The Victorian Age was generally thought of as a strict, uptight time when morals mattered and the slightest infraction of social etiquette would send fingers (and tongues) wagging. In theory, anyway.

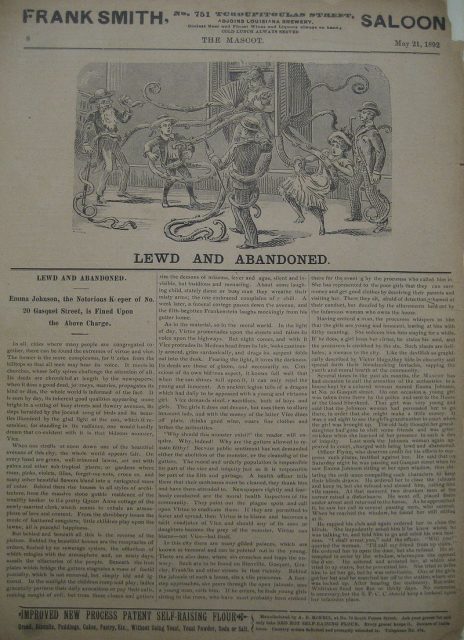

Fact is, the world’s oldest profession was going strong in this stodgy era — in private and sometimes in public.

All any man had to do was peruse a statewide directory — the Travelers’ Guide of Colorado, for one — to figure out which house of ill repute was the right fit for him. (“Twenty young ladies engaged nightly to entertain guests,” read one entry.)

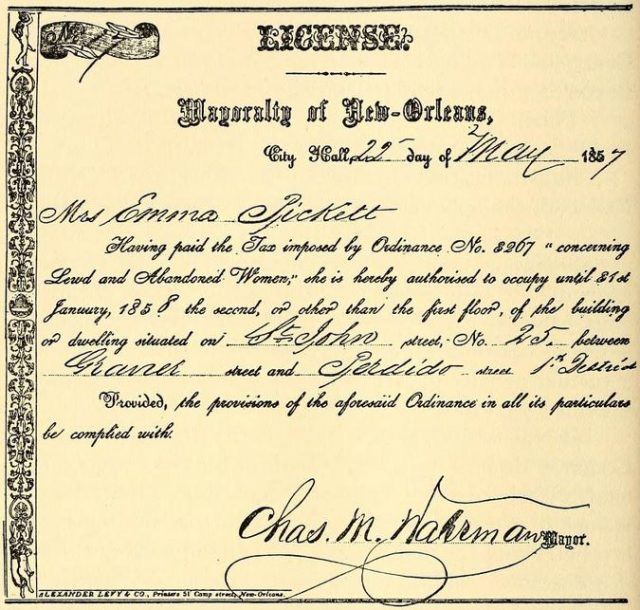

Heck, in New Orleans, brothels were almost encouraged, which did not amuse the puritanical types of the day. “The extent of prostitution is without a parallel in the civilized world,” tsk-tsked one editorial. “Men seldom seek to go in disguise.”

Indeed, prostitution was considered a “necessary evil” that helped keep marriages together, since men could satisfy their sexual desires when their partners weren’t up to performing for whatever reason. Besides, prostitution wasn’t a crime in the early part of the 19th century. Even brothels were accepted, with law officials for the most part turning a blind eye.

The ages of these working girls ranged from 13 to 50, with 21 being the average age. And though brothels, or bawdy houses as they were also known, were a way for poor women to make a buck, they also attracted creative types (trained musicians, for example), and ordinary housewives looking to trade their hum-drum lives for a little kick-up-your-heels fun.

By the 1830s, prostitution became increasingly visible. With the establishment of police forces, conspicuous streetwalkers were occasionally rounded up, but raids on brothels rarely happened. And make no mistake, there was a smorgasbord of bordellos to choose from, particularly in the cities up north.

Early in the 19th century, the major vice district in New York was “Hell’s Hundred Acres” (now artsy SoHo).

But as the city grew northward, businesses followed — even the shady kind. In 19th century New York City, particularly between 1850 and 1910, a good time wasn’t hard to find it.

