Until the early 1900s came along, if you wanted to take a trip of any distance in the United States, you had to saddle up.

Yep, we’re talking about horse-drawn carriages and buggies. By the early 1910s, a different kind of horsepower hit the road — and in a big way, eventually outnumbering their carrot-munching counterparts.

In 1909 there were 200,000 motorized cars in the U.S.; by 1916, the number had mushroomed considerably, to 2.25 million. Not surprisingly, bedlam prevailed.

There were no stop signs, traffic lights, lane lines, brake lights, driver’s licenses, or posted speed limits.

Driver’s Ed didn’t exist (Missouri didn’t require driving tests until 1952). Drinking and driving? Not that big a deal.

Pennsylvania, in 1909, was the first state to set a minimum driving age (18 years). Before then, children as young as 11 or 12 could slide behind the wheel of the family car. U.S. highways didn’t even have center lines until 1911 — good move, Michigan!

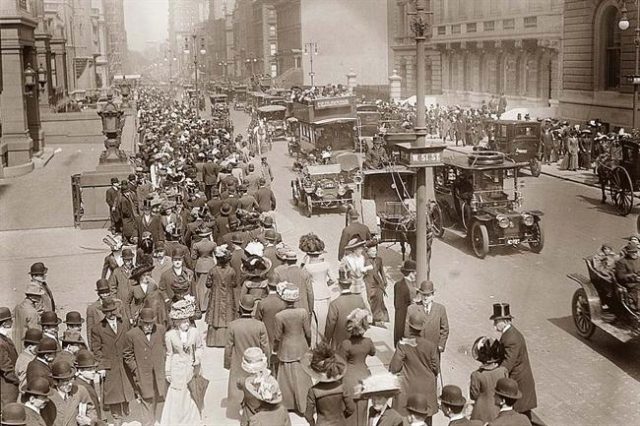

And then, there was the traffic: cars, buggies, bicyclists, streetcars, and pedestrians, all fighting for the right-of-way.

Autos would eventually win out, with drivers engaged in all sorts of hair-raising maneuvers.

Motorists parked wherever the heck they wanted, even smack-dab in the middle of intersections and “cut corners,” making sharp left turns at intersections, much like we make right turns today, hitting pedestrians and cars in the process.

Auto-inspired slang became part of the vernacular: hit and run, joyriders, road hogs, Sunday drivers, and juggernauts (out of control cars that plowed through crowds of people).

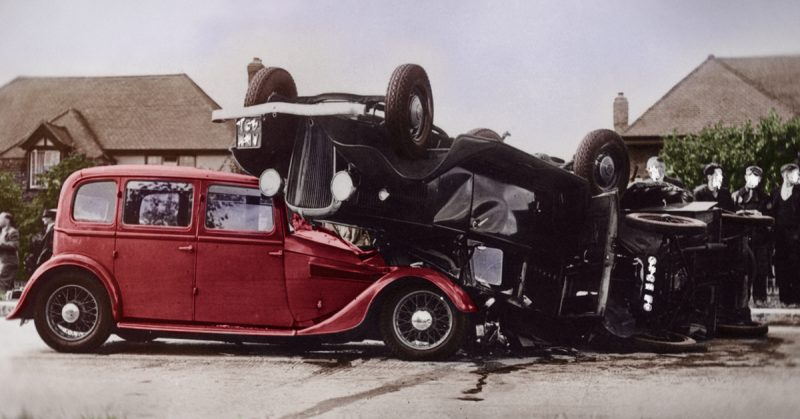

But the main cause of accidents in the early 1900s was speeding. Compared to the plodding pace of carriages, being able to whiz along at a “speed” of up to 20 miles an hour was exhilarating and drivers took full advantage — hitting corners at high speeds, which often caused their cars to skid, “turn turtle” (slang for flipping over), or smash into other road users.

Read a 1919 edition of the Detroit Free Press: “Screaming pedestrians were scattered like ninepins …some were bowled over or tossed against storefronts. [The driver’s companion], evidentially frightened by the cries of the crowd, leaped from his seat and running swiftly disappeared into the darkness.”

