If we turn back the clocks to 1893, we see that the pledge of allegiance and the World’s Fair share a surprising history.

The World Fair of 1893, then known as the Columbus Exposition, is historically significant because not only did it commemorate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the New World, it was the first great Expo to feature the electric dynamo engine and the Ferris wheel, bringing the dreams of electricity to the American people.

It was also the home to the first recital of the Pledge of Allegiance.

The idea for the pledge came from Francis Bellamy, an ordained Baptist minister turned adman who worked for a magazine called Youths Companion.

In the year leading up to the opening ceremony of the 1893 Columbus Exposition, it was part of Bellamy’s job to create patriotic programming for schools that tied in with the opening ceremony being held in the winter of 1892.

By all accounts, Bellamy had quite the way with words, and he convinced Congress to endorse a national school ceremony that coincided with the opening of the Columbus Exposition.

Bellamy also convinced President Benjamin Harrison to endorse Columbus Day, but that’s another story.

With the backing of Congress, Bellamy went on to create the phrase that we now know as the Pledge of Allegiance.

The idea behind the ceremony and the pledge related to it came from Bellamy’s background in social activism.

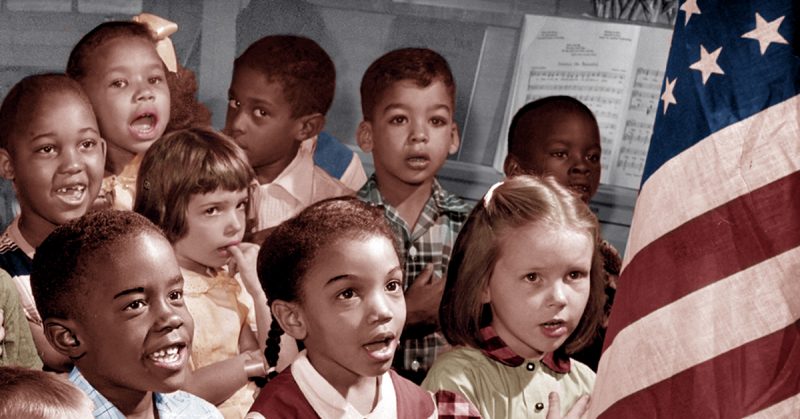

Bellamy wanted a ritual that promoted unity not just for a nation still healing from the Civil War but also something that would inspire allegiance to the American ideals of freedom and civic responsibility for those who were arriving from distant shores.

For the opening ceremony of the World’s Fair in October 1892, millions of children across America recited the Pledge of Allegiance for the first time.

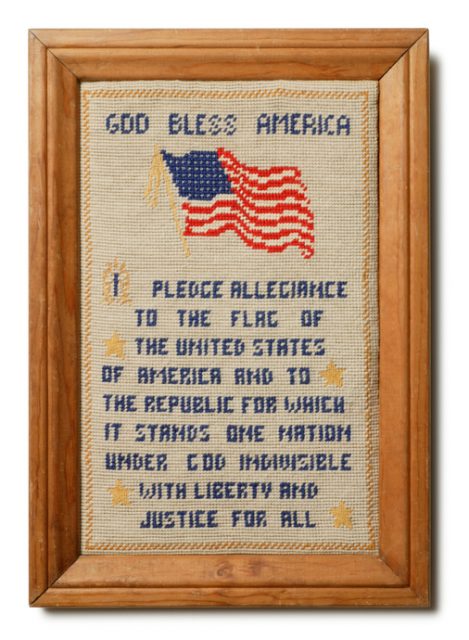

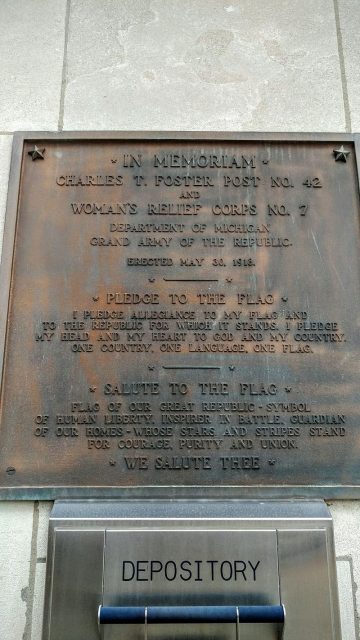

The original pledge spoken on that day was “I pledge allegiance to my flag and the Republic for which it stands, one Nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

As time went on the pledge became a powerful symbol and alterations were made to its original wording. The changes of 1923 and 1924 added “the flag of the United States of America” where the phrase “my flag” originally sat, and by 1941, when the U.S. joined World War II, the pledge had become part of the national flag code of the United States.

Although Bellamy was an ordained Baptist minister, the words “Under God” were not added to the pledge until 1954.

America of the 1950s was a paranoid place; the Cold War was already a decade old, and Senator Joe McCarthy was taking center stage with his anti-communist rhetoric.

From this air of suspicion came a call to make the pledge of allegiance something distinctly American, that is, something distinctly more religious.

The request for the addition of “under God,” however, may have been ignored by history if not for a few fortunate twists of fate.

In downtown Washington, there is a small church where Abraham Lincoln attended Sunday Mass during his presidency and each year, the Sunday before Lincoln’s birthday; this church holds a special service to commemorate the 16th President.

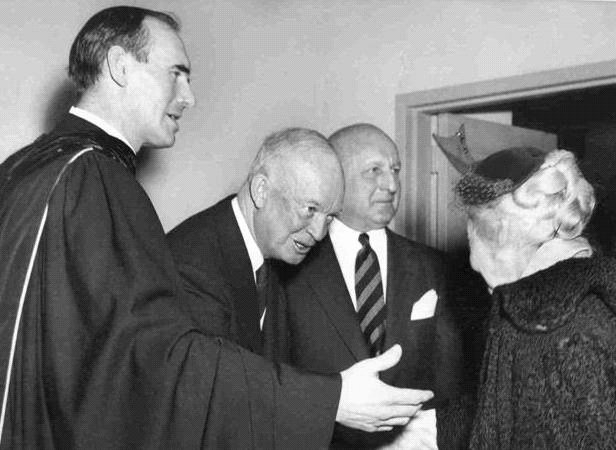

During the 1950s, Lincoln’s local church was under the care of the Presbyterian priest, Rev. George M. Docherty, a Scottish born pastor and a staunch anti-communist. A committed man of God and a fiery orator, he became the figurehead of the drive to get the words “under God” added to the Pledge of Allegiance.

On February 7, 1954, Pastor Docherty delivered his commemorative Lincoln sermon to a captivated audience. Among the parishioners that day was the most important man in America, President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

In his sermon, Docherty aggressively argued that “To omit the words ‘under God’ in the Pledge of Allegiance is to omit the definitive factor in the American way of life.” In his unapologetic view, “an atheistic American is a contradiction in terms, if you deny the Christian ethic, you fall short of the American ideal of life.”

Read another story from us: The 50-Star American Flag was Designed by a High School Student

These words resonated with the President and the phrase “under God” was added to the pledge of allegiance no less than four months later. Speaking of the event afterwards, Docherty said: “I could hear little Muscovites recite a similar pledge to their hammer-and-sickle flag with equal solemnity.”