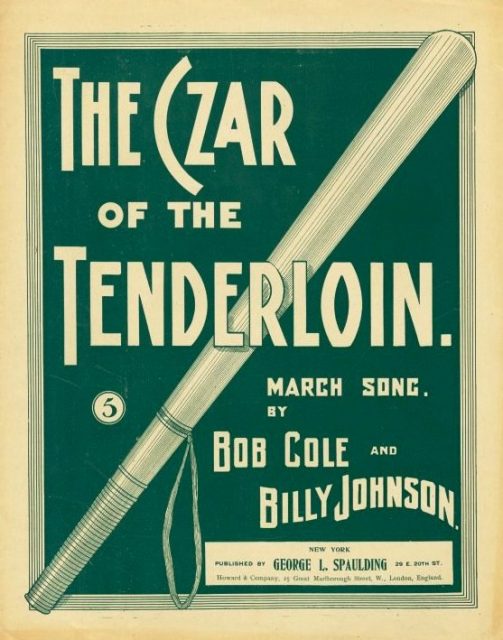

The Tenderloin was the most famous red-light district in Manhattan — situated between well-heeled Gramercy Park and Murray Hill on the east and working-class Hell’s Kitchen on the west, and extending north from 23rd Street.

By the 1880s, one could find a staggering number of nightclubs, saloons, bordellos, gambling houses, and dance halls. One guesstimate had (at least) half of the buildings in the district connected with some kind of scandalous goings-on.

New York City Police Department Captain Alexander S. “Clubber” Williams gave the area its moniker in 1876, when he was transferred to a precinct in the middle of the district.

Citing the number of bribes he was pocketing for protection of the illegitimate businesses on his turf — especially the brothels — Williams famously said, “I’ve been having chuck steak ever since I’ve been on the force, and now I’m going to have a bit of tenderloin.”

Reformers, however, had another name for the area: “Satan’s Circus.” One minister, the Rev. Thomas De Witt Talmage, called New York City “the modern Gomorrah” for allowing such sacrilege to exist.

The Tenderloin bordellos were smack dab in the middle of some of Manhattan’s prime real estate: just a stone’s throw from Broadway, the Metropolitan Opera house, Carnegie Hall, and the Waldorf Astoria.

Not surprisingly, the clientele wasn’t comprised solely of working-class stiffs — even upper-crust types liked to get down-and-dirty every once in a while. One group of enterprising sisters (seven of them, to be exact) presided over a row of brothels in a residential neighborhood on West 25th Street, luring customers — who were sometimes required to wear formal attire — with fancy engraved invites.

The girls that worked in these houses (“cultured and pleasing companions” promised ads that ran in the daily newspapers) were surprisingly sophisticated, and not only in matters of the boudoir. (They were also generous: On Christmas Eve, a certain percentage of the profits were donated to charities.)

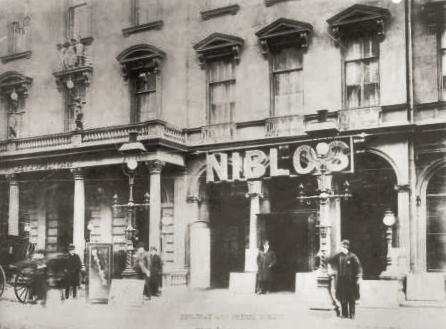

There were other establishments for those looking for a little action. Koster and Bial’s Music Hall was a rowdy saloon where customers could knock back whiskey while watching can-can girls.

At Haymarket, men could actually dance with the strumpets, then whisk them off behind a curtain for some funny business.

Wives, no doubt, weren’t exactly thrilled with the goings-on of their men, but because of their lowly status, there wasn’t much they could do about the extracurricular activities.

One street, in particular, had created quite a buzz: “Soubrette Row” (soubrette being a French word for “lively, flirtatious girl”), just spitting distance from the then-new Metropolitan Opera House — an ideal locale for those looking for a little action after other more “acceptable” entertainment.

At these fancier bordellos, run by French madams, all sorts of activities were allowed — some so outrageous that even other girls in The Business were scandalized. If a man had the means, he could satisfy pretty much any urging. By 1890s, Soubrette Row was known around the country as the place for risqué pleasures.

Read another story from us: The 7 Worst Pieces of Sex Advice Dispensed Throughout History

Alas, the good times ultimately came to an end. In the early 1900s, the Progressive Era ushered in more conservative views when it came to vice. A movement was underway — led, in part, by the Protestant middle class, as well as the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (the same killjoys who played a role in the prohibition of alcohol) — to criminalize and stamp out prostitution. Between 1910 and 1915, prostitution was made illegal in almost all states.