People hopping off of streetcars would have to race through a tangle of cars, trucks and horse-drawn, before reaching the (relative) safety of a sidewalk.

In 1901, Connecticut became the first state to pass an official speed limit: 12 mph in cities and 15 mph on rural roads. But up until 1930, a dozen states allowed drivers to go as fast as they wanted.

By 1917, the city of Detroit and its surrounding suburbs had an estimated 65,000 cars on the road, resulting in 7,171 accidents (168 of them fatalities).

Three-quarters of the victims were pedestrians. Even more disturbing: the number of children struck and killed as they played in the street. In the 1920s, 60 percent of fatalities nationwide were children under the age of nine.

The courts and police initially came up with a simple solution: have the speed limit for cars mirror the pace of horse-drawn wagons (about five miles an hour).

But the speed was so slow that automobile owners had a devil of a time keeping their cars from conking out. It was time to bring in the big guns — namely, the police.

But even the men in blue couldn’t handle this growing problem. In one afternoon in 1911, police hauled in no less than 450 people on speeding charges! By 1916, a quarter of the Detroit police force was being used to handle traffic.

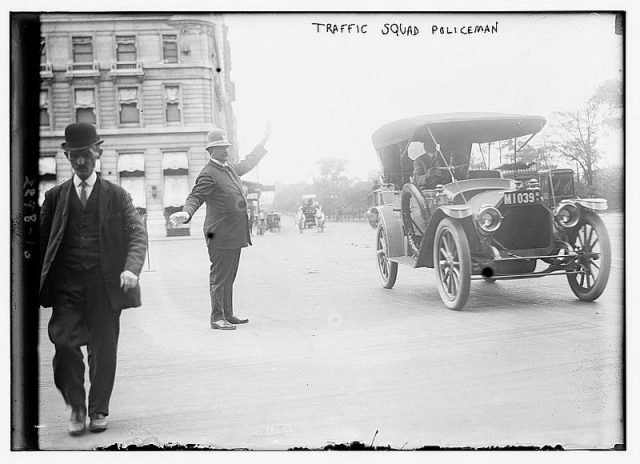

One program employed by the big cities was dubbed the Traffic Squad, a rotating group of policemen, who used hand signals to control traffic…which only confounded the general public.

Wrote one exasperated reporter in a Detroit newspaper, circa 1916: “The drivers who happened to notice the signals of the officers did not seem to understand what was wanted and drove by, making it necessary for the traffic officer to run after them and explain the meaning of the signal. The officers had to show considerable patience.”

After World War I, the accident rates continued to soar, and drivers were being demonized in newspapers as “remorseless murderers.” Reckless types were even pulled from their cars by angry onlookers.

Some believed the automobile was an instrument of evil. The state of Georgia’s Court of Appeals wrote: “Automobiles are to be classed with ferocious animals and … the law relating to the duty of owners of such animals is to be applied … However, they are not to be classed with bad dogs, vicious bulls, evil-disposed mules, and the like.”

In 1919 Detroit, bells rang out twice a day at churches and City Hall in memory of the victims of auto fatalities.

Teachers would read to students the names of classmates who had been killed by cars.

Safety parades, a phenomenon started in the 1920s, brought home the consequences of the careless driving.

Thousands of spectators watched as wrecks of cars were towed down the street with signs that read “Follow this one to the cemetery.” Some featured mannequins: Satan, behind the wheel, with his bloody, ill-fated passengers riding shotgun.

Crippled children, victims of collisions, sometimes rode in the back of open cars, sadly waving to the crowd.

Finally, in the mid-1920s, Herbert Hoover, the then-U.S. Secretary of Commerce, took action. Car manufacturers introduced safety features (turn signals, brake lights, and headlights, among them). States started instituting driver’s exams and judicial courts began handling traffic violations.

Pedestrians were held accountable, as well, for causing accidents with jaywalking. A system was put in place whereby they would cross streets at designated corners.

Read another story from us: Red Means Stop! The Curious History of Traffic Lights

Officials also found a way to control traffic, with much less manpower. Stop signs, for one thing, became commonplace, as were traffic lights, invented by Lester Wire, a policeman, and first installed in Cleveland, Ohio in 1914.