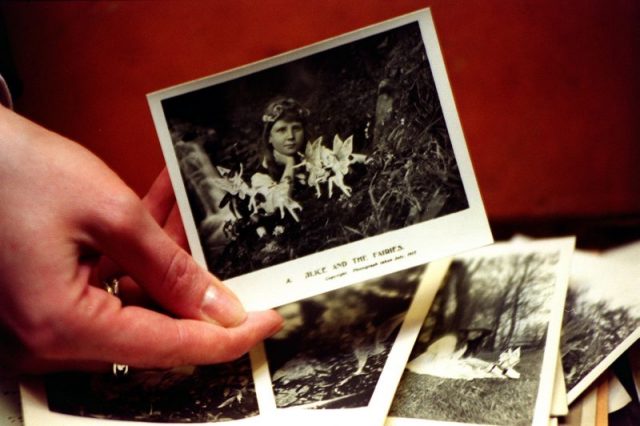

Prints of the famous Cottingley fairy photographs recently came to auction. Although initially expected to fetch £2,000 ($2,600), they ended up selling for over £20,000 ($26,000).

The photographs have been famous ever since they were published in the 1920 Christmas edition of The Strand.

The world was aghast to see pictures, taken by two young girls, apparently proving the existence of fairies.

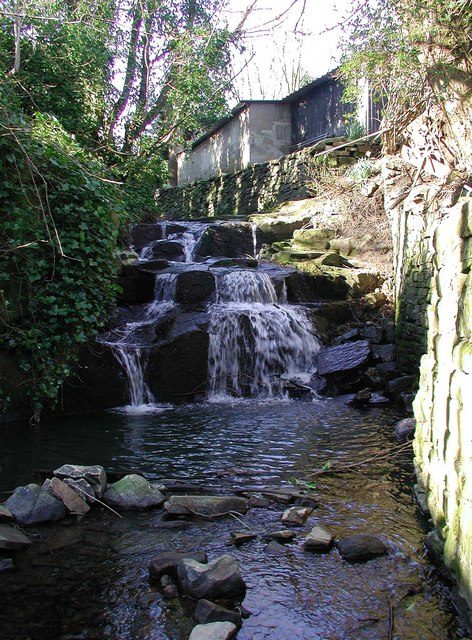

Elsie Wright, aged 16, and nine-year-old Frances Griffiths were cousins. When they took the first photographs, Frances was visiting Elsie, who lived in the village of Cottingley, England.

The girls used to play a lot by a nearby stream. This annoyed Elsie’s mother since they often came back bedraggled, but the girls insisted they went there to see the fairies.

When no one believed the cousins, Elsie took her father’s camera the next time they went to play. When they came back, Elsie’s father, Arthur, developed the photographs they’d taken.

Among them was one showing Frances sitting with four fairies dancing in on a rock in front of her.

Arthur knew his daughter was creative and assumed the fairies were merely cardboard cut-outs. But two months later, the girls took another photograph which Elsie’s mother, Polly, was convinced was authentic.

In mid-1919, Polly attended a meeting of the Theosophical Society in Bradford. The subject under discussion was “fairies,” so she took the pictures along.

The photographs were subsequently exhibited at the Society’s annual conference, and so they came to the attention of the public.

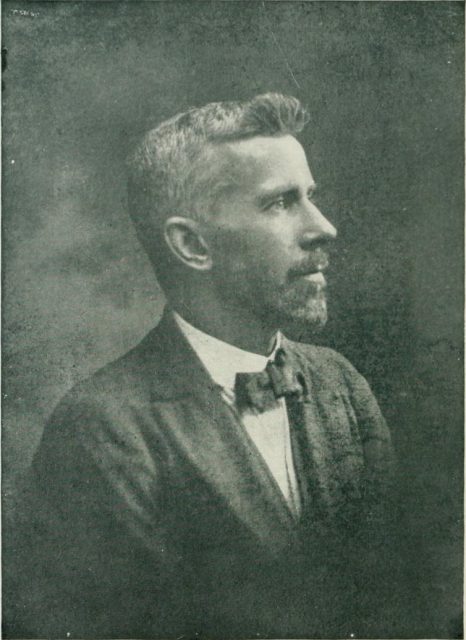

Edward Gardner was a leading member of the Society. He sent the prints, along with the original glass-plate negatives, to Harold Snelling, a photography expert.

Snelling’s response was that “the two negatives are entirely genuine, unfaked photographs… [with] no trace whatsoever of studio work involving card or paper models.”

However, Snelling made it clear that he wasn’t suggesting that the photographs proved the existence of fairies, only that they hadn’t been tampered with, but showed “whatever was in front of the camera at the time.”

Gardner got Snelling to make prints, which he took with him to lectures he gave around the country.

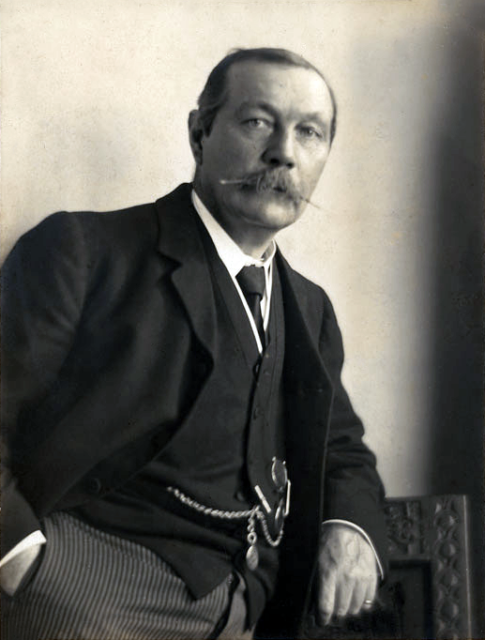

The pictures ultimately came to the attention of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, a prominent spiritualist as well as the author of the Sherlock Holmes stories.

