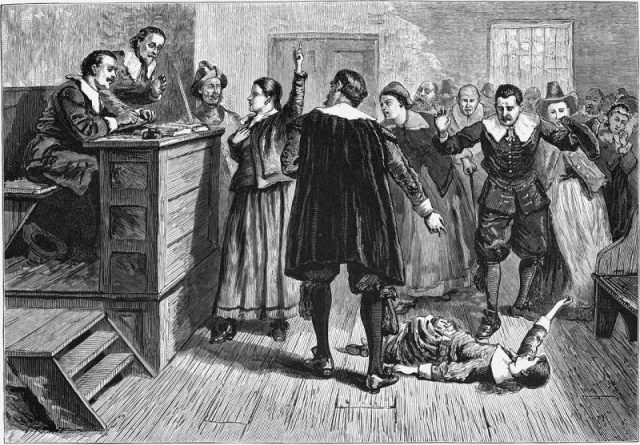

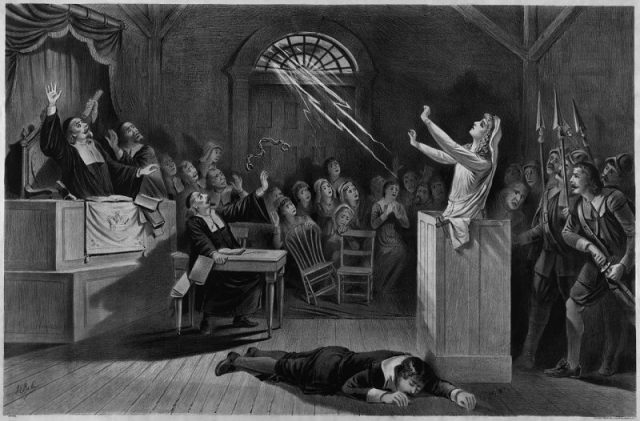

Impassioned figure-pointing, stunning accusations, torrents of tears, out-of-control hysteria.

People in Salem, Massachusetts, as well as across the pond, were blamed for all sorts of malevolent misconduct back in the day.

Were they lackeys of Lucifer or innocent victims? Get a load of these trumped-up tests employed to suss out supernatural mischief.

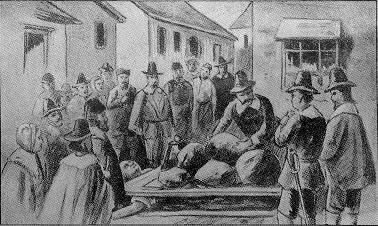

Swimming Test

One might say, water was not a witch’s friend. Suspected devil worshipers were stripped of their undergarments, hog-tied at their hands and feet, then tossed into a lake or pond to see if they would sink or float.

Witches were believed to have rebuffed the Christian sacrament of baptism, so it was thought that water would “reject” them, forcing them to float to the surface like an inflatable pool toy — whereas, the innocent would sink helplessly to the depths below.

Sometimes a rope was tied around the accused’s neck to hoist them to the surface once they started to sink, but some unfortunate souls drowned nonetheless.

Put to the test: In 1613. Mary Sutton and her mother were suspected of causing the servant of a landowner to fall into a coma, and then, when the landowner’s surly son threw stones at one of them, cast a spell that caused him to fall ill and kick the bucket.

That cinched it: Sutton’s hands and feet were bound together, then with men on either side of the pond holding opposite ends of the rope, she was tossed into the muck.

But it’s hard to keep a good woman down. Sutton returned to the surface and upon recovering consciousness she once again denied all charges.

It was all for naught. Sutton’s young son, for whatever reason, accused his mom of being witch. Sutton, her spirit broken, confessed to all charge, as did her mother. Both were formally accused of witchcraft and hanged as witches.

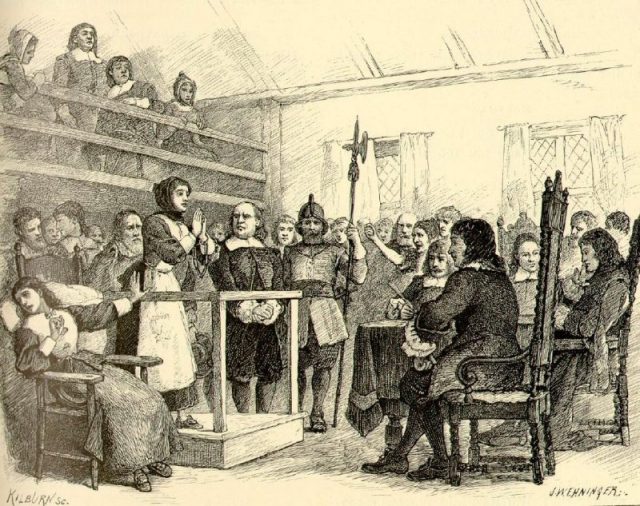

Prayer Test

Talk about performance anxiety. It was believed that witches were unable to recite the words of the scripture aloud, so the accused were told to quote parts of the Bible — the Lord’s Prayer was a particular favorite.

