There are movies that depict nightmare scenarios. Then there are movies where the making was a nightmare scenario.

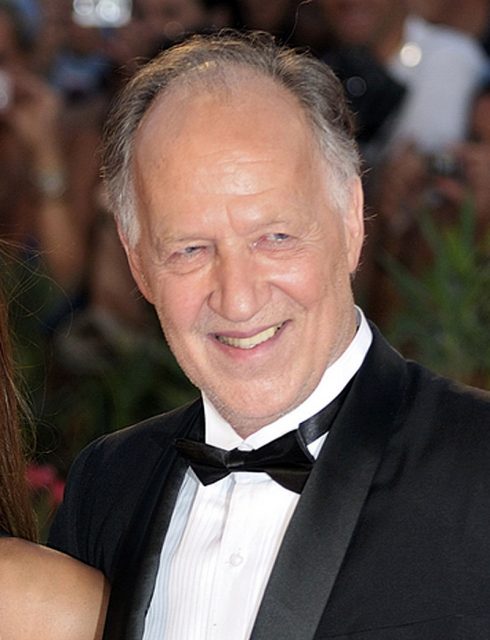

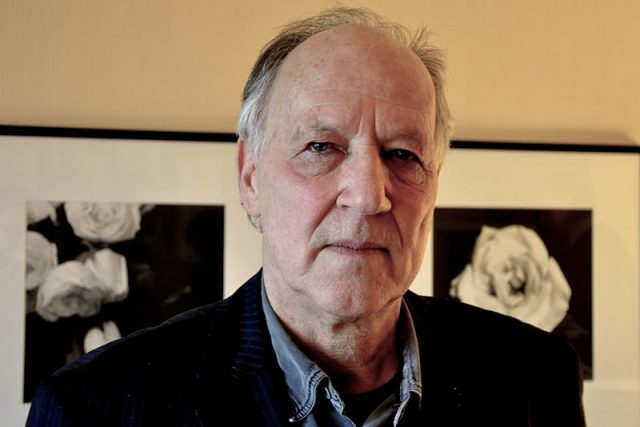

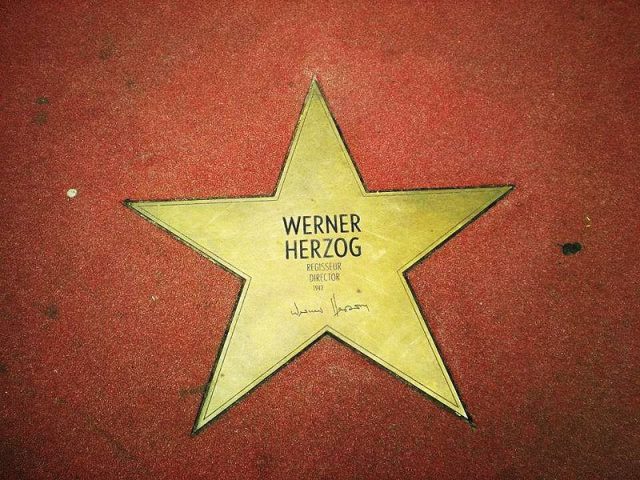

Every so often you get a legendary picture which achieves the dubious honor of both categories. One of these is Fitzcarraldo, director Werner Herzog’s period epic from 1982.

Set in the early 20th century, deep in the steamy environment of the Amazon Basin, it was inspired by the exploits of a Victorian gentleman named Jose Fermin Fitzcarrald.

According to a 2007 article in the Sunday Herald, he was a “rubber baron with a private army of 5,000 men and a territory the size of Belgium.”

As is the case with artistic inspiration, it took a small detail to plant the seed of an idea in Herzog’s mind. His “interest had been sparked by a chance detail that (Fitzcarrald) had once dismantled a boat, carried it overland from one river to the next and reassembled it to continue his exploration.”

When it came to realizing the story, Herzog didn’t do things by halves. For starters, he turned Fitzcarrald into Fitzcarraldo, an Irish opera buff whose rubbery adventures were in service of a wild dream where he builds an opera house in the jungle. Then he decided to avoid home comforts by shooting in the actual Peruvian location.

So far, so awkward. However there was greater ambition to come. For the 320-ton steamship in the script, which gets dragged up the side of a mountain, Herzog decided against using models. In fact he had 2 vessels to hand, anticipating that one might be destroyed during this Herculean effort.

The director was also thinking of Sisyphus, the figure from Greek mythology who famously had to push a giant boulder uphill over and over for all eternity. While the production of Fitzcarraldo was comparatively shorter, it lasted years rather than the usual matter of months.