Doyle and Gardner had the photographs examined by two more experts. After three evaluations, it seemed that only one came back with the opinion that there was “some evidence of faking.”

Gardner went to visit Elsie and her family. Arthur Wright said that he’d been so sure the photographs were fake that he’d searched Elsie’s room and the stream in an effort to find evidence. But he’d failed to find anything incriminating.

Gardner wanted to prove the photographs beyond doubt. To that end, Frances was invited to stay with the Wrights again for the summer of 1920.

At the end of July, Gardner returned with two Kodak cameras and 24 photographic plates.

He gave each girl a camera and some brief instructions on how to get the best pictures. However, he assured them “[i]f nothing came of it at all… they were not to mind a bit.” He did not want them to feel under pressure.

The girls insisted that the fairies would not come if others were watching, so they were left alone.

They took several pictures over that time, including those entitled Fairy offering Posy of Harebells to Elsie, Frances and the Leaping Fairy, and Fairies and their Sun-Bath.

Doyle sought permission from Arthur Wright to publish the first two pictures as part of his article on fairies which he was writing for The Strand. Arthur gave his consent. Doyle protected their identity by naming the family as “the Carpenters” in his article.

The photographs had a mixed reception. Maurice Hewlett, a historical novelist and poet, stated in an article for John O’London’s Weekly: “knowing children, and knowing that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle has legs, I decide that the Miss Carpenters have pulled one of them.”

In 1921, Doyle published the later pictures in The Strand, inspiring similar reactions. In August of that year, Gardner took another trip to Cottingley.

This time, Gardner took with him Geoffrey Hudson, a noted clairvoyant. Neither Elsie nor Frances claimed to see any fairies during that visit. In contrast, Hudson claimed he saw them everywhere.

After 1921, interest in the photographs died down. In 1966, Elsie was interviewed by a reporter from The Daily Express. She didn’t say the photographs were fake but suggested that what the camera had succeeded in photographing might have been a figment of her imagination. She gave the same story again in another interview in 1971.

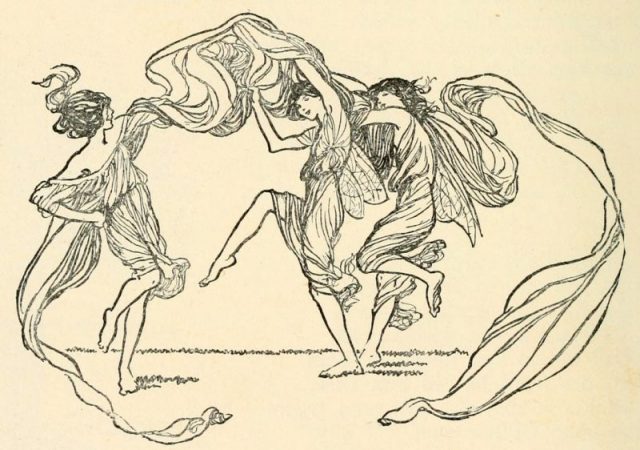

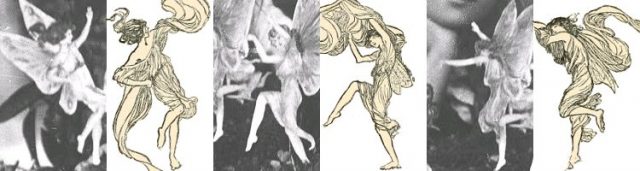

Finally, in 1983, the cousins admitted that the pictures were fake. Elsie had copied pictures of dancing girls from Princess Mary’s Gift Book and drawn wings on them. The two girls had then cut the drawings out and stood them upright using hatpins, which they later disposed of in the stream.

However, the girls disagreed on the authenticity of the fifth photograph, the last one they took. Elsie maintained it was a fake, but Frances said: “It was a wet Saturday afternoon and we were just mooching about with our cameras and Elsie had nothing prepared. I saw these fairies building up in the grasses and just aimed the camera and took a photograph.”

Geoffrey Crawley, in a letter to The Times published in April 1983, suggested how both girls might be telling the truth. He reasoned that the photograph was “an unintended double exposure of fairy cutouts in the grass.”

In 1985, for the television program Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers, Elsie admitted why they had carried on the ruse for so long: they were embarrassed to admit the truth after fooling the famous author.

“Two village kids and a brilliant man like Conan Doyle – well, we could only keep quiet… I never even thought of it as being a fraud – it was just Elsie and I having a bit of fun and I can’t understand to this day why they were taken in.”

Geoffrey Crawley sold his Cottingley fairy collection to the National Science and Media Museum in Bradford. The items included prints of the photographs, two of the cameras used, watercolors painted by Elsie, and a letter admitting to the hoax written by Elsie.

On October 4, 2018, two of the prints used by Gardner in his lectures came under the hammer at Dominic Winter Auctioneers in Cirencester, England. Since these were only prints, rather than the original photographs, they were given a conservative estimate of £700-£1,000 ($900-$1,300) each.

In fact, the print of Elsie with a gnome sold for £5,400 (around $7,000) while the other print, showing Frances with the fairies sold for £15,000, or almost $20,000.

Read another story from us: Marie Antoinette’s Dazzling Jewelry Made Public for the First Time Ever

With such a price tag, it seems fair to say that the Cottingley photos fascinate the public as much today as they did in 1920.