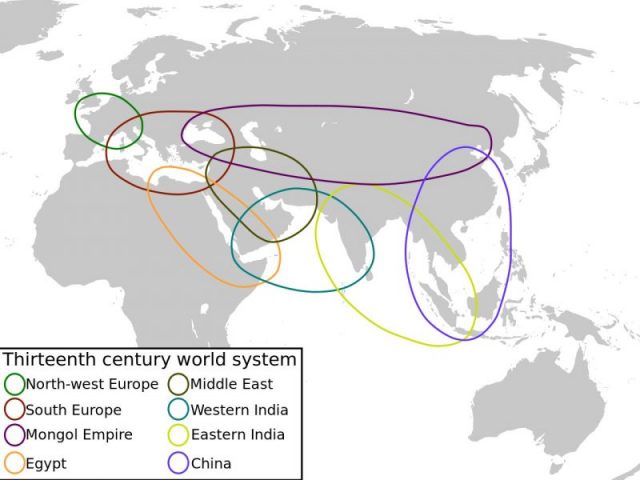

Beginning in the 3rd century BC, during the rule of the Han dynasty in China, the legendary Silk Road was the major trade link between east and west for hundreds of years, transporting imperial goods and providing cultural and diplomatic ties between the realms of Europe and Africa with those in Asia.

Being a vital economic and strategic point, the route fell into different hands over time and was often the matter that defined the power of various Asian warlords.

However, by the 13th century, it was all but abandoned. Great turmoil, wars, and pillaging had made the Silk Road unsafe for travel, and rarely anyone dared cross it without an armed escort. That is until the Mongols took the reins.

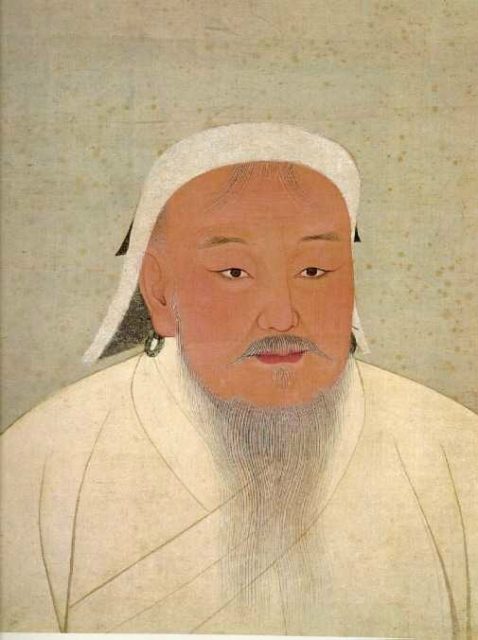

During the rule of Genghis Khan, a large part of the network was tightly controlled, for the Mongol conqueror had a great interest in limiting free trade and enabling his military budget to expand as much as possible.

Genghis Khan began controlling the northern parts of the Silk Road during his early conquests, spreading his power and influence to the south.

Destroying and occupying Arab and Turkic trade centers, he quickly gained control over the majority of the route.

Among the cities that had been utterly destroyed by the Mongol invasion was the Achaemenid Persian city of Merv, whose entire population of 700,000 was massacred in 1221, by the hand of Tolui, one Genghis’ sons. The Persian historian Juvayni described the capture of the city:

“So many had been killed by nightfall that the mountains became hillocks, and the plain was soaked with the blood of the mighty.”

However, following a period of bloody conquest, the borders of the Mongol Empire were finally solidified and their expansion was halted.

When Genghis Khan died in 1227, he left behind him a vast territory stretching from the Korean Peninsula to Poland, and from northern Russia to Afghanistan and parts of Persia, capturing the Silk Road almost in its entirety.

This was the first and the last time that almost the entire length of the route was in the single hands of an empire, which stretched for more than 4,350 miles (7,000 kilometers).

What followed was a period known in history as Pax Mongolica. Relative peace was established in Eurasia as a direct consequence of Mongol military and political dominance, which allowed for the trade route to regain the importance it had in its glory days.

This was the time of the third Silk Road, with the first one being during the Han dynasty and the second dating from the times of Tang Empire in the 7th century.

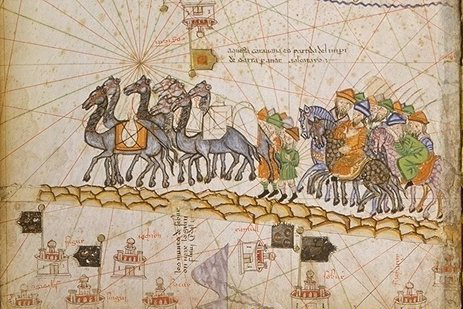

During the two prior periods, silk was the main export material ― hence the name ― but the Mongols brought in a number of other goods for which Europe craved.

Among them were pearls, gems, spices, precious metals, medicines, ceramics, carpets, numerous fabrics, and lacquerware.

Although trade was the main function of the Silk Road, it had a strong role in maintaining control over the vast Mongol Empire.

In order to keep the information flowing, alongside with merchandise, the Mongols built a great number of caravanserais ― sort of state-sponsored roadside inns ― together with post houses and bridges.

Since Mongol rule became law, the road became safe to travel. Trade flourished, filling up the treasuries of Genghis Khan’s heirs who divided the empire into four different khanates ― Yuan dynasty, Golden Horde, Chagatai Khanate and Ilkhanate.

Apparently, the route became so safe that one source claimed: “a maiden laden with gold could travel it and go unmolested.”

Trees were planted alongside many portions of the road in order to provide shade for the caravans.

This goes to show how prosperous it actually was ― given that comfort of the travelers wasn’t exactly a must-have in the times of Mongol reign.

While some cities, like Merv and many others, were burned to the ground, never to restore their former glory, cities like Samarkand in modern-day Uzbekistan were rebuilt, once again becoming trade capitals of their regions.

Besides from goods, money, and information that traveled alongside the Silk Road, an influx of curious Europeans rose as well ― in fact, the 14th century brought adventurers and chroniclers of the likes of Marco Polo to the very heart of the Mongol Empire.

Read another story from us: One of the Most Beautiful and Historic Falkland Islands is Now for Sale

The exchange which ensued together with trade created a completely new chapter in history ― one that would help different civilizations on the opposite sides of the Eurasian continent to finally introduce themselves through culture, rather than war.