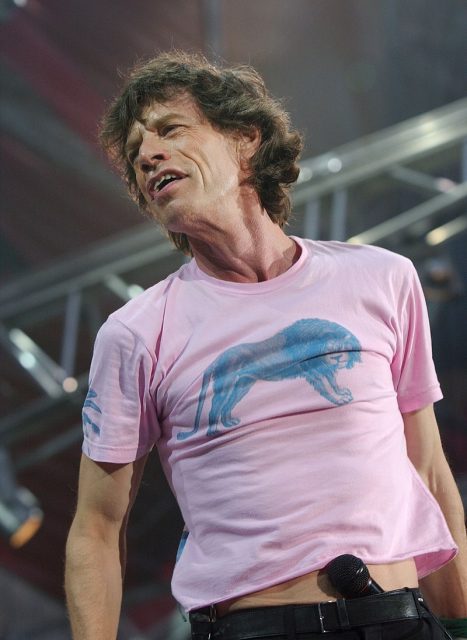

For the title role, Herzog chose Jason Robards, with Mick Jagger providing support as a mentally-challenged assistant. After several months of filming in tougher than tough conditions, Robards contracted amoebic dysentery and had to leave the movie.

Jagger then departed for a Rolling Stones tour, whereupon Herzog made the extraordinary move of removing his character from the action, such was the power of the rock star’s performance. Speaking in a 2001 interview, Herzog remarked: “Losing Mick was, I think, the biggest loss I have ever experienced as a film director…I liked him so much as a performer that any replacement would have been an embarrassment.”

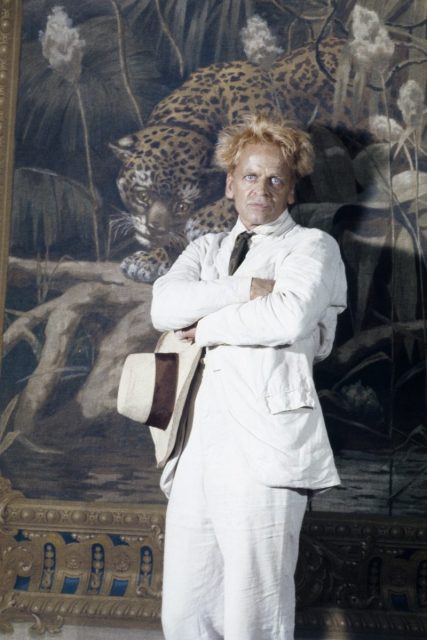

Starting from scratch with arguably the most complex film shoot of all time was a huge gamble. Robards was a fine actor, yet replacement Klaus Kinski inhabited the role in a way his predecessor never could.

As Roger Ebert observed in 2005, “Kinski was a better choice for the role than Robards, for the same reason a real boat was better than a model: Robards would have been playing a madman, but to see Kinski is to be convinced of his ruling angers and demons.”

Herzog had initially resisted casting friend and collaborator Kinski as Fitzcarraldo. To put it mildly, he figured the experience would not agree with his temperament. On top of that they were constantly rubbing each other up the wrong way. During a previous job on Aguirre: The Wrath of God (1972) – which also required jungle filming – Herzog had actually pointed a gun at Kinski.

Nevertheless, he took the plunge into uncharted waters with his unpredictable pal. The Sunday Herald comments that “For hundreds of native Indian extras already wary at being asked to help drag Herzog’s steamboat up a muddy slope, the daily outbursts of the raving white man were incomprehensible and terrifying. At one point a local chief approached the director and offered to have Kinski killed.”

Before the movie even got going, there was controversy over the use of indigenous peoples as participants. The concerns were misplaced but the hiring of tribesmen brought its own troubles. And not just trouble, but fully-fledged danger.

A brutal attack by the Amahuaca tribe saw an arrow pierce a man’s throat (he survived) and his wife needing an urgent operation after being “hit in the stomach, necessitating eight hours of emergency surgery on a kitchen table. ‘I assisted by illuminating her abdominal cavity with a torchlight,’ recalled Herzog, ‘and with my other hand sprayed with repellent the clouds of mosquitoes that swarmed around the blood.’”

The gruesome incidents piled up. At one point a logger took the drastic step of chainsawing his foot off to deal with a snake bite. And the production tragically played host to actual deaths, with extras falling prey to illness in the inhospitable conditions.

Such was the chaos that documentary Burden of Dreams, shot by Les Blank as the shoot was going on, became as well-known as the movie. Chronicling the shocking scale of the offscreen drama, it won a British Academy Award. As for Herzog, his vision was recognized with a Best Director gong at the Cannes Film Festival.

Was the project ultimately worthwhile? That question may have haunted the director but as he passionately explained to his investors, quoted in the Herald, “I live my life or I end my life with this project!”

Read another story from us: The Master of Suspense – 5 Revealing Facts of Alfred Hitchcock

For critics like the great Roger Ebert, the making of Fitzcarraldo and the end product are part of the same convention-shattering entity. In what is perhaps the definitive word on the subject, he described the film as “one of the great visions of the cinema, and one of the great follies. One would not have been possible without the other.”