Any errors (no do-overs here!) were a sign of colluding with the Antichrist.

Put to the test: Jane Wenham, accused of being a witch 1712, didn’t exactly ace her audition — stumbling over the phrases “forgive us our trespasses” and “lead us not into temptation” during her recitation — and was dragged into court.

The jury was mesmerized, but the judge, Sir John Powell at the Assize Court at Hertford, wasn’t quite buying the whole witch thing. (When an accusation of flying was made, he noted, tongue firmly in cheek, that there was no law against it.) Though Wenham would be found guilty, Powell set aside her conviction, suspending the death penalty. Still, even a kick-ass performance didn’t mean an accused witch was off the hook.

During the Salem Witch Trials, George Burroughs recited the prayer — flawlessly — from the gallows just before The Big Drop. Alas, his performance was dismissed as a bit of devilish trickery, and the hanging proceeded as planned.

Touch Test

The premise here: Victims of sorcery were believed to react strangely when touched by their tormentor — so when a possessed person went into one of their frenzies, the suspected witch would be instructed to a lay a hand on them.

If the girl didn’t react, all was good; but if she became calm, it was proof that the suspect had placed them under a spell. That’s because the evil that seeped into the victim’s soul had returned to that from which they came.

Put to the test: In 1662, two elderly English women, Rose Cullender and Amy Denny, were charged with bedeviling a pair of girls, who responded by clenching their fists so tightly during seizures, their digits couldn’t be pried apart. But wouldn’t you know it: Whenever either of the older women touched the girls, their hands sprang open.

Not so fast, said the court. To be sure they weren’t being bamboozled, the girls were blindfolded and touched by other members of the court. The girls unclenched their fists again — proof positive that they were indeed faking. Even so, this wasn’t enough to save the necks of Cullender and Denny, who were hung as witches.

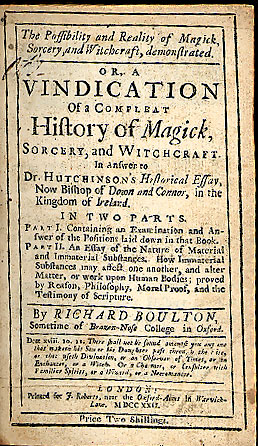

Witch Cakes

Sure, it sounds like something from an episode of The Food Network’s “Halloween Wars.” But witch cake was actually a confection whipped up to suss out Satan followers. The recipe was pretty simple: Take a sample of the victim’s urine, some rye-meal, a sprinkle of ashes, mix them all together, and bake.

The finished dish was fed to a dog (pooches were thought to be the canine cohorts of witches). If the pup fell under its spell and exhibited the same symptoms as the victim (say, biting or barking at the moon), inappropriate hocus-pocus was proven.

Put to the test: In an infamous incident from 1692 Salem, Massachusetts, two girls, Elizabeth Parris and Abigail Williams, began displaying puzzling behavior — contorting their bodies into odd shapes, constantly complaining of fever.

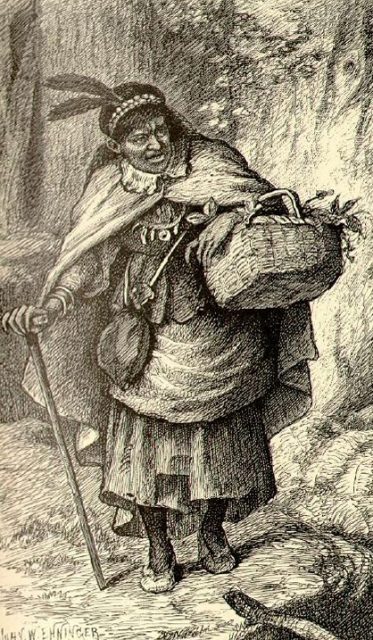

A know-it-all neighbor of the Parris family, Mary Sibley, suggested the making of a cake to reveal whether witchcraft was involved. Tituba, a slave in the Parris household, whipped up the dastardly dessert and fed it to the family dog.

