’t kill were lost to Indian hunters such as Robert Anderson.

Ishi and his family survived Anderson’s raids on their village, along with a few others, and they moved to Deer Creek and formed a small new settlement.

The members of the settlement kept their heads down and tried to avoid notice, in hopes that they could avoid being raided.

However, by the early 1870s the Yahi were wiped out, and Ishi and his family hid at Deer Creek. Eventually everyone else had died and Ishi was alone.

Read another story from us: Goin’ Out West! The Oregon Trail as it Looks Today

Today, California children learn Ishi’s story in school as a testament to the state’s lost history and to the Native American man who was caught between two worlds.