The concoction failed to work and Tituba was admonished for her attempted use of sorcery. Things got worse: Tituba’s supposed knowledge of spells was used as evidence against her by the two girls. Though Tituba swore she wasn’t a witch, she admitted that she made the witch cake to help Elizabeth Parris. She was ultimately found not guilty due to a lack of evidence.

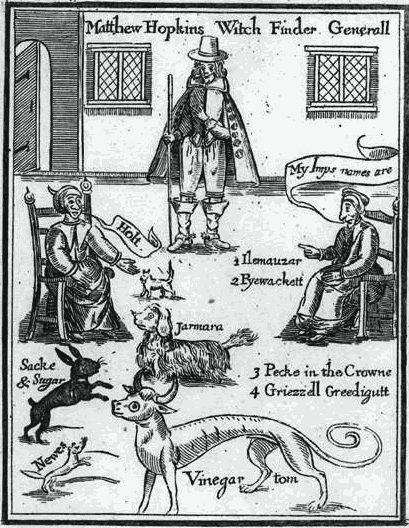

Pricking and Scratching

Witch’s marks were believed to be the permanent marking of the Devil on his disciples to seal their loyalty. Moles, scars, birthmarks, sores, supernumerary nipples, and pretty much any skin condition that would send you to a dermatologist, fit the bill.

Another damning imperfection: a “witches’ teat” (believed to be an extra nipple allegedly used to suckle the witch’s “helper” animals, but probably more of a wart). The accused were stripped — sometimes their body hair was shaved to make sure nothing could be concealed — and publicly examined.

Terrified villagers would sometimes attempt to cut off or burn any suspicious marks, only to have their wounds pointed to as proof of a pact with the Prince of Darkness.

But even if the accused’s skin was blemish-free, they weren’t off the hook. It was thought that a witch could be discovered by being pricked with needles, pins, and bodkins (sharp instruments used to punch holes in cloth), until an insensitive area was found. If the recipient didn’t bleed or feel pain, she was a “cold and insensitive” witch. The suspect might also be subjected to scratching by their so-called victims.

Supposedly, the “possessed” found relief for their unexplained ailments by scratching the person responsible, until they drew blood. If their symptoms improved after digging in, it was seen as proof of guilt.

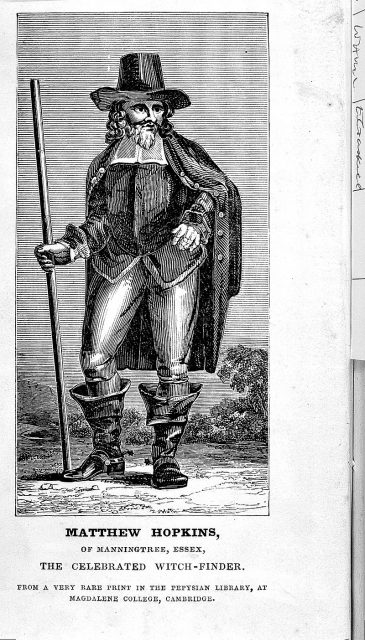

Put to the test: In Europe, so-called “witch-finders” (i.e. professional prickers) were hired to help find witches. One Brit, Matthew Hopkins, was actually given the moniker “Witch Finder General.” Seriously. These men would travel from town to town, and were paid a tidy sum for their services.

Not surprisingly, most were con artists who used sleight of hand to expose witchery. Some carried hollow wooden handles and retractable points, which would give the appearance of an accused witch’s flesh being penetrated without leaving a mark, nor causing bleeding or pain. Others wielded specially designed needles — sharp on one end, blunted on the other. Employing some sneaky manual dexterity, the pricker would use the sharp end to poke certain parts of the body, causing pain, then secretly switch to the blunt end, and have a go at the alleged witch’s mark.

Related Video: 13 Victorian Vulgarities everyone should know:

https://youtu.be/utw0IVJcGK0

Incantations

Another lose-lose proposition. This test involved forcing the accused witch to verbally order the devil to let the possessed victim come out of their fit or trance. If the victim’s condition improved, the supposed tormentor was toast.

Put to the test: When 76-year-old Alice Samuels and her family were fingered for being behind fits afflicting Jane Throckmoroton and her four sisters, judges forced the elderly woman to demand that the devil release the Jane from her torture by announcing, “As I am a witch…so I charge the devil to let Mistress Throckmorton come out of her fit at this present.”

Read another story from us: House of Salem Man Hanged for Witchcraft Goes On Sale

When the possessed girl immediately snapped out of her suffering, Samuels, along with her daughter and husband, were found guilty and strung up as witches.